JF Ptak Science Books Post 2578

"The truest attraction of "found poetry" is that it should remain lost"-- not Marcel Duchamp

"The highest pleasure in finding poetry is the ability to lose it again"--not Ambrose Bierce

There's a certain identifiable current that runs just beneath the surface of created quotes about found poetry--and I tend to agree, except that I think I enjoy "found poetry" more so than the great majority of poetry-in general, so if I am to read any poetry at all I think that poetry must be found now and then. And the thing about Found Poetry (now capitalized!) is that is can be obscure ("Obscurity is never so clear as when it is never noticed"--not Mark Twain) or so much part of the visual culture that its very unforgivable presence makes it invisible--though I have no doubt that the overt intellectual and traitor E. pound would disagree.

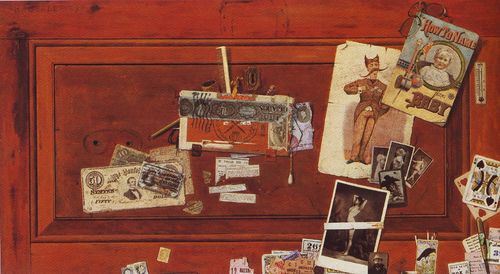

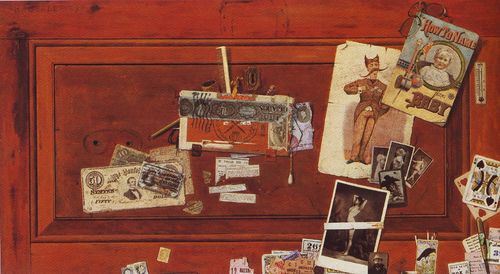

Found Poetry I think has been around for a century or so, finding its roots with the Dadists and the solitary art anti-movement M. Duchamp. And probably an argument could be made for the acoustomatic continuation of another found-hyphenated movement--like Stockhausen/Varese/Xenakis musique concrète--is an outgrowth (or something) of the Found/Readymade embarkation of the nineteen-teens. Maybe too something could be made of the argument that they are all coming from a long and very slow development of trompe l'oeil and Still Life, as there is a definite visual/found quality to many of these works (as with "A Bachelor's Drawer", painted between 1890-1894 by John Haberle).

[Source: Wikimedia]

Still Life images like this of "discovered" assortments of human-created bits, snapshots of unintentional arrangements, must certainly have a sense of Foundness surrounding them. Of course, a pastoral scene of cows-in-a-field or a John Constable sky or some such are necessarily "found" because they are an uncontrollable part of nature--what I'm talking about is a discovered sense of some sort of human construction, and that certainly includes words. (On the other hand, I did write a post "The Found Poetry of the Vocabulary of Clouds" on a John Comenius text of 1726, here: http://longstreet.typepad.com/thesciencebookstore/2015/05/annotated-found-poetry-of-clouds-1726.html.)

So, for today, one part of the concept of Found Poetry I'd like to look at is in the science--in particular, title pages and indexes for works int eh sciences, and in this case the works are historic, though they could easily have been from any odd page in any opened book, anywhere.

The first example is the title page of Galileo's epochal Sidereus Nuncius (1610):

SIDEREAL MESSENGER

unfolding great and very wonderful sights

and displaying to the gaze of everyone,

but especially philosophers and astronomers,

the things that were observed by

GALILEO GALILEI,

Florentine patrician

and public mathematician of the University of Padua,

with the help of a spyglass lately devised by him,

about the face of the Moon, countless fixed stars,

the Milky Way, nebulous stars,

but especially about

four planets

flying around the star of Jupiter at unequal intervals

and periods with wonderful swiftness;

which, unknown by anyone until this day,

the first author detected recently

and decided to name

MEDICEAN STARS

[Full text via internet archive, here: https://archive.org/details/siderealmessenge80gali]

A second example comes from the impossibly accomplished Christian Huygens' Cosmotheoros, The Celestial World Discover'd: or, Conjectures Concerning the Inhabitants, Plants and Productions of the Worlds in the Planets--and it comes from the table of contents: