JF Ptak Science Books LLC

Here's a few interesting images I've collected and just want to make a picture post of them.

Continue reading "Sports Photos, 1890-1940, Mostly Women (Picture Dump)" »

JF Ptak Science Books LLC

Here's a few interesting images I've collected and just want to make a picture post of them.

Continue reading "Sports Photos, 1890-1940, Mostly Women (Picture Dump)" »

Posted by John F. Ptak in Photography, history, Picture Post/Image Dump | Permalink | Comments (2) | TrackBack (0)

JF Ptak Science Books LLC Post 883 Blog Bookstore

I enjoy antiquarian window shopping, browsing photos or

engravings that depict goods for sale-- especially if the prices are posted. I

came back to this deep-in-the-Depression-fantastic photo made in 1935 by Berenice

Abbott (Springfield, Ohio, 1898-1991). Blossom

Restaurant, NYC was part of Abbott’s effort funded by the WPA, this time as

a part of her Changing New York Project, and captures the restaurant and

neighboring barber shop at 103 Bowery.

The two businesses actually occupied the first floors and basement

(respectively) of the Boston Hotel, a standard flop house in a tough and

distressed part of the city that rented beds by the day, with 249 small

door-less cubicles offering a decent place to spend the night for 30 cents1.

30 cents seems to be the going rate for a bunch of things going on in this picture—30 cents for a night in the hotel, 30 cents for the better offers of Morris Gordon’s restaurant. 30 cents for a haircut and shave, 30 cents for a “women’s hair bob”2 and so on. Which seems about right—a fancy haircut and a decent better-than-average dinner for two will probably cost about the same, today.

If you were really on a tight budget, 30 cents would buy you three vegetarian dinners, or 6 offerings of bread and soup, or three visits to the table of meatballs and bans, or pigs feet and kraut.

The price of a stick-to-your-ribs meal of sirloin and potatoes and a pot of coffee also cost about the same as a gallon and a half of gasoline (which cost about 20 cents). The same amount of gas today would get you a serving at McDonalds, or something on that order, and perhaps even a happy take-away for the kids. Perhaps the two even out.

30 cents might get you a loaf of bread, and wouldn’t quite get you a dozen eggs. Now this is remarkable, because if you adjust all of this according to modest CPI measures, the average cost of a dozen eggs in 1935 was 37 cents, or (according to the US Census website generating 1935 to 2009 prices adjusting to CPI) $5.84. The bread would cost $4.74 in 2009 dollars, which means that the staples today—milk, bread, butter, eggs, were more expensive in 1935 than today. Ditto gasoline, which cost 19 cents a gallon, or $3 today—actually this would be much more expensive in 1935 as the mileage the cars were getting then (and the octane) was much lower, so the cost of running an automobile was considerably higher. The cost of the car itself, though, still favors the ‘thirties for modest transportation, which came in at about 600 dollars, or just over $9000 in 2009 dollars3.

The 3-cent first class postage stamp of 1935 was more expensive than first class postage in 2009: 47 cents versus 44. When you look at the increases and bitty spikes of the cost of a first class stamp over time the whole thing looks pretty flat.

The average salary for a family of four in 1935 was about

1500/year, which oddly enough is about the same for the poverty guideline level

for 2009 established by the Department

of Health and Human Services (about $23,000).

Minimum wage legislation didn’t begin until 1938, but if you take a look

at one of my earlier posts here on the history of this idea

you’ll see that the recent history of legislating a meaningful level of acceptance for a base

living wage is mainly disgraceful, with relatively little accomplished (in

adjusted economic terms) for half a century.

(The new minimum wage brings us to about a mid-way point as the highest

minimum wages paid in the 71-year history of the program.)

And so I thank Ms

Abbott again for her beautiful social commentary, and a happy 75th birthday

to this photograph.

Notes

1.A fantastic website and resource for changing aspects of NYC can be found here, at Frank Levere’s Changing New York site. http://www.newyorkchanging.com/

2. I wrote a little bit about the appearance of women-only hair salons in my post “The Staggering Beauty of Barber Shops” http://longstreet.typepad.com/thesciencebookstore/2009/02/the-staggering-beauty-of-barber-shops-naive-surreal-department-22.html

3. Other bits of what stuff cost in 1935:

Flour (5 lbs) 25.3 cents

Bread (lb) 8.3

Round steak (lb) 36.0

Bacon (lb) 41.3

Butter (lb) 36.0

Eggs (doz.) 37.6

Milk (1/2 gal.) 23.4

Potatoes (10 lbs) 19.1

Coffee (lb) 25.7

Sugar (5 lbs) 28.2

Car: $580

Gasoline: 19 cents/gal

House: $6,300

Bread: 8 cents/loaf

Milk: 47 cents/gal

Postage Stamp: 3 cents

Posted by John F. Ptak in Information, Quantitative Display of, Photography, history, Prints--looking HARD/deeply at, Statistics--Fossil, Found, Odd, Forgotten | Permalink | Comments (1) | TrackBack (0)

