[Atomic Bomb Control and Atomic Energy] Haskins, Caryl P. Two drafts of “Atomic Energy and United States Foreign Policy”, published July 1946 in Foreign Affairs. Two versions, one 37pp and the other, presumably an earlier version, 28pp (pp 1-28, incomplete). Both are original carbons on tissue paper. The two documents: $500

- Dr. Caryl Haskins (1908-2001, Ph.D. Yale ’30 (E.E. at 22), Ph.D. Harvard 1935; LL.D. Carnegie Institute Technology 1955) was a close and long-time friend of the great Vannevar Bush with whom he throughout World War II at the OSRD, as well as executive assistant to Bush at NSRD 1941-1945. He was research associate at MIT 1935-1945; he was on the Scientific Advisory Board of the Army and Navy, 1947-8; Research Consultant to the Secretary of the Army, 1950; Executive Research Consultant to the Secretary of State 1950-1972 Haskins was on the board of Scientific advisors to President’s Truman and Eisenhower, and succeeded Bush as president of the Carnegie Institution (1956-1973).

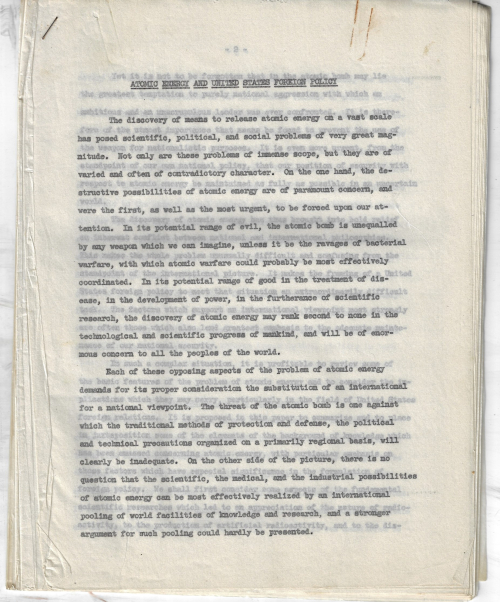

What I find remarkable about this paper is its prescience regarding MAD, the need for international regulation and control, and the absolute belief that the U.S. could not rely on its monopoly of weapons and intelligence even in the short run. He reasons some ways in which to deal with sharing information, restricting the growth of a weapons culture, and the use of atomic energy.

What I find remarkable about this paper is its prescience regarding MAD, the need for international regulation and control, and the absolute belief that the U.S. could not rely on its monopoly of weapons and intelligence even in the short run. He reasons some ways in which to deal with sharing information, restricting the growth of a weapons culture, and the use of atomic energy.

Haskins sees the delivery of atomic bombs by “long range rockets”, and that the temptation for developing an atomic arsenal would curtail expenses for military development by possibly as much as 100-1. (He mentions at one point that 10,000 atomic bombs could be used to secure world domination, at a cost of only $10 billion (or 10 Iowa-class battleships)—making this highly appealing. (He was not referring to the U.S. in this.) He goes on to say that without guidance in atomic energy and control of atomic weapons that an exchange of two (or multiple) countries with such weapons “would be largely destructive of civilization as we know it”.

Haskins also makes the case for the U.S. not to be isolationist in these regards, “and not count on the security of a monopoly of knowledge”.

Haskins was certainly sounding a very considered, scientific, reasoned alarm about what may turn out to be a devastating near-future with uncontrolled atomic weapons. (This was written in 1946, three years before the Soviets exploded their first bomb. In 1946, Lee Groves thought it would take 20 years for the Soviets to develop a bomb; James Byrnes gave them 7-10 years; and Bush-Conant 3-5 years. Some scientists put it sooner than that. My impression is that Haskins was on the side of the bomb coming to the USSR much sooner rather than later, hence this urgent article in Foreign Affairs.

Here’s an interesting notice on this article by Haskins:

- “We therefore cannot count on maintaining our security through a monopoly of fundamental knowledge in the atomic field […]. Further, our monopoly of technical information and facilities is limited and is diminishing. At present we do have a monopoly of stockpiles of raw materials and finished atomic bombs, and we are equipped with gigantic plants for producing these materials. Within something like ten years, however, our monopoly in technology may have disappeared completely, whatever the policy we now adopt with respect to international action.”-- This could almost pass as modern commentary for the U.S., but it was written 71 years ago (July 1946) by Caryl P. Haskins, then deputy executive officer of the National Defense Research Committee, who conveyed a heightened level of concern that the U.S. would lose its monopoly in nuclear science and technology for military applications. This created a direct threat to the U.S. and the world as the Soviet Union leveraged nuclear energy in its pursuit of military primacy over America and geopolitical dominance in Europe and Asia. The genie was out of the bottle and nuclear science was in the public domain. Consequently, America had a peer competitor militarily and its national security was at risk. David Gentile, Forbes, Sept 19, 2017

Comments