JF Ptak Science Books Post 1494

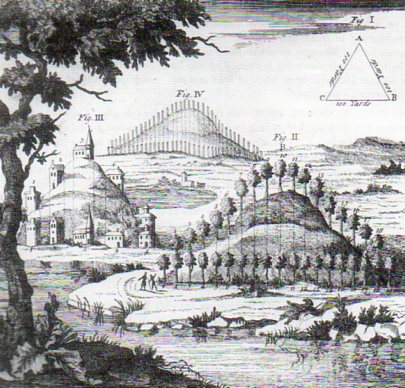

It was this lovely engraving from Richard Bradley's A General Treatise of Husbandry and Gardening..., printed in London in 1721/2, that brought up the issue of structure in creation, and how that issue was in one way approached by the new tool in the scientific toolchest, the microscope.

"...the Contrivances of the Almighty Creator is as visible in the meanest Insect of Plant, as in the greatest Leviathan or the strongest Oak. To touch upon all the Wonders this Instrument shews us would be infinite"--William Molyneux, on the microscope, in his A Treatise of Dioptricks in Two Parts (1692, quotation fro the second edition of 1709 via Marjorie Nicholson's Science and Imagination, Cornell, 1956.

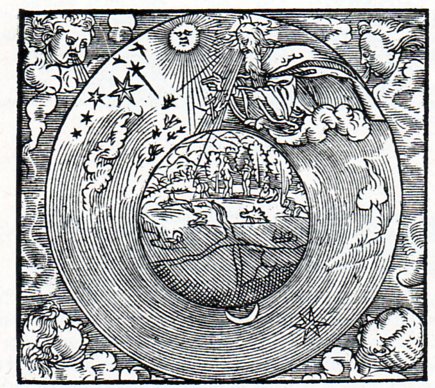

The question that the microscope---newly introduced and popularized by Robert Hooke in 1665 and Anton van Leeuwenhoek in 1674--was so able to address at this time was the question of the structure of things, and whether the Almighty Creator allowed for unrestrained creativeness or if the cosmos was subject to patterns and forms. The microscope was so tremendously nimble that it allowed its observers the luxury of finding "correct" answers on either/both sides of the issue, that arguments could be well made and sustained for variety and regularity. But of course all found the reason for either end of the argument deeply seated in the e hands of god, as seen in the lovely quote below by the great early microscopical popularizer, Henry Baker1.

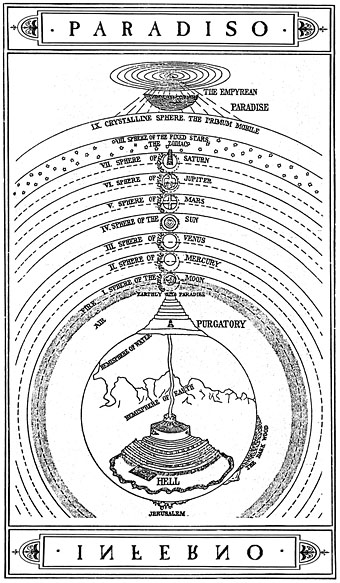

But this is just the tiniest bit of a nod at the question of structure in the history of science, a search for the relationships between, well, things small and large: atomic, molecular, cellular, organism, population, ecosystem,solar system, universe. The issue of structure may be the only issue--perhaps if you were made to select one question to have answered, automatically, an answer for everything, it might be this issue of how things stand in relations to one another.

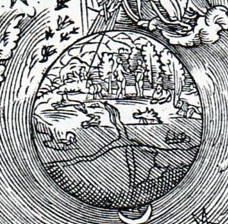

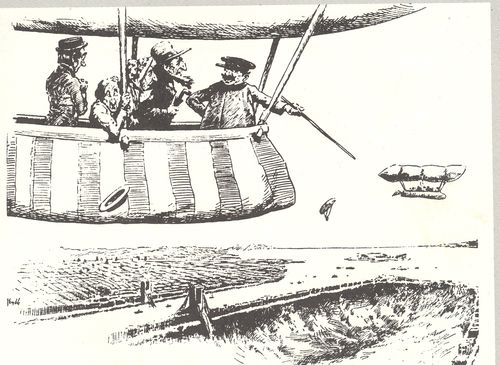

Which gets us to this 1721 engraving of a tree-covered hill, following the designs of a human creator, a re-animator of the natural landscape according to a theory of beauty, part of which hangs in the form of a triangle in the right-hand upper corner. A three-sided strategy of the relationships in nature, provided by a human vision. A very small appreciation of an attempt to recognize the relationships between things, and in this case, the beauty of trees and hills.

Notes:

1. "The first Part of this Treatise discovers in the Particles of Matter composing Salts and saline Substances, Properties whose amazing Effects would surpass all human Belief or Conception, were we not convinced of their Truth by the strongest ocular Demonstration. That beautiful Order in which they arrange themselves and come together under the Eye, after being separated and set at Liberty by Dissolution, is here described and composed but one kind of figure, however simple, with Constancy and Regularity, we should declare it wonderful: What must we then fay, when we see every Species working as it were on a different Plan, producing Cubes, Rhombs, Pyramids, Pentagons, Hexagons, Octagons, or some other curious Figures peculiar to itself; or composing a Variety of Ramifications, Lines, and Angles, with a greater Mathematical Exactness than the most skilful Hand could . draw them?"

"Sensible of my own Ignorance, I pretend not to account how this is done: all I know is, that Chance or Accident cannot possibly produce Constancy and Order, nor inert Matter give Activity and Direction to itself. When therefore these Particles of Salts are seen to move in Rank and File, obedient to unalterable Laws, and compose regular and determined Figures, we must recur to that Almighty Wisdom and Power which planned out the System of Nature, directs the Courses of the Heavens and governs the whole Universe." -- Original, shorter quote of Henry Baker in his Employment of the Microscope (1753) found in Nicholson's book; the above, longer version is from the 1764 (and second) edition, found here.