Tags: Berenice Abbott, Depression, New York City, WPA

JF Ptak Science Books LLC Post 842

In

In

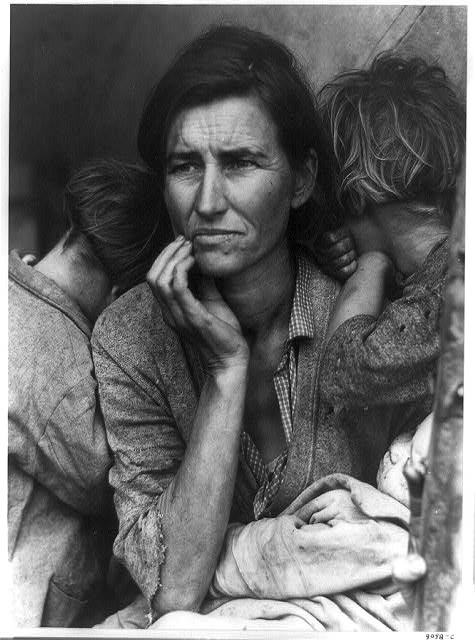

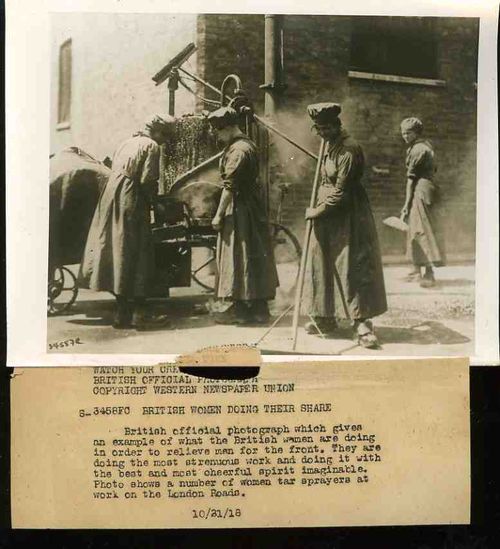

When the end of the War came, so did the appreciation for the women replacement workers—there was bitter feelings in the post-war period because of the weak British economy and a scarcity of jobs. So the women who took the jobs of men to help the country’s war effort and free up hundreds of thousands of men for war service became an atavistic action, “taking” the jobs of men who had gone out to fight for their country. This of course cost many women their jobs, but the damage had already been deeply done to the pre-1914 British world of the sexual politics of business-being-done, though it would take World War II to really ingrain the appearance of women in the workforce into the national psyche.

I've liked this photo for a long time, seeing things differently in it over the years. It struck me just yesterday that the woman in foreground-right--whose close-up reminds me too of a Madonna, a Mona Lisa of the Tars--looks like a Vermeer character from 400 years ago. Or at least the position of her body does.

Posted by John F. Ptak in Photography, history, Prints--looking HARD/deeply at | Permalink | Comments (3) | TrackBack (0)

JF Ptak Science Books LLC Post 837 Blog Bookstore

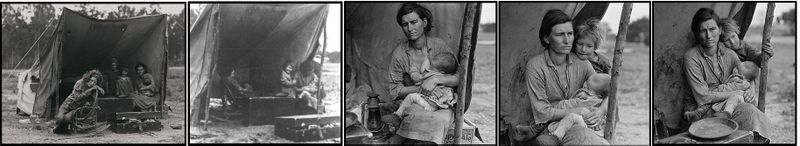

On of the great innovations in a sea of great things accomplished during the Franklin Roosevelt administrations was the formation of the Farm Security Administration, a division of the government established to help farmers through the devastating Dust Bowl and Great Depression. A subset of the FSA was a photographic unit which was set up to document the progress made by the FSA (and provide, I am sure, for some much-needed good news, a hearts-and-minds campaign). This division was headed by Roy Emerson Stryker, who wound up hiring a collection of dream-team photographers unlike any ever assembled for a single purpose. Esther Bubley, Marjory Collins, Mary Post Wolcott, Arthur Rothstein, Walker Evans, Russell Lee, Jack Delano, Gordon Parks, Charlotte Brooks, John Vachon, Carl Mydans, Dorothea Lange and Ben Shahn were sent out all across the country and wound up with the greatest and most beautiful photographic history ever assembled. There were about 77,000 images made, and I recall reading (somewhere) that the total budget for the Stryker group for the years 1936-19421 was about $100,000, meaning that each completed image cost just over a dollar apiece.

