JF Ptak Science Books Post 305

Stone has preserved the evidences of much of the life on Earth—in the fossil record (which happens to stretch some number of years back before 4004 BCE contrary to what one of the vice presidential candidate believes), or an arrested day in Pompeii; indeed the entire landscape shows the way life looked by filling in the negative of what you see today., a negative landscape in a way of what has come before. The City of Rocks, New Mexico, for example, out there near Silver City, is a wonderful example of trying to employ your imagination to render in your mind the massive volcano that once stood there, the “City” being the last remnant of its existence. Better yet is the great Ship Rock (hello Officer Jim Chee!), a massive 1,800 foot tall fractured volcanic breccia spire in Navajo Land (Tsé Bit'a'í, in Navaho, "rock with wings”), the internal remnant of yet another massive volcano, though in this case the enormous radiating dykes (igneous rock called "minette".) exploding away from its base gives you a better idea of the footprint of the missing mountain. You can see this magnificent mountain from a great distance, and it is only when you start to get closer and drive through one of the dikes (that has been separated for the road) that is 20’ tall and still a long way from the base of the mountain that you get a =good appreciation of just how massive it all is.

I cannot imagine the gargantuan profundity felt by the person who first realized that the Grand Canyon was formed by erosive forces over previously unimaginable long periods of time, its awesome and enormous silence a negative punctuation to the enormity of the idea.

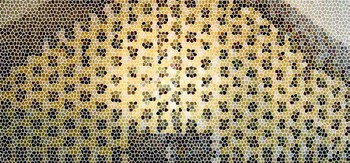

Prior to the major discoveries in geology in the 19th century, say from the mid-18th century and earlier, there were many “discoveries” of life in stone—they weren’t very useful and most often were very misleading, but they were, in two words, pretty and unusual.

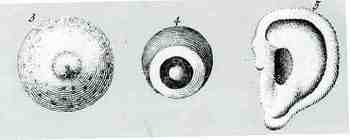

The people who made and recorded these discoveries were often more circumspect about what they were finding than their readers; sometimes not. Jean-Baptise Robinet (1735–1820) was a French naturalist, Jesuit-philosopher and encyclopediaist (best known for his five-volume work De la nature (1761-8)) who found all manner of interesting and scientifically-divergent items in stone—eyes, ears, skulls and occasionally an entire body. Antoine J.D. d’Argenville at about the same time in the 1750’s also uncovered silhouettes of dressed human, birds, cityscapes, trees and the like in stones, which seeped its recordings of the animate into receptive fantasies.

But these durable micro- explorations in agate go back thousands of years, expounded by Pliny and some of the other ancients, who followed the origins of humanity back into the rocks. This was a popular idea for the origin of animate beings, propounding itself for centuries, even winding up in the bony lap of Leibniz of all people, who wrote that “men derive from animals, animals from plants, plants from fossils, which in turn derive from bodies that the senses and imagination represent to us as being totally dead and formless”. Stoners therefore held the seeds of the formation of the world; all things living, breathing, and not.

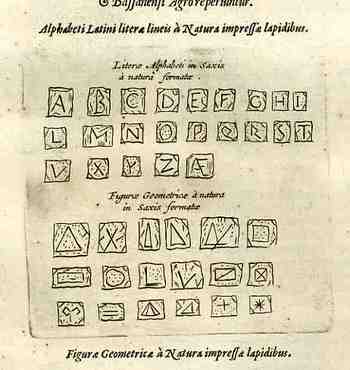

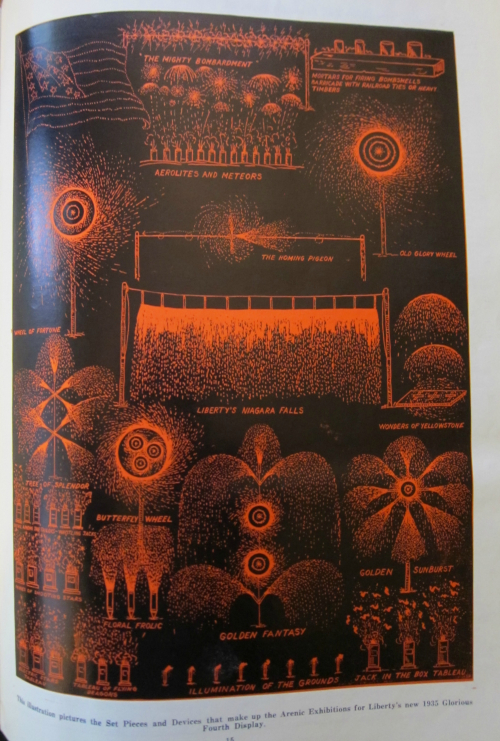

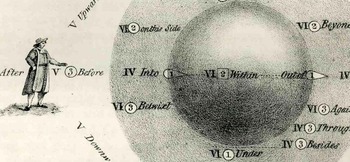

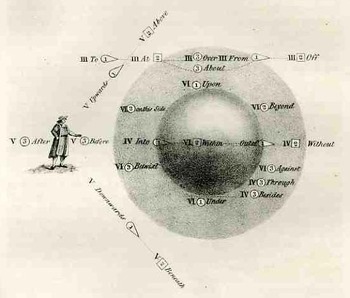

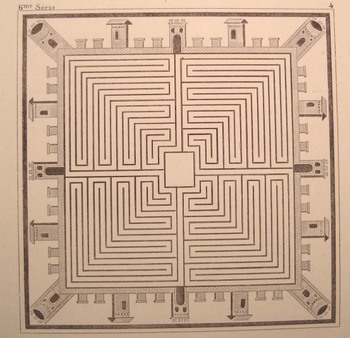

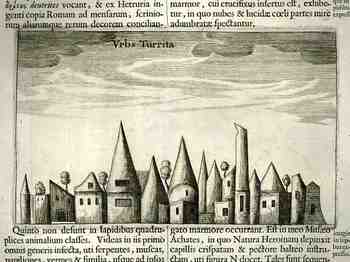

Our own Athanasius Kircher, the definition of Polymathic ability and superior imagination was responsible for many such observations and discoveries. It seems to me that as much as Kircher gave, he took away, keeping ahead of his critics and the rest of the scientific community with tremendous output…people I think just couldn’t keep up with him. He found all sorts of things in stone: as early as 1619 he exhibited an image of St. Jerome (in no less a place than the cave of the Nativity in Bethlehem!) that he found in agate. His Munduis Subterraneus (1661) is ahome to a wide range of these objects: quadrupeds of all shapes and descriptions, human full-length portraits, hands with jewels, and even the Virgin Mary and child. AS spectacular as these are there is always more: the magnificent cityscape (reproduced here) and the sublime discoveries of a full set of the alphabet and a series of 15 geometrical drawings, all naturally impressed in stone.

Perhaps these men gave little more regard to the details in this stone than was necessitated by accepted theory; perhaps they added details to suit their observational needs, as they images were, after all, drawings of the susceptible and the fantastic, and were not photographs. Recording their record was as much open to interpretation as were the theories. I have no doubt that if you look hard enough at things you will at some point find what you are seeking. Only here it is by chance that these figures appeared, and not by the will of a divine creator placing a seed of potential in the stone.

My five-year-old daughter, Tessie, asked me just the other day about where numbers and letters “came from”. She wanted to know “why are they here?”, which is a fabulous question with a long difficult answer. I do know though that they didn’t come to us from agate.