JF Ptak Science Books LLC Post 266

There are no doubt many instance of voluntary crucifixtion by religious zealots--the case of Matthew Lovat, seen here in an issue of the compact London-based polite journal called The Mirrour (of Literature, Amusement and Instruction) is particularly pungent because he figured out a way to crucify himself without the help of others. If you allow yourself to think about this a bit--and I must admit, the thought of self- and un-aided crucifixion had never entered my head before now--it really is a difficult procedure to implement. Mr. Lovat seems to have thought it out and conquered the lowly demons that stood between him and him cross. I've reprinted some of the explanation of how he undertook this adventure in 1802, included in the continued reading section below.

I should quickly point out that Lovat, a shoemaker from Italy ("born of poor parents, employed in the coarsest and most laborious works of husbandry, and fixed to a place remote from almost all society"), survived himself and after having his health restored escaped into the city wearing nothing but a shirt. He was brought back into custody ("by the servants") and remanded to the Lunatic Asylum of San Servolo, in Venice. This was no doubt an unhappy situation, for anyone, crazy or not. Lovat expired himself finally in 1808, evidently from taking too much sun.

The Matthew Lovat Saga, from The Mirrour, Saturday, 7 December, 1822 (later two-thirds of the story):

"Until the month of July, 1802, Matthew Lovat did nothing extraordinary. His life was regular and uniform, his habits were sample, and nothing distinguished him, but an extreme degree of devotion. He spoke on no other subject than the affairs of the church. Its festivals and fasts, with sermons, saints, &c. constituted the topics of his conversation. It was at this date, that, in imitation of the early devotees, he determined to disarm the tempter, by mutilating himself. He effected his purpose without having anticipated the species of celebrity which the operation was to procure for him; and which compelled the poor creature to keep himself shut up in his house, from which he did not venture to stir for some time, not even to go to mass. At length, on the 13th of November, in the same year, he went to Venice, where a younger brother, named Angelo, conducted Matthew to the house of a widow, the relict of Andrew Osgualda, with whom he lodged, until the 21st of September in the following year, working assiduously at his trade, and without exhibiting any signs of madness. But on the above-mentioned day, he made an attempt to crucify himself, in the middle of the street called the Cross of Biri, upon a frame which he had constructed of the timber of his bed: he was prevented from accomplishing his purpose by several people, who came upon him just as he was driving the nail into his left foot. His landlady dismissed him from her house, lest he should perform a similar exploit there. Being interrogated repeatedly as to the motive for his self-crucifixion, he maintained an obstinate silence, except that he once said to his brother, that that day was the festival of St. Matthew, and that he could give no farther explanation. Some days after this affair, he set out for his own country, where he remained a certain time, but afterwards returned to Venice, and in July, 1805, lodged in a room in the third floor of a house, in the street Delle Monache.