On of the great innovations in a sea of great things accomplished during the Franklin Roosevelt administrations was the formation of the Farm Security Administration, a division of the government established to help farmers through the devastating Dust Bowl and Great Depression. A subset of the FSA was a photographic unit which was set up to document the progress made by the FSA (and provide, I am sure, for some much-needed good news, a hearts-and-minds campaign). This division was headed by Roy Emerson Stryker, who wound up hiring a collection of dream-team photographers unlike any ever assembled for a single purpose. Esther Bubley, Marjory Collins, Mary Post Wolcott, Arthur Rothstein, Walker Evans, Russell Lee, Jack Delano, Gordon Parks, Charlotte Brooks, John Vachon, Carl Mydans, Dorothea Lange and Ben Shahn were sent out all across the country and wound up with the greatest and most beautiful photographic history ever assembled. There were about 77,000 images made, and I recall reading (somewhere) that the total budget for the Stryker group for the years 1936-19421 was about $100,000, meaning that each completed image cost just over a dollar apiece.

One of the most compelling of all of these images was from a series made by the new-hire Dorothea Lange (1895-1965) in 1936. On the tail end of a month-long road trip she was nearing the end of her day when she spotted a hand-lettered sign reading “Pea-Pickers Camp” by the side of the road near Nipomo, California. She briefly considered stopping but went ahead, and for the next 20 miles of hard road continuously questioned her decision. Unable to shake her better judgment, she turned around and drove back to the turn-off for the camp. Lange drove down the dirt road and found a ramshackle assembly of tents, one of which contained an exhausted mother sitting forlornly with her children, sheltered in a tent fashioned to the rear of the woman’s tireless car. Lange spent only 10 minutes with the woman, making five exposures. She learned that “the crops had frozen, and the woman and children were living on vegetables scavenged from the fields, and the few birds that the children managed to catch. The mother could not leave; she had sold the tires from her car".

One of the most compelling of all of these images was from a series made by the new-hire Dorothea Lange (1895-1965) in 1936. On the tail end of a month-long road trip she was nearing the end of her day when she spotted a hand-lettered sign reading “Pea-Pickers Camp” by the side of the road near Nipomo, California. She briefly considered stopping but went ahead, and for the next 20 miles of hard road continuously questioned her decision. Unable to shake her better judgment, she turned around and drove back to the turn-off for the camp. Lange drove down the dirt road and found a ramshackle assembly of tents, one of which contained an exhausted mother sitting forlornly with her children, sheltered in a tent fashioned to the rear of the woman’s tireless car. Lange spent only 10 minutes with the woman, making five exposures. She learned that “the crops had frozen, and the woman and children were living on vegetables scavenged from the fields, and the few birds that the children managed to catch. The mother could not leave; she had sold the tires from her car".

Her photograph created an American Madonna in her Migrant Mother.

George P. Elliott, writing in the introduction for the Lange retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art (New York), grasped the essence of the image:

"For an artist like Dorothea Lange who does not primarily aim to make photographs that are ends in themselves, the making of a great, perfect, anonymous photograph is a trick of grace, about which she can do little beyond making herself available for that gift of grace".

Lange describes her encounter as follows:

"I saw and approached the hungry and desperate mother, as if drawn by a magnet. I do not remember how I explained my presence or my camera to her, but I do remember she asked me no questions. I made five exposures, working closer and closer from the same direction. I did not ask her name or her history. She told me her age, that she was thirty-two. She said that they had been living on frozen vegetables from the surrounding fields, and birds that the children killed. She had just sold the tires from her car to buy food. There she sat in that lean- to tent with her children huddled around her, and seemed to know that my pictures might help her, and so she helped me. There was a sort of equality about it". (From: Popular Photography, Feb. 1960). Lange's field notes of the images read: "Seven hungry children. Father is native Californian. Destitute in pea pickers’ camp … because of failure of the early pea crop. These people had just sold their tires to buy food."

Roy Emerson Stryker, who was in charge of the photography project (History Section) for the FSA said of this image:

"When Dorothea took that picture, that was the ultimate. She never surpassed it. To me it was the picture of Farm Security. She has all the suffering of mankind in her, but all the perseverance too. A restraint and a strange courage".

NOTES

1. The photographic history unit of the FSA morphed into a propaganda arm for the Office of War Information (OWI) in late 1942.

2. Florence Owens Thompson (1903-1983) is the real name of the Migrant Mother.

3. The Library of Congress files for the series of photos

Posted by John F. Ptak in Photography, history, Women, History of | Permalink | Comments (3) | TrackBack (0)

This is the U.S. Army mail depot at Regents Park, London, braced for and under siege by Christmastime mail in 1917. It strikes me that there are not a million items in this photo--at this time in the war there were something like 35 million people in the services for all countries dedicated to the war effort, which is approximately half the number that served in total. If these letters in this picture were bodies, I reckon that there would be five more rooms like this necessary to tell the visual picture of the war dead and wounded. This aside, I initially focused on the guy in the rear with the white shirt and tie, standing there pretty much overwhelmed by the task of moving all of that stuff...and perhaps with the idea that much of the mound would wind up being undeliverable because the recipient was killed. I wonder if that mail was returned, or not?

