JF Ptak Science Books Post #80

Today’s post comes via my wife Patti’s phoney baloney sandwich for our four-year-old Tessie. It was a tight fit of geometric pieces made to cover slim pieces of bread that would fit into her bento boxes. The form was lovely! And—on the heels of yesterday’s post—it reminded me of the remarkable qualities of geometry, and the role it has played in the creation of the known and visible parameters of our world(s). Geometry has also played a very visible role in removing those parameters, for as much as the art has forced regularity in our thought, it has played just as large a role in challenging that structure. What Euclid has given, Lobachevsky has both taken away (and added to). (Nikolai Lobachevsky [1792-1867] and Janos Boylai [1802-1860] each independently developed non-Euclidean geometries: that is, they replaced Euclid's parallel postulate with the postulate that there is more than one parallel line through any given point, saying that the foundational fifth postulate of Euclid was not true.)

Take for example an image and idea from yesterday’s post regarding the engineer and art-geometer Oliver Byrne (who replaced much of the text of Euclid’s first six books by using an odd index of color) and Piet Mondrian. The approach (as noted by Augustus de Morgan among others) is gorgeous but hokum—the effect though is pretty and it does define the areas of the geometric solids that I’d like to use here. The approach that Byrne tried to develop and simplify Euclid for more general readers was to employ a peculiar art form of geometry to help classify the structure of the world—ordering the universe, and vice versa.

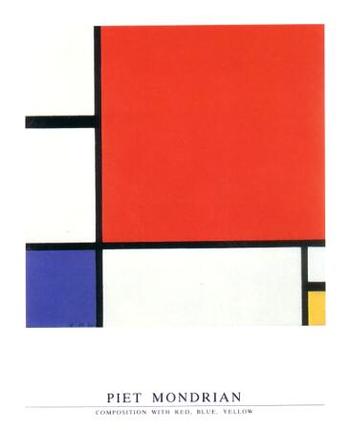

Piet Mondrian, who was one of the earliest artists to practice the new, revolutionary form of non-representational art—that is, producing art with no recognizable subject matter, no humans, or landscape or animals or bugs or whatever—uses very similar geometrical solids to reclassify all of existence into sensations and color forms. Mondrian is more correctly classified as a constructivist, or cubist, and he uses the same tools to re-identify nature as Euclid developed to help classify the structure of the world. This is his “Composition with red, Yellow and Blue” which was painted in 1930, a full eighteen years after Kandinsky created the first painting in this field. But there were other early pioneers in the non-representation field who exhibited a more mathematical aesthetic in liberating the object than we see in the first works than the great Kandinsky. Umberto Boccioni (1912), Frank Kupka (1913), Olga Rozanova (1913), Liubov Popova (1914), Felix del Marle (1914) come quickly to mind,

though none leap to consciousness as quickly as Kasimir Malevich. Malevich begins this work before 1910, and by 1913 he has produced such works as “samovar” in which the (samovar) object is dissected and moved to different places in the visual field on the back of geometrical objects. But it is in 1915 that we are introduced to his extraordinary “Black and red Square”, where we find that he has removed all representation of objects—not only that, he has removed almost all of the forms, period.

On the other hand there is certainly a very long history of artistic adventures which have no recognizable subject, though the artists in these cases I am relatively certain about were not trying to replace the known stuff of our world with the not-yet-known. Geometrical artistic expression at its base has been seen in mazes, labyrinths and mosaics for thousands of years. I guess you could even make a case for architecture fulfilling this role as well it the buildings were taken as art forms. But I’m interested here mostly with the artist intentionally choosing to obscure the known subject.

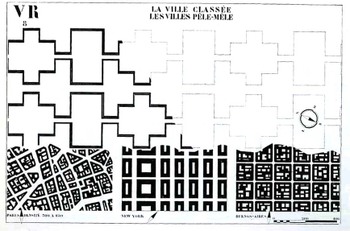

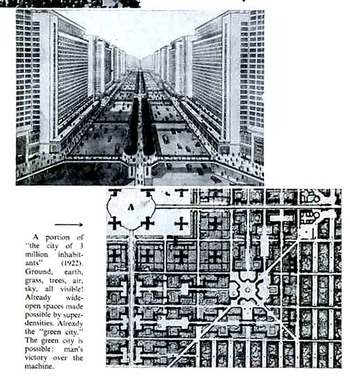

This leads to the troublesome forms of the French architect Le Corbusier (Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris, 1887 –1965). Leafing through his The Radiant City (Elements of a Doctrine of Urbanism to be Used as the Basis of Our Machine-Age Civilization, 1933) is a confusing affair. As much as the man wants to rectify and save the world (his words, salve me fons pietatis) with his geometrical cities, replacing the mess of disorderly human civilization, his results, while giving a crispy clean order, are formidably lifeless (to me, at least), the organic and messy bits of human life de-fractured and placed in 90-degree containers. Le Corbu complains about the American successes, there in 1930 or so, saying that the U.S. is a monument of achievement but for achieving the wrong things. A little later in 1932 and 1933 however he does take time to make positive comments about the interesting experiments going in Fascist/Mussolini Italy and Stalin’s Soviet Union…it was common I know for thinking people to have such harmonious thoughts about these regimes, but there were plenty of others who kew and wrote about what was

really happening in those places, and Le Corbu was not one of them.) The so-called positive elements of American advancements that Corbu took away with him back to France-- Taylorist and Fordist (Henry was a vehement anti Semite and Nazi sympathizer) strategies adopted from American models to reorganize society—I think come vividly alive in his geometrical replacement of human habitation—call me old fashioned, but I just don’t like it. I also don’t like it because it smacks so much of his disgust of capitalism (which he talks about as consumerism) and of his own right-wing political beliefs. Le Corbusier followed these thoughts into the camps of philosophies like the right-wing syndicalism of the French politician Hubert Lagardelle. These also eased him into a position with the traitorous Vichy government during the Nazi occupation of France during WWII—he did cut ties with it in 1942, though only after the architectural plans he had developed for various projects were rejected.

[Another leading 20th century architect, Philip Johnson, had his own problems with admiration of fascist ideas, though the amoral and whorish Johnson would’ve have seen these ideas as “problematic” only insofar as they would keep them from working. He was a decade-long Nazi sympathizer, and among many other things actually followed the Nazis as they stormed their way through Poland—something Johnson described as a (positively) “stirring” experience. He was in a separate class from the kinda-stupid Charles Lindbergh and the empty-suited-but-still-dangerous Prince Harry as Fascist trumpeters. He was more on the level of detestable fascist intellectuals like Martin Heidegger and Ezra Pound. He was awful.]

It just so happens that two of the most towering names in 20th century architecture were embroidered into the fabric of Fascism, and I think that these ideas burn their way directly through the geometrical imagination of Le Corbusier. His brand of geometries lead us towards the human cog-and-wheel, tight-box, suffocating proclivities of his right-wing extremism, and is perhaps the worst sort of illustration for the use of that beautiful branch of mathematics

Just for the sake of clarity I've included this photo of Henry Ford becoming the third recipient of the Nazi Grand Cross of the German Eagle, presented by Karl Kapp, German consul-general of Cleveland (left), and Fritz Hailer, German consul of Detroit (right). The other two recipients were Benito Mussolini and Count Ciano.

Comments