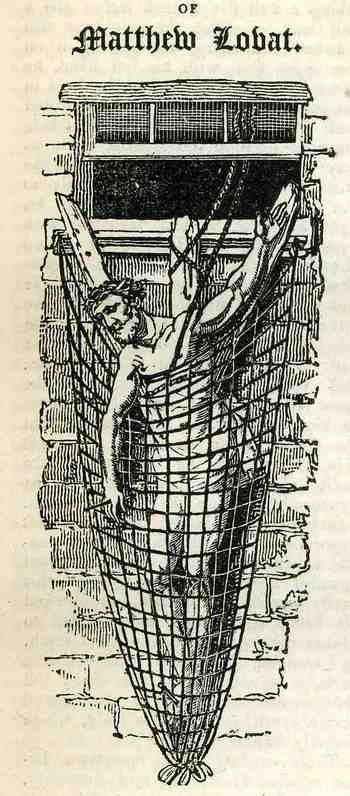

Here his old ideas of crucifixion laid hold of him again. He wrought a little every day in forming the instrument of his torture, and provided himself with the necessary articles of nails, ropes, bands, the crown of thorns, &c. As he foresaw that it would be extremely difficult to fasten himself securely upon the cross, he made a net of small cords capable of supporting his weight, in case he should happen to disengage himself from it. This net he secured at the bottom, by fastening it in a knot at the lower extremity of the perpendicular beam, a little below the bracket designed to support his feet, and the other end was stretched to the extremities of the transverse spar, which formed the arms of the cross, so that it had the appearance in front of a purse turned upside down. From the middle of the upper extremity of the net, thus placed, proceeded one rope; and from the point at which the two spars forming the cross intersected each other, a second rope proceeded, both of which were firmly tied to a beam in the inside of the chamber, immediately above the window, of which the parapet was very low; and the length of these ropes was just sufficient to allow the cross to rest horizontally upon the floor of the apartment.

These cruel preparations being ended, Matthew stripped himself naked, and proceeded to crown himself with thorns; of which two or three pierced the skin which covers the forehead. He next bound a white handkerchief round his loins and thighs, leaving the rest of his body bare; then, passing his legs between the net and the cross, seating himself upon it, he took one of the nails destined for his hands, of which the point was smooth and sharp, and introducing it into the palm of the left, he drove it, by striking its head on the floor, until the half of it had appeared through the back of the hand. He now adjusted his feet to the bracket which had been prepared to receive them, the right over the left; and taking a nail five French inches and a half long, of which the point was also polished and sharp, and placing it on the upper foot with his left hand, he drove it with a mallet which he held in his right, until it not only penetrated both his feet, but entering the hole prepared for it in the bracket, made its way so far through the tree of the cross as to fasten the victim firmly to it. He planted the third nail in his right hand as he had managed with regard to the left, and having bound himself by the middle to the perpendicular of the cross by a cord, which he had previously stretched under him, he set about inflicting the wound in the, side with a cobler's knife, which he had placed by him for this operation, and which he said represented the spear of the passion. It did not occur to him, however, at the moment, that the wound ought to be in the right side, and not in the left, and in the cavity of the breast, and not of the hypocondre, where he struck himself transversely two inches below the left hypocondre, towards the internal angle of the abdominal cavity, without however injuring the parts which this cavity contains. Whether fear checked his hand, or whether he intended to plunge the instrument to a great depth, by avoiding the hard and resisting parts, it is not easy to determine; but there were observed near the wound several scratches across his body, which scarcely divided the skin.

These extraordinary operations being concluded, it was now necessary, in order to complete the execution of the whole plan which he had conceived, that Matthew should exhibit himself upon the cross to the eyes of the public; and he realized this part of it in the following way. The cross was laid horizontally on the floor, its lower extremity resting upon the parapet of the window, which was very low, then raising himself up by pressing upon the points of his fingers (for the nails did not allow him to use his whole hand either open or closed), he made several springs forward, until the portion of the cross which was protruded over the parapet, overbalancing what was within the chamber, the whole frame, with Matthew upon it, darted out at the window, and remained suspended outside of the house by the ropes which were secured to the beam in the inside. In this predicament, the poor fanatic stretched his hands to the extremities of the transverse beam which formed the arms of the cross, to insert the nails into the holes which had been prepared for them: but whether it was out of his power to fix both, or whether he was obliged to use the right on some concluding operation, the fact is, that when he was seen by the people who passed in the street, he was suspended under the window, with only his left hand nailed to the cross, while his right hung parallel to his body, on the outside of the net. It was then eight o'clock in the morning. As soon as he was perceived, some humane people ran up stairs, disengaged him from the cross, and put him to bed. A surgeon of the neighbourhood was called, who made them plunge his feet into water, introduced tow by way of caddis into the wound of the hypocondre, which he assured them did not penetrate into the cavity, and after having prescribed some cordial, instantly took his departure.

At this moment, Dr Ruggieri, professor of Clinical surgery, hearing

what had taken place, instantly repaired to the lodging of Lovat, to

witness with his own eyes a fact which appeared to exceed all belief.