On the other end of the spectrum is this bizarrely-titled photo of a British soldier "guiding" a traffic signal device...the description says that this is the busiest intersection in all of British-occupied France. Maybe so, but not at this particular time. Perhaps the photographer should've waited a bit to get a different sort of picture to make his point, rather than settle for this lonely (if not beautifully arranged) situation.

Here's the image without the accompanying text, which was supplied for the end-user of the photo by the news service photography supplier.

Posted by John F. Ptak in Contraries, Militaria, Photography, history | Permalink | Comments (1) | TrackBack (0)

JF Ptak Science Books LLC Post 806 Blog Bookstore

Earlier today I made a post on some of the images in my collection of WWI News Service Photographs. (These were photos that were sold by an image agency to newspapers and journals which looked for stock photos of, well, whatever, and after paying a use fee would include the photo in the story they were reporting.) This photo is one of three in a series that show German POWs being marched around a town in France and stopped here and there for a photo. The picture was taken deep into 1918, within a month or two of the end of the war,.when the Germans were already defeated. From the look of things, these soldiers were done: tired, mostly beaten, dirty. They at least had most of their buttons on their coats (which is actually a very big deal, keeping your overcoat closed in cold weather to keep warm and alive), their boots looked warn but intact, and they looked not terrible undernourished (though I doubt anyone in the group weighed more than 150 pounds).

The group is bookended by two remarkable figures: the soldier on the left looks not 16 or so, but with a not-new ground in toughness. He's all smooth face and baby fat, though he has at least survived the grueling fighting. The soldier on the right could be the prototype for any number of propaganda posters that popped up in Berlin in the early 1930's advocating the sold-out but not defeated German soldier of the Great War whose fate must be avenged.

Almost everyone was cupping a ciggy.

Lastly, the guy third from the left seems to be a Canadian guard, not that this group was going to try to escape.

Posted by John F. Ptak in Militaria, Perception, Photography, history, Prints--looking HARD/deeply at | Permalink | Comments (2) | TrackBack (0)

Tags: Germany, Photography, Prisoners of War, World War I

In

my collection of WWI News Photo Service Agency photographs I would say

that half or so of them show scenes like this--semi-informal group

portraits of military support groups. 500 portraits like this seem to

be a lot, and I'm not sure why these images are so well represented.

Except of course that there weren't that many images (overall) of

active-battle scenes.

These bakers, working at a front-line support station, from my read were probably taking a break, and the photographer took the opportunity to draw them together for the portrait. I don't know why they're separated so, but they do look as though they have a real camaraderie--it is just a wonderful picture, full of friendship and loyalty, and I'm sure it has never been published before.

Posted by John F. Ptak in Militaria, Photography, history, Prints--looking HARD/deeply at | Permalink | Comments (0) | TrackBack (0)

JF Ptak Science Books LLC Post 738 Blog Bookstore

I came across another fantastic part of the Library of Congress site: The Life of the City, Early Films of NewYork, 1896-1906. I've quoted liberally from the descriptions of the films, and also provided a chronological listig of many of the films that are found at the site. They are spectacular things, like pieces of eidetic memories, offering wide swaths of minuate detail in corners of pockets of life from a hundred years ago.

NOTE: To view the films just follow the link and click on the MPEG format for best viewing.

NYC Garbage Dumping Scene 1903

Yes, this is what people did when they worked, not so long ago, when thousands and thousands of people worked at making The City go--in the streets picking pulling pushing prying pumping preening polishing purging. What grabs me are the three workers working beneath the horse-drawn carriages, working on the barges, spreading around the waste. The topsiders dump their cargo, letting it fall twenty feet or so, landing very closely to the men below. It seems like an unending process

From the LC site:

"The film shows a wharf where a barge is being loaded with trash from

two-wheeled, horse-drawn wagons. The trash is dumped off the edge of the pier

onto the barge, where men with shovels are spreading the piles of debris. The

camera pans left to the next barge, where four-wheeled carts are shown dumping

excavation rubble. Probably filmed on the East River,

this is one of several New York City Sanitation Department dumping wharves in

operation at the time."

I love what the kids do when they see this camera--they pretty much uniformly stand still, their fingertips pressed together in wonder and worry, and stare at the strange goings-on fifteen feet above the crowd. At one point three officials stroll through the crowds, coming in at top right; they are very sharp eyed, and the one guy at the end of these three looks like every other guy who has played a corrupt NYC official in every other movie made before WWII.

"The view, photographed from an elevated camera position, looks down on

a very crowded New York City street market. Rows of pushcarts and

street vendors' vehicles can be seen. The precise location is difficult

to ascertain, but it is certainly on the Lower East Side, probably on

or near Hester Street, which at the turn of the century was the center

of commerce for New York's Jewish ghetto. Located south of Houston

Street and east of the Bowery, the ghetto population was predominantly

Russian, but included immigrants from Austria, Germany, Rumania and

Turkey. According to a description in a 1901 newspaper, an estimated

1,500 pushcart peddlers were licensed to sell wares (primarily fish) in

the vicinity of Hester Street. At one point the film seems to follow

three official looking men (one in a uniform) as they walk among the

crowd. They may be New York City health inspectors, who apparently

monitored the fish vendors closely."

