ITEM 1) William Hutton. A Brief for Sterilization of the Feeble-Minded. 12pp. From the library of H.L. Mencken. Good condition. $95

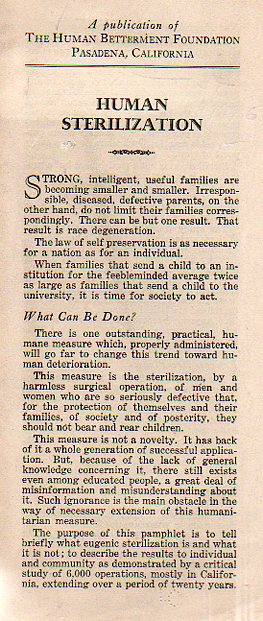

Item 2) . Human Sterilization. A publication of the Human Betterment Foundation of Pasadena, California. 8x3 inches. 12pp. Good. $95

ref: JF Ptak Science Books Post 1335

There are so many ways of spelling "n-a-z--i" without using a "z". Or the "n". The vowels come in handy, though. The Human Betterment Foundation of Pasadena, California did just that, as did the Association of Ontario Mayors, the Eugenic Society, and many other correct-thinking associations and societies. What these people had in mind was the raising of the genetic good through the malleable confusion of human rights issues resulting in the forced

There are so many ways of spelling "n-a-z--i" without using a "z". Or the "n". The vowels come in handy, though. The Human Betterment Foundation of Pasadena, California did just that, as did the Association of Ontario Mayors, the Eugenic Society, and many other correct-thinking associations and societies. What these people had in mind was the raising of the genetic good through the malleable confusion of human rights issues resulting in the forced

"asexualization" of the lesser elements of society--forced sterilization of inmates in state-run mental and correctional institutions, (I've written about sterilization and eugenics earlier on this blog, here, though the pamphlets I'm writing about today are different.)

To paraphrase the good doctor Hunter Thompson, ("when the going gets tough the weird turn pro"), the Nazis did that, becoming complete beasts, horrors even to their own horror, almost unimaginably so. (As a matter of fact, they were so bad that a certain percentage of the population believes that the Holocaust and the Nazi experimentation didn't happen because, among other, race-hating reasons, the crimes were just too enormous to be true.) But before eugenics studies were molded into what the Nazis needed they provided ample justification to other groups. before the Nazis were elected to power in 1933. These American groups weren't nearly on the same level as the Nazis, but they did create their own levels of hell, just not as deep and as profoundly grotesque as the Nazi-version. But it was something very deeply disturbing.

To paraphrase the good doctor Hunter Thompson, ("when the going gets tough the weird turn pro"), the Nazis did that, becoming complete beasts, horrors even to their own horror, almost unimaginably so. (As a matter of fact, they were so bad that a certain percentage of the population believes that the Holocaust and the Nazi experimentation didn't happen because, among other, race-hating reasons, the crimes were just too enormous to be true.) But before eugenics studies were molded into what the Nazis needed they provided ample justification to other groups. before the Nazis were elected to power in 1933. These American groups weren't nearly on the same level as the Nazis, but they did create their own levels of hell, just not as deep and as profoundly grotesque as the Nazi-version. But it was something very deeply disturbing.

The Human Betterment Society put the issue quite simply in their slim little pamphlet, Human Sterilization--to save ourselves from "race degeneration" society had to act and restrict 'defective" men and women from bearing and rearing children. There aren't that many pages in this publication but they each present some astounding assertions, perhaps the most shocking of which is that this society had its eyes on a larger prize--the country was burdened by as many as 18 Million people with mental disease, who "put a charge and a tax on the population" and who would "cost a billion dollars a year" to take care of. The Human Betterment people do not say outright that 18 million people should be sterilized, but the statements come in the middle of a pamphlet making the case for sterilization, so we are left with the determinant that riding this people from the gene pool would be a desirable outcome.

Dr. William Hutton makes the case for the humanitarian treatment of the treatment espoused in the title of his A Brief for the Sterilization of the Feeble-Minded (1936). "It would be unjust and anti-social to withhold the privilege of sterilization from the victims of mental disorders (the insanities)..."(emphasis mine). He dives into the deep-end of the sterilization issue, making the cse for dealing with the "blind, deaf-mutes, haemophilicacs and brachydactyly (deformed fingers)" in the same manner.

Of course the Nazis performed all manner of sterilizations before 1939 and before they started to simply exterminate entire populations of who they considered to be human beings unworthy of life. The eugenics people didn't want to kill people--they just wanted to take away all of their reproductive rights, forever.

As it turns out, the list of the types of people who were subject to enforced, state-organized sterilization got a little shadow-y around the edges, enough so that prisoners or mental patients accused of "moral terpitude" could include, say, poor women forced into prostitution. The lateral motion of these sorts of issue were decided by different state agencies--in New Jersey for example it was the Board of Examiners of the Feeble-Minded; in Indiana, it was a board of "eugenics experts" (who were to be paid no more than $3 per case).

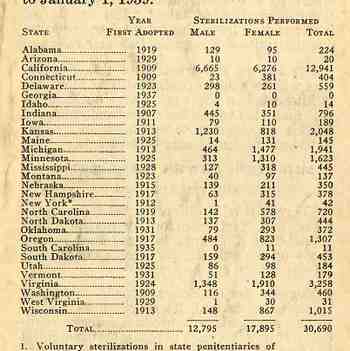

The reach of sterilizations varied by state--some states did not have any laws regarding enforced sterilizations, though most did--the reach of the practice varied from state to state as well, some (like New York) reaching beyond the state penal institutions, mental hospitals and "homes for the feeble-minded", and then right down into reform schools for boys and girls (with Michigan looking into industrial schools as well). Some states--like Kansas--reached across these lines into the lives of epileptics; Michigan did not hunt for epileptics but did so for "imbeciles". Oregon seemed to cast the widest net, including the "feeble-minded, insane, epiletpic, habitual criminals, moral degenerates, and sexual perverts" found in any institution maintained at the public's expense who condition was found to be "inadvisable for procreation". Maine on the other hand simply included "other forms of mental disease".

By 1933 state-sponsored sterilizations of these classes of people reached the following totals:

And so it almost ends, the story of sterilization growing weak and stale by World War II, exhausted and failing under its own exhaustion and failure. The sterilization of sterilization really begins with the Supreme Court Decision of 1942, the Court finding unanimously that (in Skinner v Oklahoma) that Mr. Skinner's--a chicken thief--right were being violated when faced with castration. Justice William O. Douglas wrote: "[S]trict scrutiny of the classification which a State makes in a sterilization law is essential, lest unwittingly, or otherwise, invidious discriminations are made against groups or types of individuals in violation of the constitutional guaranty of just and equal laws."The practice continued with less abandon and more restrictive uses into the Nixon administration, which even as late as 1970 increased Medicaid funding for sterilizations, a weirdly appropriated funding that seemed to dramatically increase the sterilization of poor blacks. Forced sterilization breathed its last in Oregon in 1981.

Comments