JF Ptak Science Books LLC Post 555

“Contrive to have as many treats for your mind as you can, as many things to which it can fly from itself” Sam. Johnson. (James Boswell, Ominous Years, pg. 287

Boredom is a powerful thing. It is also, at least as a word if not as a

concept, relatively young—it first appeared in Dicken’s Bleak House in 1852,

with the word bore making an earlier appearance in 1762. (Bitter Ambrose Bierce

redefines “bore” as a person who speaks when you wish them to listen.) Boredom is distinct from Melancholy, which

relates more to depression than to boredom, and is an idea and word thousands

of years old. Boredom is a universal

constant, a wide acknowledged entity of enormous reach and singular acuity—and the

fact of the matter is that you cannot translate boredom into a narrative. You can create art depicting boredom, and you

can tell what boredom is, but you cannot, really, cannot write a novel with a

boredom narrative. Unless you’re Jane

Austen. It is a tired pursuit of

tireless insipidity which simply escapes capture in the form of a novel—or I

should say, a novel that you’d like to read, or was readable. Boredom still awaits its Quixote. Melancholy on the other hand has many, not

the least of which is one of the most unreadable and fascinating books in the

canons of English lit,

Boredom is a powerful thing. It is also, at least as a word if not as a

concept, relatively young—it first appeared in Dicken’s Bleak House in 1852,

with the word bore making an earlier appearance in 1762. (Bitter Ambrose Bierce

redefines “bore” as a person who speaks when you wish them to listen.) Boredom is distinct from Melancholy, which

relates more to depression than to boredom, and is an idea and word thousands

of years old. Boredom is a universal

constant, a wide acknowledged entity of enormous reach and singular acuity—and the

fact of the matter is that you cannot translate boredom into a narrative. You can create art depicting boredom, and you

can tell what boredom is, but you cannot, really, cannot write a novel with a

boredom narrative. Unless you’re Jane

Austen. It is a tired pursuit of

tireless insipidity which simply escapes capture in the form of a novel—or I

should say, a novel that you’d like to read, or was readable. Boredom still awaits its Quixote. Melancholy on the other hand has many, not