From the LOC site:

"Filmed from a moving boat, the film depicts the

Hudson River (i.e., North River) shoreline and the piers of lower

Manhattan beginning around Fulton Street and extending to Castle Garden

and Battery Park. It begins at one of the American Line piers (Pier 14

or 15, opposite Fulton Street) where an American Line steamer, either

the "New York" or "Paris," is seen docked [Frame: 0120]. The camera

passes one of the Manhattan-to-New Jersey commuter ferries to Jersey

City or Communipaw [0860]. Proceeding south, the distinct double towers

of the Park Row, or Syndicate Building, erected in 1897-98, can be seen

in the background [0866]. A coastal freighter is next [1560], then

Trinity Church appears, to the left of which can be seen the Surety

Building, as a tug with a "C" on the stack passes in foreground [2032].

Several small steamboats come into view [2136], and the B.T. Babbitt

Soap factory at Pier 6 is seen [2300], followed by the Pennsylvania

Railroad piers (#5 & #4), with a group of docked railroad car

floats [2556], and the Lehigh Valley Railroad piers (#3 & #2), also

with car floats [3030]. Next are the Bowling Green Building

(rectangular, with facade to camera) [3208], the Whitehall Building

(vertical, thin side to camera) [3388], followed by Pennsylvania

Railroad Pier #1 [3630]. Pier A (with a clock tower) is seen with the

New York Harbor Police steam boat "Patrol" at its end [4654]. The

Bowling Green Offices and the Produce Exchange at Bowling Green are

visible in the background. The breakwater (sheltered landing) and the

New York City Fireboat House appears [5270] and the distinctive round

structure, Castle Garden, once a fort and immigrant station, but at the

time of filming the City Aquarium, comes into view [5438]. The camera

then pans east along the Battery Park promenade: the Barge Office (with

tower) is visible in the distance [5804], and further out the Brooklyn

shoreline with the grain elevators at Atlantic Avenue can be seen

[6088]. This view is continued, with only a minor break in continuity,

in the film Panorama of Sky Scrapers and Brooklyn Bridge From the East

River. Together they comprise a sweep around the southern tip of

Manhattan, from Fulton Street on the Hudson to the Brooklyn Bridge."

Brooklyn Bridge to the Battery, waterfront

Another beautiful water-side continuous panorama, from just above the Brooklyn Bridge to the battery.

From the LOC site: "This film depicts the East River shoreline and the piers of lower Manhattan starting at about Pier 5 (the New York Central Pier) opposite Broad Street, and extending to the Mallory Line steamship piers just south of Fulton Street and the Brooklyn Bridge. The film begins with shots of canal boats or barges (from the Erie Canal via the Hudson River) docked at and around Coenties Slip [Frame: 0106]. As the film progresses, the New York Produce Exchange located at Bowling Green, Manhattan, with its distinct tower, comes into view in the background [0346]. Between here and the Wall Street ferry, there follows in order of appearance: steam tugs [0308 and 0422], a wooden hull barkentine [1032] with box barges alongside, a docked iron hull sailing ship, probably British [1448], an ocean steamer with yards on the foremast [1748], a derrick lighter laden with barrels docked at the end of a pier [2134], and a fruit steamer [2612]. In the Wall Street Ferry slip (between Piers 15 and 16) there is a Wall St., Manhattan-to-Montague St., Brooklyn, double-ended steam commuter boat [2896]. The ferry is visible immediately before a shot of the large advertising billboards on Pier 16. The film next shows the Ward Line piers (J.E. Ward & Co., New York and Cuba Steamship Co.) [3040], a Pennsylvania Railroad tug [3190], a derrick lighter [3320], and the Mallory Line piers [3692]. A Mallory Line steamer can be seen on the south side of one of the Mallory Piers [3736]. The camera begins panning out into the East River after passing pier 20, catching the fog bell at the end of pier 21 [3922]. A car float is visible passing under the Brooklyn Bridge [4202]. The pan follows the line of the Brooklyn Bridge eastward to Brooklyn Heights, where the Hotel Margaret (tall building in background) is visible just before the end of the film [4464]. This film continues the view begun in the film Sky Scrapers of New York City From the North River. Together they comprise a sweep around the southern tip of Manhattan, from Fulton Street on the Hudson to the Brooklyn Bridge."

Immigrants Arriving at Ellis Island 1903

Here comes everyone, from everywhere, emerging from a ferry, delivering immigrants from Manhattan to Ellis Island, where the process of the beginning of the rest of the lives of all these people began. Between 1892 and 1954 some 12.5 million people were processed into the U.S. through Ellis, and in the early days, say 1892-1920, most of them looked just like these folks--the grandparents and great-grandparents of a quarter of the country.

