JF Ptak Science Books

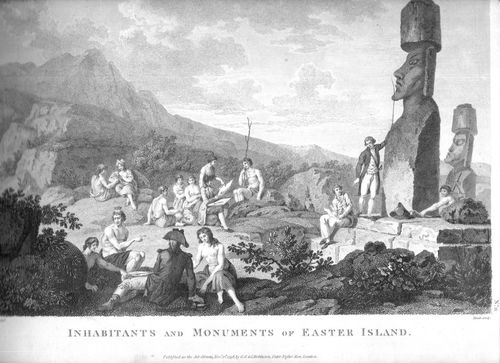

- La Perouse, "Inhabitants and Monuments of Easter Island", London, 1798. 14x9". Original engraving. SOLD

The "Easter" part of Easter Island is fairly ironic--new, rising, hopeful connotations packing something not-so-joyful. I was looking at this engraving from the bookstore, an image from a famous exploration journal of Captain Jean-François de Galaup, comte de La Pérouse, showing a landing party and very western-looking Polynesians. La Perouse was off on a journey that would take him along the trail of Captain Cook, a scientific/ethnographic/cartographic expedition (along with the appropriate trailing or leading religious/economic benefits of such a thing) that landed him on the island 9 August 1786. He left Brest on 1 August the previous year, and he would venture round-the-world, or almost, as he would never make it home, disappearing along the northwest coast of North America in 1789. His journals did complete the voyage, however, being taken back to France by a British ship in Australia.

The island is so-named because it was first recorded by a European, Captain Jacob Roggoveen, Easter 5 April, 1722. La Perouse was there 64 years later, when things were already quite heated, in a most unfortunate way, for the two clans who shared the island, each already suffering substantial losses, as la Perouse found the place sparely inhabited.

As you can see there are a few shrubs in the foreground and some other bits, but there are no trees. Easter Island was by that point largely denuded of trees, making it impossible for the islanders to build boats to fish, and their crops ultimately failing because of the attendant problems erosion and wildlife, making it difficult for much to survive on the island. The clans set at each other, and had bitter fights, resulting later on in the clans toppling in spite the great stone figures of the opposite clan. Easter Island became a port of call for slavers, and the population began to disappear into greed and economic lust.

This was still decades in the future from the la Perouse expedition, his work being published posthumously nearly ten years after the captain's death.

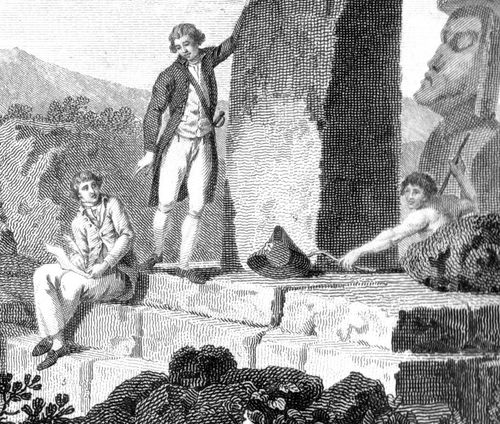

In this image, though, we see a rather playful interaction between the sailors and the islanders. In the foreground-center we see an officer with two men and a woman, one of the men fingering a piece of cloth while the officer is no doubt otherwise distracted. In their background two women are seen using a mirror; to the right of them is a small group watching one of the officers draw an image of one of the Moai. At right, around the Moai, two officers make observations for the ethnographic record, while around the corner at the monument's base an island uses a stick to try to steal one of the officer's hat.

The Maoi were still standing in 1798. Later in the 19th century, though, after devastating attacks on one another, every monument was toppled. As were the people. There's really not that much to the Easter-y history of the European part of the island's history, and so the irony of its naming.

Comments