Cooley, Austin G. How to Receive Radio Pictures at Home. New York: Radiovision Corp, 1928. 1st edition. 26pp, 2 folding blueprints 4to. Printed wrappers. Very good copy. Some wear and dirt on front wrapper. $450

JF Ptak Science Books Post 1415

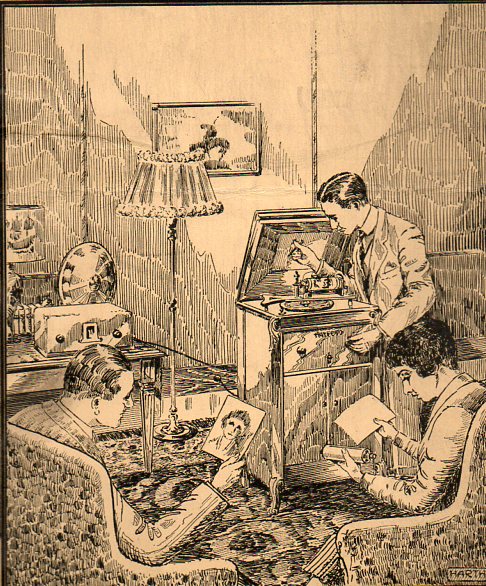

Tomorrow seemed to be almost there to readers of this pamphlet, what with the idea of looking at pictures relating to the radio broadcast you were listening to looming before a slightly disbelieving mind. The fact of the matter though is that this breakthrough by Mr. Austin G. Cooley1--basically attaching what we would know today as a fax machine to a radio cabinet which would receive and print images relating to the show being heard--was rubbing up mightily against the real wave of the future, the television.

Tomorrow seemed to be almost there to readers of this pamphlet, what with the idea of looking at pictures relating to the radio broadcast you were listening to looming before a slightly disbelieving mind. The fact of the matter though is that this breakthrough by Mr. Austin G. Cooley1--basically attaching what we would know today as a fax machine to a radio cabinet which would receive and print images relating to the show being heard--was rubbing up mightily against the real wave of the future, the television.

Mr. Cooley's invention of the Rayfoto just didn't quite fit the demands that would soon be established and met by television. The idea of practical television goes back a fair way2, at least to Arthur Korn in the late 1890's, which much work being done on both broadcast television and facsimile transmissions. But tv was definitely a high scent in the air when Cooley published his Rayfoto pamphlet in 1928--as a matter of fact, this was the same year in which the first television license was granted (to Charles Jenkins, W3XK). And just two years later the BBC would begin regular television broadcasts, while also in 1930 Mr. Jenkins initiated another television-first, the t.v.commercial.

"No greater thrill awaits the radio experimenter than receiving his first picture through the ether…Not many months will pass before picture broadcasts will be a part of every radio broadcast"--A. Cooley, 1928

So the time was definitely note ripe for Cooley's idea as an image supplement to radio, though it did have other possible applications--like the "fax" delivering newspapers to your home--though they are not listed in the pamphlet.

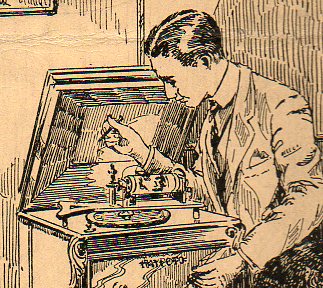

What we see here the drum of the apparatus (we don't see the three-tray developer/fixer wet set-up inside the apparatus), one of the listeners retrieving an incoming vision-image, something that evidently took quite some time, depending on the image and the ways in which the developing trays have been set. Dark images might've taken the entire length of a 15-minute broadcast to transmit and print; other, simpler efforts took less time.

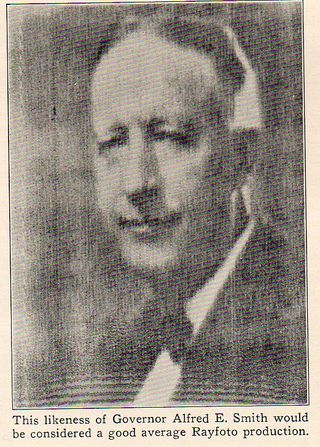

Here's an example of a successful, medium-quality image that one could expect using Cooley's Rayfoto system:

It doesn't look like much now, and maybe it wouldn't've looked like much to people familiar with the new television. But even a grainy, static image accompanying a voice performance is a fabulous thing when compared with never having seen anything like it before, never having had such an experience, if even only as a novelty.

_______

Notes:

1. Cooley, Austin G. How to Receive Radio Pictures at Home. New York: Radiovision Corp, 1928. 1st edition. 26pp, 2 folding blueprints 4to. This unusual publication describes the construction and use of an apparatus which would receive broadcast (facsimile) images that would be used to illustrate radio transmissions/shows. The idea (in this form of illustrating radio shows) at this date would be reduced to almost-nothingness once television entered the picture in the next year or so. Still, it was an elegant idea to illustrate the spoken word.

This system was offered by Austin G. Cooley (1900-1993), inventor of the Rayfoto system, "the first authentic radio picture apparatus". This was a very early attempt at mass entertainment via a mechanical medium that proved ineffective by 1929/1931 against the advances of television. (The radiovision method was something like a facsimile device, offering a static image every now and again, and was completely outclassed by the moving image).

2. Followed by Paul Nipkow's rotating discs in the earliest part of the 20th c, then by Vladimir Zworkin's iconoscope (1923), Charles Jenkins and John Baird's television of 1924, and then of course by Philo Farnsworth's 1928 image dissector.

Comments