From the LOC site: "The film opens with a view of the steam ferryboat "William Myers," laden with passengers, approaching a dock at the Ellis Island Immigration Station. The vessel is docked, the gangway is placed, and the immigrant passengers are seen coming up the gangway and onto the dock, where they cross in front of the camera."

Posted by John F. Ptak in Photography, history | Permalink | Comments (0) | TrackBack (0)

JF Ptak Science Books LLC Post 714 Blog Bookstore

The Klondike Gold Rush, or the great Alaskan Gold Rush, took place at the very tail end of the 19th century (starting 1896/7) along the Klondike River near Dawson, Alaska. It was a wild, woolly (literally) time, with communities of thousands springing up in just a few days--Klondike itself grew almost immediately to 40,000, stretching all human services, food being the scarcest commodity.

One service to humans that was ably met was sexual, filled by legions of prostitutes, some of whom arrived in the Klondike of their own free will, and others, not. This photo, made near Dawson, shows "Paradise Alley" (behind front street) an almost-overnight series of rough-hewn log bungalows sweatily constructed for lonely needs. There were evidently 70 of these little huts, all in a row, each with the woman's name above the door, presumably rendered in chalk. (It seems that the photos I've seen of women in the Klondike show many smiles, but no toothy ones.)

This is a detail from a photo seen in Pierre Berton's The Klondike Quest (a big, beautiful book of high rank for a popular history, interestingly published with a more shouty title in America as Klondike Fever) showing the working women of Dawson working at other trades. I particularly like the picture of the high-collared white-dressed angel-woman witht he axe on her shoulder...and the woman behind her, under the make-shift cloth awning, her hat tiled forward and her hand jauntily on her relaxed hip.

Prostitution wasn't legal, nor was gambling or the encyclopedia of con games that evolved here--but all certainly flourished, with many fortunes made outside the gold fields. Mr. Pantanges started his movie house empire here, and Donald Duck's Uncle Scrooge started his pile of money bags, as did many other people. But the 12.5 million ounces of gold wasn't exxactly distributed with equality to the dozens of thousnds, and probably hundreds of thousnads of people who came to the Klondike looking for their fortunes. I'm certain that in this vast game of winners and losers, there was moreof the later and less of the former.

This image of miners waiting to register their claims gives us a pretty decent idea of the clientelle available to these women. Oy. Seems to me an impossible way to live--for the women, that is.

Posted by John F. Ptak in Photography, history, Prints--looking HARD/deeply at | Permalink | Comments (0) | TrackBack (0)

Tags: ALaska, Dawson, Gold Rush, Klondike, Prostitution

JF Ptak Science Books Post 623 Blog Bookstore

The following two images were found in the Illustrated London News for 30 April 1906, and shows the "shanty town" built near the site of the major destruction in San Francisco following the earthquake of 18 April 1906. Actually the tragedy is more appropriately called the "San Francisco Fire" of 1906, as the major destruction was caused by the raging fires set off by the earthquake. The end result was 485 or so blocks of the city were destroyed leaving a quarter-million people homeless. That this orderly development was referred to as a "shanty town" by a sniffy Brit reporter is appalling--unless of course the offending word meant something different 103 years ago. It looks orderly and well-developed to me. I also happened to notice two small girls in the detail--just about the only people in the picture. They could still be alive....

The bottom two pictures were taken during the conflagration: the first was the fire still raged, and the second was made days after the fire from a tethered balloon observation point.

I made myself 6-foot-long prints of these images; nearly every 2x2 inch area of the enlargement is a picture in itself. These images are clickable and will expand if you click in the expanded version.

For a contemporary film of the event via the Library of Congress, see here: http://loc.gov/item/00694425

Panoramic images via the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, see the following link for these and a number of others: http://loc.gov/search/?in=&q=panorama+san+francisco+fire&new=true&st=

A few eyewitness reports, from the Eyewitnesstohistory.com website:

"Of a sudden we had found ourselves staggering and reeling. It was as if the earth was slipping gently from under our feet. Then came the sickening swaying of the earth that threw us flat upon our faces. We struggled in the street. We could not get on our feet. Then it seemed as though my head were split with the roar that crashed into my ears. Big buildings were crumbling as one might crush a biscuit in one's hand. Ahead of me a great cornice crushed a man as if he were a maggot - a laborer in overalls on his way to the Union Iron Works with a dinner pail on his arm." (P. Barrett).

"When the fire caught the Windsor Hotel at Fifth and Market Streets there were three men on the roof, and it was impossible to get them down. Rather than see the crazed men fall in with the roof and be roasted alive the military officer directed his men to shoot them, which they did in the presence of 5,000 people." (Max Fast).

"The most terrible thing I saw was the futile struggle of a policeman and others to rescue a man who was pinned down in burning wreckage. The helpless man watched it in silence till the fire began burning his feet. Then he screamed and begged to be killed. The policeman took his name and address and shot him through the head." (Adolphus Busch).