the least of which is one of the most unreadable and fascinating books in the

canons of English lit,

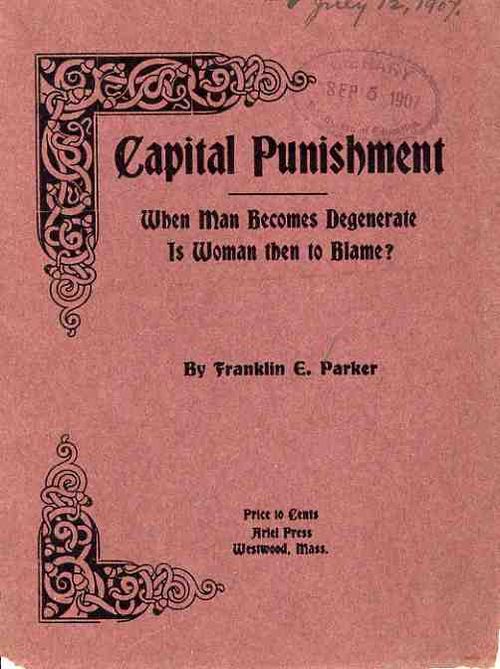

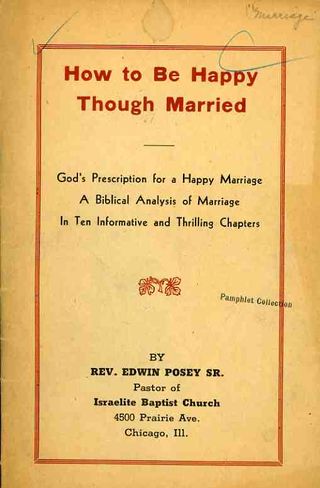

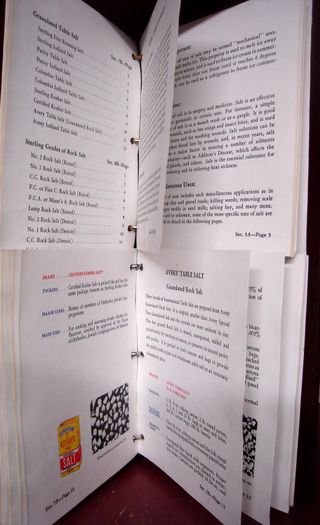

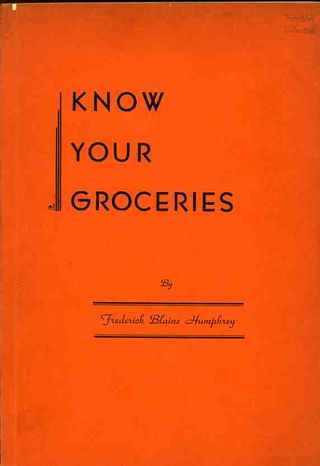

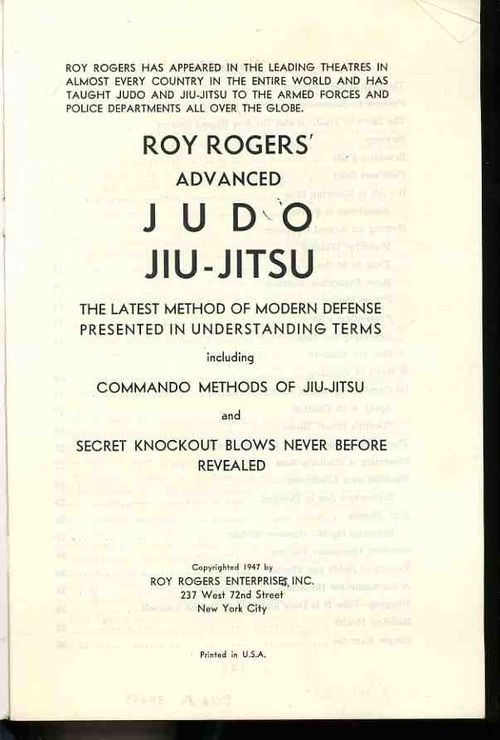

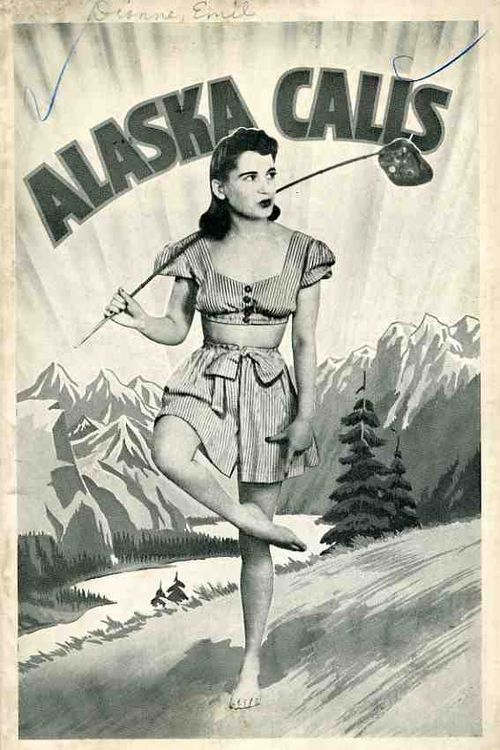

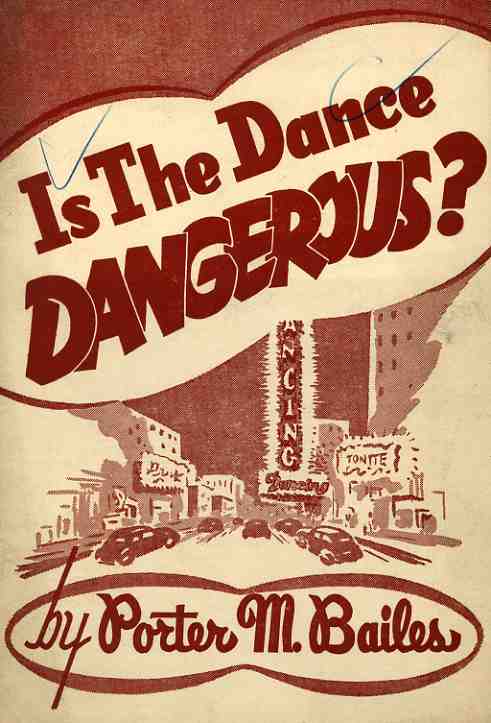

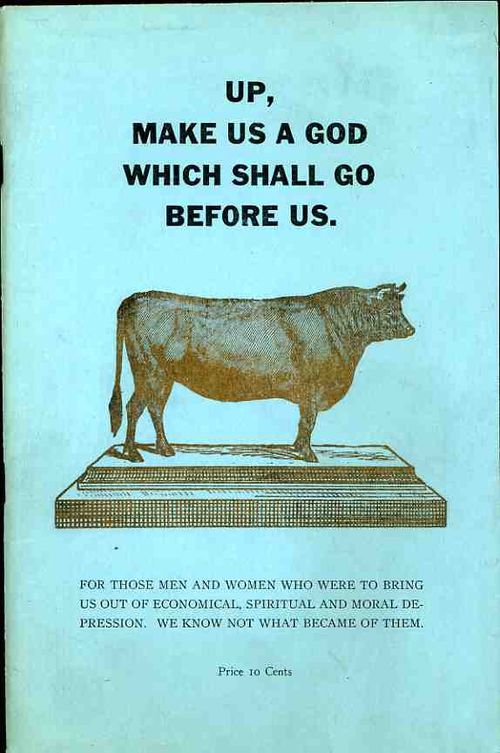

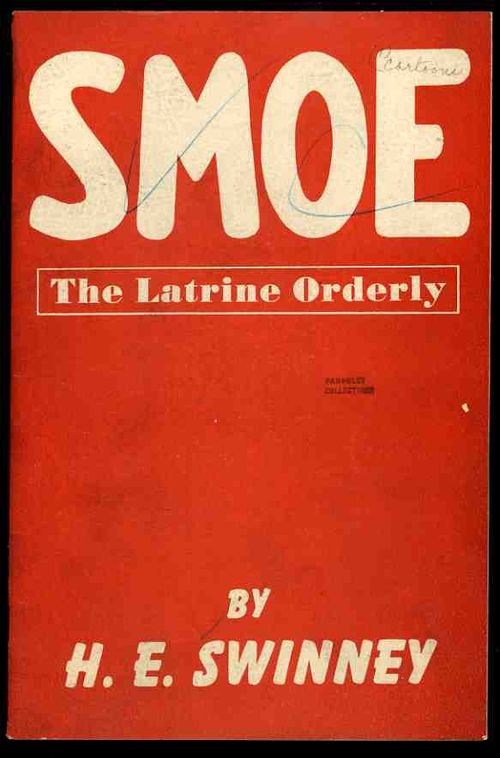

I was thinking about boredom in

terms of some of the printed material in

my Naïve Surreal category—those are the pamphlets where the meanings of their

titles and subjects, once popular in their day, are now aloof and unhinged,

floating in the present with almost no bearing on what their original logical

intent was. And so these titles

sometimes take on a fantastically removed appearance, and sometimes they are

simply simple, so simple that they can be at first blush quite boring. But they’re boring only for a moment, until

the brain wraps itself around the illogic of them, and then they become not

boring—fascinating, someti mes. And what

is that tiny space between the wide widths of boredom and fascination? How microscopic are those pores between the

two entities? And what exactly is that place where boredom and fascination meet?

mes. And what

is that tiny space between the wide widths of boredom and fascination? How microscopic are those pores between the

two entities? And what exactly is that place where boredom and fascination meet?

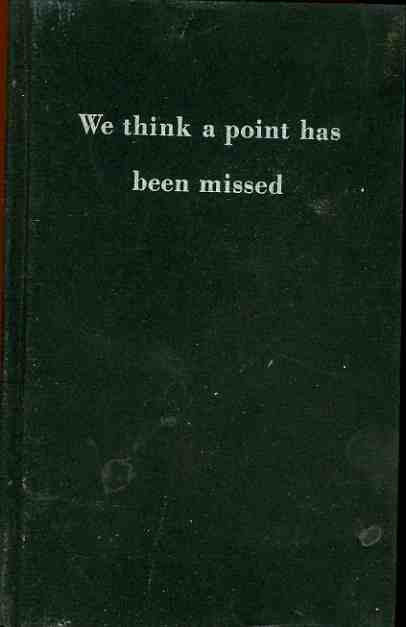

We Think a Point Has Been Missed (published in March, 1933) is an odd example, going from boring to puzzling to incredible to disappointing to interesting all in about a minute. It is a lovely title to be sure, flying at the heights of the sublime mundane, hiding in its own obvious nature. Opening the booklet we find that it was published by the Columbia Broadcasting System, and at first blush it seems a fainting on miniature problems of the naiscent radio company. But it turns out that it is actually fairly topical: CBS