JF Ptak Science Books LLC Post #75

Some of the fundamental discoveries and their announcements in the history of science have come with great fanfare—and some have come with barely a notice. Granted their impact would not be felt for some time to come, but, still, there are some fabulous champions of understatement.

Joseph Lister (1827-1912) came quite close in 1871 to the discovery of penicillin—as had Louis Pasteur (1822-1895), Jules Francois Joubert (1834-1910) and William Roberts (1830-1899)—but his research in this area was abandoned when he wasn’t able to identify the agent in the mold he found in urine which inhibited further growth of bacteria; he then proceeded with his discoveries in the antiseptic procedure in the operating room (sanitizing the instrument and the surgeons) instead Lister’s great work seems exceptionally simple and obvious to us here in the present, but it wasn’t back then, which is why he was the first to do it, saving the lives of thousands of people by increasing their chances of serving surgery by reducing the chances of infection (caused by the surgical procedure itself). Yet his initial announcements, couched in reflective Victorian drama less scientific prose, never really hinted at the greatness which lurked just below the surface of his announcement, "Antiseptic Principle of the Practice of Surgery" in Volume 90, Issue 2299 of The Lancet published on 21 September 1867. It actually took a number of years for physicians to react positively to Lister’s phenomenal discovery, called by Dr. Henry Morris, ‘probably second only to Pasteur’s contribution to the saving of human lives’.

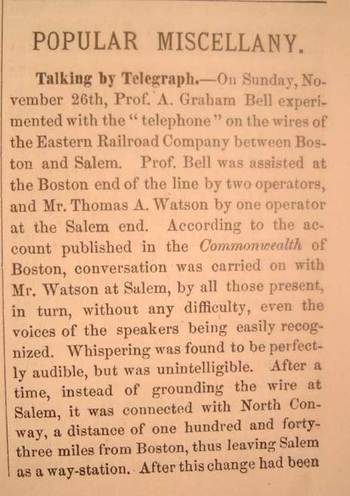

One of the earliest mass popular announcements of Alexander Graham Bell’s invention of the telephone is in The Popular Science Monthly for February 1877—though you’d be a little hard pressed to find it off-hand in this 130pp issue. Following twelve articles (including George Beard on “The Physiology of Mind Reading” and Chamberlain’s “Nature and Life in Lapland”), and following seven pages of literary notices, and following another five pages of “Popular Miscellany”, one may find the slight reference to the telephone. (Pictured here is the two-page spread in which the Bell story is announced—don’t be careless, or you’ll miss it.)

The article, or notice, is called “Talking by Telegraph”, and recalls the Sunday of 26 November in 1876 when Bell’s invention is first revealed, using parenthesis (“telephone”) when referring to the instrument. The story is less than 200 words long and is tucked away in almost total obscurity. There is no mention of its possible use or importance.

Such was also the case with the announcement of the Wright Brothers’ first successful powered flight in 1903. The announcement in Scientific American was far less than auspicious, given two paragraphs almost at the end of the weekly issue in the automotive and aviation section. Actually their earlier successes in unpowered gliding flight in 1901 were treated with similar nonchalance in the Scientific American as well as other popular magazines (of LIFE-like stature in those times), including a fleeting reference in the Illustrated London News and the Illustrierte Zeitung (Leipzig). It took almost no time at all following the Scientific American publication for the rest of the thinking world to react with proper enthusiasm to their spectacular accomplishment.

Our last example here is that of Philo T. Farnsworth (1906-1971), inventor of the first all-electronic television, owner of a spectacularly geeky first name, and one of Time Magazine’s 100 Most Influential Americans of the 20th century

Perhaps some of the downplay of Farnsworth’s annoncuement and achievement was diluted by the longish list of precursors to his invention—the electro-mechanical television for example was the object of the work of Alexander Bain, Paul Nipkow, Aleksandr Stoletov, Karl Ferdinand Braun, Boris Rosing, Herbert E. Ives, and John Logie Baird, while even the electronic television was nearly completed by Boris Rosing, Alan Archibald Campbell-Swinton, Kalman Tihanyi, Vladimir Zworykin and Kenjiro Takayanagi. Nevertheless the achievement of the 23-year old boy wonder still found an enormous pinnacle of understatement, all things being equal. In the article by Fasrnsworth and Harry R. Lubke, “Transmission of Television Images”, in Radio, December 1929, the authors describe their breakthroughs, particularly with what they called their “image dissector”, which differentiated them from the major aspects of the Zworykin invention. With photographs of the invention as well as the successful televised transmission, the authors go on to say that the transmission of moving pictures “could well be considered as having entertainment value”. Indeed. There was some patent litigation ahead, particularly involving Zworykin and RCA, but by 1935 Farnsworth prevailed, though somehow not economically.

Comments