Continue reading "San Francisco, 1906: Pictures within Pictures. The Great Earthquake and Fire." »

JF Ptak Science Books LLC Post 600 Blog Bookstore

There are many histories of photography in wartime: early images show cavalry standing at the

ready, troops marching, piles of munitions, heaps of food; later on (as late as

WWI) come actual scenes during the course of battle. War photography changes forever beginning in

the Spanish Civil War, and then of course WWII.

Korea,

Looking through the WWI years in the Illustrated

London News I experienced a creeping realization of a different sort of

perspective in war photography: turning

the camera to look behind the battle.

Turning the camera exactly around, away from the action, hasn’t a good

history in itself. There are some great

examples: when the Golden Spike was

driven at Promontory Point in 1869 someone had the foresight to look the other

way and make a photo—it shows a vast plain, a long double ribbon of rail, a

long series of telephone poles receding into the horizon, and one man. It is

also a scene that looks pretty much the same today, if you took away the small

dedication center that is there. That

was the reality of the day, not all of those RR workers gathered around the two

hot locomotives, the cleanest of them toasting each other and the camera. (If

you look closely you can find some Chinese laborers in among the crowd and also

occasional bits of Confederate uniforms.)

Elsewhere in this blog I told the story of Ed Clark, the LIFE

magazine photographer who wheeled his camera away from where the hundreds of

other cameras were recording the removal of Franklin Roosevelt’s casket from

But it is a different sort of turn-around that struck me for WWI. These are the photographs of the liminal spaces after the fight, the clean up, the gathering of spent ammo, the cleaning of the clothing, the care of the soldiers, the rehabilitation. And I’m not talking about the Matthew Brady after-battle battlefield photograph style. What I’m referring to is all of the “little” things that happen when the battles aren’t being fought and the troops weren’t on the move. There some images for thing that appeared in Harper’s Weekly and Frank Leslie and so on during the U.S. Civil War, but so far as I can tell the vast majority of them are drawings. Having looked through popular illustrated magazines that covered the Franco-Prussian War, the Spanish American War and all of the conflicts in-between, I just don’t have much of a sense at all that this life was recorded very well photographically.

I can understand this—there’s not that m uch glory in sandbagging Red Cross

stations, or hauling away dead horses by the thousands, or cooking thousands of

loaves of bread in primitive conditions; they certainly aren’t a good case for

a hearts-and-minds campaign. The camera

has enough power to go ‘round, giving and taking, usually at the same

time.

uch glory in sandbagging Red Cross

stations, or hauling away dead horses by the thousands, or cooking thousands of

loaves of bread in primitive conditions; they certainly aren’t a good case for

a hearts-and-minds campaign. The camera

has enough power to go ‘round, giving and taking, usually at the same

time.

But to my brain these photographs really come into being in the second half

of WWI., and they tell an other, integral, more human story of that same war. The first image (above) shows two soldiers

cleaning up cartridge cases after a fight—when you look closely at the photo

you see that the place is littered with those cases. I suspect that there were hundreds of

millions of these cases ejected from rifles.

Billions, probably. I wonder how

long it would take a thousand soldiers to shovel a billion shells into canvas

bags? The picture reveals a very deep

image of the ways of war at the most basic level.

The next photo is a “simple” image of clothing out for a dry—except of

course that the clothing lines go on and on, railroad tracks into the sun,

tended by hundreds of women, getting the shirts ready for the “men in the trenches”, many of whom won’t need those shirts by the

end of the month.

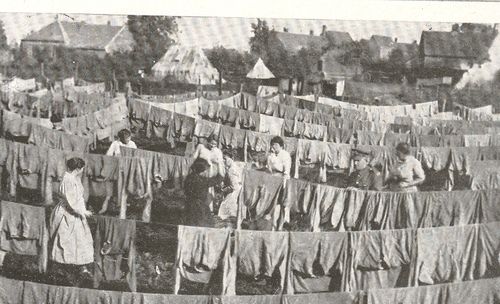

Many of these men and women wound up being consumed--this photo at right shows one of the ways how that happened. It is an extraordinary crater some 75 yards in circumference created by a massive shell. It is a massive image--brutal, lonely, and speaking the quiet of the end. And it was a different sort of image that people were used to seeing in war reporting.

These three photos appeared on only three successive pages of the 15 October 1917 issue of the Illustrated London News.