wanted to make it very clear that the eight-minute radio broadcast of President Roosevelt on March 4th 1933* was a significant and exceptional use of the new medium, CBS points out that "Roosevelt did advertising's most significant job...advertising 'courage" and "conquered despair", and that those eight minutes over the radio "added cash value of the nation....commodity markets pulsated, dollars rose around the world, demand for department store credit rose 40 percent". In short, this was an early recognition of the extreme value of immediate access to a national population.

The Roosevelt speech, which went without quotation in this short report, was his inaugural address, the day of his taking the reigns from Herbert Hoover--the "All we have to fear is fear itself" speech, which did indeed galvanize the nation, delivered virtually immediately via radio. ("God bless Roosevelt; god bless radio" intoned Will Rogers.) It is one of the country's best inaugural speeches, made at a time when the country needed one, there in the depths of the Great Depression in the late winter of 1933. But all of this is so far down in this slender seven-page book that the speech almost smokily wisps its way through it, the main emphasis being the importance of the delivery system and not the stuff of delivery. Its a queer little thing, all of its importances semi-hidden, made more pronounced in this particular copy since it was owned by Roosevelt.

The second example or boring-interesting is the ultra-under compelling Don't, which when published in 1926 threatened directions for advising improprieties in conduct and common errors of speech. Written by "Censor", it dragged itself through 76 pages of nitty dialog details that are in a way interesting as a window on correct conduct during the roaring times. Ultimately though the text doesn't survive interest, and all we're left with is the very unusual title.

Which takes us back to appearances and second-life and the intersection of boredom and the fantastic. I suspect that if we apply the microscope to that boundary that we see exactly what we want to see.