When he arrived there, accompanied by the surgeon Paganoni, Matthew's

feet, from which there had issued but a small quantity of blood, were

still in the water—his eyes were shut—he made no reply to the questions

which were addressed to him; his pulse was convulsive, and respiration

had become difficult. With the permission of the Director of Police,

who had come to take cognizance of what had happened, Dr. Huggieri

caused the patient to be conveyed by water to the Imperial Clinical

School, established at the Hospital of St. Luke and St. John. During

the passage, the only thing he said was to his brother Angelo, who

accompanied him in the boat, and was lamenting his extravagance: which

was, "Alas, I am very unfortunate.” At the hospital, an examination of

his wounds took place; and it was ascertained that the nails had

entered by the palm of the hands, and gone out at the back, making

their way between the bones of the Metacarpus, without inflicting any

injury upon them: that the nail which wounded the feet had entered

first the right foot, between the second and third bones of the

Metatarsus towards their posterior extremity; and then the left,

between the first and second of the same bones, the latter of which it

had laid bare and grazed: and lastly, that the wound of the hypocondre

penetrated to the point of the cavity. The patient was placed in an

easy position. He was tranquil and docile: the wounds in the

extremities were treated with emollients and sedatives. On the fifth

day, they suppurated with a slight redness in their circumference; and

on the eighth, that of the hypocondre was perfectly healed.

The

patient never spoke. Always sombre and shut up in himself, his eyes

were almost constantly closed. Interrogated several times, relative to

the motive which had induced him to crucify himself, he always made

this answer: "The pride of man must be mortified, it must expire on the

cross." Dr. Ruggieri, thinking that he might be restrained by the

presence of his pupils, returned repeatedly to the subject when with

him alone, and he always answered in the same terms. He was, in fact,

so deeply persuaded that the supreme will had imposed upon him the

obligation of dying upon the cross, that he wished to inform the

Tribunal of Justice of the destiny which it behoved him to fulfil, with

the view of preventing all suspicion that his death might have been the

work of any other hand than his own, With this in prospect, and long

before his martyrdom, he committed his ideas to paper, in a style and

character such as would be expected from his education, and the

disorder of his mind.

Scarcely was he able to support in his hand the weight of a book, when he took the prayer-book, and read it all day long. On the first days of August, all his wounds were completely cured; and as he felt no pain or difficulty in moving his hands and feet, he expressed a wish to go out of the hospital, that he might not, as he said, eat the bread of idleness. This request being denied to him, he passed a whole day without taking any food; and finding that his clothes were kept from him, he set out one afternoon in his shirt, but was soon brought back by the servants. The board of Police gave orders that he should be conveyed to the Lunatic Asylum, established at St. Servolo, where he was placed on the 20th of August, 1805,

After the first eight days he became taciturn, and refused every species of meat and drink. It was impossible to make him swallow even a drop of water during six successive days. Towards the morning of the seventh day, being importuned by another madman, he consented to take a little nourishment. He continued to eat about fifteen days, and then resumed his fast, which he prolonged during eleven.

These fasts were repeated, and of longer or shorter duration; the most protracted, however, not exceeding twelve days.

In January, 1808, there appeared in him some symptoms of consumption;

and he would remain immovable, exposed to the whole heat of the sun

until the skin of his face began to peel off, and it was necessary to

employ force to drag him into the shade.

In April, exhaustion proceeded rapidly, labouring in his breast was

observed, the pulse was very slow, and on the morning of the eighth he

expired after a short struggle.

"introduced tow by way of caddis into the wound" -- a standard procedure, I'm sure, but even with the Oxford English Dictionary, I'm not sure how to understand it. Tow and caddis are each used in various related ways relating to fibrous materials including flax, hemp, cotton, wool, and silk (if I remember correctly between the reference room and my office). The Scots (that inscrutable pale white horde) used caddis to refer to a lint used in surgery. I seem to recall a recent episode in Australia involving a man who invented a machine for shooting himself. Not as fascinating as self-crucifixion, by any stretch, but in the class of repelling yet compelling human endeavors.

Posted by: Jeff | 17 September 2008 at 11:09 PM