Posted by John F. Ptak in Militaria, Photography, history | Permalink | Comments (0) | TrackBack (0)

Tags: photography, war photography, World War I

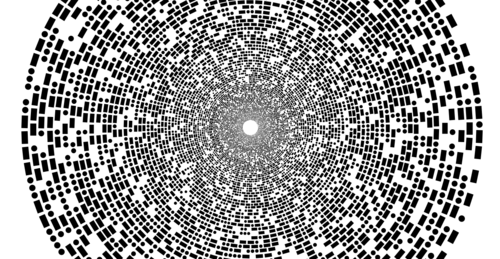

JF Ptak Science Books LLC Post 558

The history of illustration has some distinct phases: from woodcut to wood engraving to engravings on metal to lithography to printing in colors to chromolithography...and then on to a process that would begin to do away with all of those processes, the half-tone. This was a process whose foundation was laid in the 1850's by William Fox Talbot and brought to life in 1873 by Stephen Henry Horgan, though it really wasn't commercially viable until Frederick Ives further deepened the process in 1881, finally becoming a staple in the printing industry in the mid 1890's. The half-tone process would basically due away with the line-centric engraving process, as it was much quicker and easier to use, making images much more readily available to daily-printed media like newspapers. Images that were drawn could be rendered without being engraved; also, one of its greatest advantages was being able to reproduce photographs, which was an enormous breakthrough, as a photograph automatically increased the veracity of the image. (During the U.S. Civil War, reader's of the illustrated

The history of illustration has some distinct phases: from woodcut to wood engraving to engravings on metal to lithography to printing in colors to chromolithography...and then on to a process that would begin to do away with all of those processes, the half-tone. This was a process whose foundation was laid in the 1850's by William Fox Talbot and brought to life in 1873 by Stephen Henry Horgan, though it really wasn't commercially viable until Frederick Ives further deepened the process in 1881, finally becoming a staple in the printing industry in the mid 1890's. The half-tone process would basically due away with the line-centric engraving process, as it was much quicker and easier to use, making images much more readily available to daily-printed media like newspapers. Images that were drawn could be rendered without being engraved; also, one of its greatest advantages was being able to reproduce photographs, which was an enormous breakthrough, as a photograph automatically increased the veracity of the image. (During the U.S. Civil War, reader's of the illustrated

weekly journal Harper's Weekly trusted battlefield images more if the wood engraving appearing in the magazine was copied from a photograph rather than being from the sketchbook of the

correspondent on the scene. The photograph would capture a particular point in time (nearly) instantaneously, whereas the war correspondent artist captured bits and pieces of an instant flavored with memory and subsequent action. The phrase in the credit line. "Drawn from a photograph", had real value.)

And so it came to pass that the happy lives of dots and lines--so important and intertwined in such things as the Morse Code--made a particular and dramatic break with the triumph of the half-tone over the engraving in illustrating popular publications (from the 1890's to the 1980's).

And so it came to pass that the happy lives of dots and lines--so important and intertwined in such things as the Morse Code--made a particular and dramatic break with the triumph of the half-tone over the engraving in illustrating popular publications (from the 1890's to the 1980's).

The image above at left is a magnification of an engraving from 1760;above right is a half-tone image of a 1905 Alfred Stieglitz photo; below left is a magnified sample of what the Stieglitz was composed of; and bottom right finds an illustration of the different combinations in size and color that would effect the composed final image in the final column.

Posted by John F. Ptak in History of Dots, Photography, history, Technology, History of | Permalink | Comments (0) | TrackBack (0)

Tags: half-tone illustration, history of newspaper illustration, Stephen Horgan

JF Ptak Science Books LLC

In my collection of WWI News Photo Service Agency photographs I would say that half or so of them show scenes like this--semi-informal group portraits of military support groups. 500 portraits like this seem to be a lot, and I'm not sure why these images are so well represented. Except of course that there weren't that many images (overall) of active-battle scenes.

These bakers, working at a front-line support station, from my read were probably taking a break, and the photographer took the opportunity to draw them together for the portrait. I don't know why they're separated so, but they do look as though they have a real camaraderie--it is just a wonderful picture, full of friendship and loyalty, and I'm sure it has never been published before.

Posted by John F. Ptak in Militaria, Photography, history, Prints--looking HARD/deeply at | Permalink | Comments (0) | TrackBack (0)

JF Ptak Science Books LLC Post 467

This is another magnificent group portrait from my collection of News Service Photographs from World War I. This is image is from mid-1918 and depicts nurses, wounded and recovering soldiers and an assortment of volunteers preparing relief packages for other wounded soldiers in filed hospitals. My experience with these images is that are many levels of portraits within the larger group portrait--looking at them under magnification is an addictive process, and quite often there are some lovely surprises.

Posted by John F. Ptak in Photography, history, Prints--looking HARD/deeply at | Permalink | Comments (1) | TrackBack (0)

Tags: Photograph, World War I

JF Ptak Science Books LLC Post 465

In

When the end of the War came, so did the appreciation for the women replacement workers—there was bitter feelings in the post-war period because of the weak British economy and a scarcity of jobs. So the women who took the jobs of men to help the country’s war effort and free up hundreds of thousands of men for war service became an atavistic action, “taking” the jobs of men who had gone out to fight for their country. This of course cost many women their jobs, but the damage had already been deeply done to the pre-1914 British world of the sexual politics of business-being-done, though it would take World war Ii to really ingrain the appearance of women in the workforce into the national psyche.

Posted by John F. Ptak in Militaria, Photography, history, Women, History of | Permalink | Comments (0) | TrackBack (0)

Tags: feminism, job equality, Women, women's rights, work history, World War I