JF Ptak Science Books

A Daily History of Holes, Dots, Lines, Science, History, Math, Physics, Art, the Unintentional Absurd, Architecture, Maps, Data Visualization, Blank and Missing Things, and so on. |1.6 million words, 7500 images, 4.9 million hits| Press & appearances in The Times, Le Figaro, Mensa, The Economist, The Guardian, Discovery News, Slate, Le Monde, Sci American Blogs, Le Point, and many other places... 5000+ total posts since 2008.. Contact johnfptak at gmail dot com

The Invention of Satirical Photography (1840)

JF Ptak Science Books Post 1911

(Image source, Gerry Badger blog, who also has some interesting things to say about the work as momento mori.)

(Image source, Gerry Badger blog, who also has some interesting things to say about the work as momento mori.)The road in determining who was the first person to what discovery is sometime a bit rocky--so with the invention of the computer (ask Mr. Atanatsoff), and the telephone (ditto Mr. Gray) and the television (and so to with Dr. Korn). This is also the case with photography, the rights for the discovery of the process contested in the first year following the announcement of the process.

The response to rejected claims for priority in discovery are almost (?) never recorded visually, but in he case of photography the rejected party did make a visual response, which I think was a prosimentrum of sorts, a photographic novella, and the appearance of the first use of satire in photography.

Louis Daguerre's epochal publication in the Comptes Rendus in 1839 would bring about the general recognition of the birth of photography--his process was described in that article and was immediately set to use by hundreds of adventurers people even in the first few weeks after publication. IT may well be that there are legitimate claimants working on the "photogenic" science before this time but it is Mr. Daguerre who published his findings first.

Among the many "firsts" in the first year of photography (reckoned as PD or post Daguerre

[Source here.]

Generally though the first photographic portrait has been recognized as being the work of Robert Cornelius, who was among the earliest practioners of the new science of the Daguerreotype. This is his work, dated 1839, made in his father's gas light importing business on Chestnut Street, Philadelphia:

![]()

(Both subjects have interesting hair issues.)

is is fine and remarkable, though the images simply record the bodies of the humans that are pictured. The first human portrait with an edge, with a political or social axe too grind and point to make, an image bent on a decisive end, belongs to a man who mildly and then hotly contested Daguerere's claim to the birth of photography--Hippolyte Bayard.

Bayard (1807-1887) experimented in the photographic science before the publication of Daguerre's paper and had shared some of his successes at this early date with members of the French Academy of Sciences (the publishers of the esteemed Comptes Rendus, the vehicle for Daguerre's paper). He was even in communication with Francois Arago, who as it turns out was the champion of Daguerre, and who introduced the paper to the world. After the appearance of Daguerre's paper Bayard--no doubt somewhat envious of the attention and money/funding that Daguerre was receiving) petitioned for help from Arago to establish his own claim and a chance for the experimenter's lament (funding). He was told in no uncertain terms by Arago to cease the attention, as it would hurt the chances of Daguerre to establish his priority and have the honor of the invention of photography to stay in France. It is a longer story than this, obviously, but suffice to say, Bayard's interests were mostly ignored, his priority claims relinquished. (He was later able to collect a few thousand francs for his scientific work, but the larger prizes eluded him.

And so in 1840, full of his own defeat and thoroughly impressed by Daguerre's success, Bayard composed the (above) portrait of himself as a drowned and dead man. On the reverse he wote:

"The corpse which you see here is that of M. Bayard, inventor of the process that has just been shown to you. As far as I know this indefatigable experimenter has been occupied for about three years with his discovery. The Government which has been only too generous to Monsieur Daguerre, has said it can do nothing for Monsieur Bayard, and the poor wretch has drowned himself. Oh the vagaries of human life....! ... He has been at the morgue for several days, and no-one has recognized or claimed him. Ladies and gentlemen, you'd better pass along for fear of offending your sense of smell, for as you can observe, the face and hands of the gentleman are beginning to decay." (From Helmut Gernsheim, A Concise History of Photography, with Alison Gernsheim, London: Thames & Hudson, 1965)

It seems that the use of satire in photography was not common in the first few decades following 1839, which makes Bayard's first use of he genre in 1840 even more remarkable. Satire in general has been aroudn for thousands of years, mostly in the form of drama and literature, and then in (Western, at least) painting in the Renaissance), right up through the Brueghels and Hogarth and Chaplin's Great Dictator and Dr. Strangelove. But it seems to me that the first photographic use of the genre came with the overtaken Bayard, who at least deserves this honor of "firstness".

Note:

I just wanted to remark on the hands and head of Bayard in his self-portrait--I believe that the man is just sunburned. It si common to see in 19th century photographs of working people that--when their hat is removed and so on--we see a big sun/tan line ont heir forehead. This is particularly the case in the work of Solomon Butcher, who recorded the lives of families on the SOdbuster Fronter in the 1880's and 1890's in Nebraska.

(Source, Nebraska State Historical Society.)

Electricity as an Added Lethal Measure to Barbed Wire: World War I

JF Ptak Science Books Quick Post

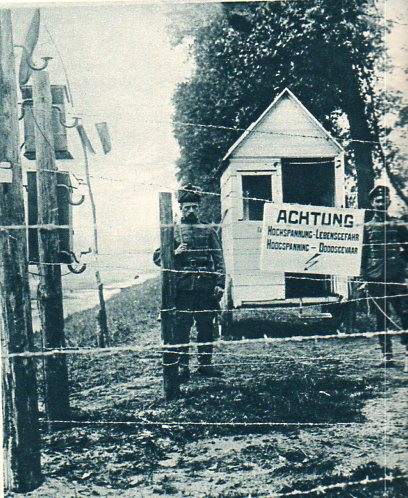

Barbed wire was one of the most successful and horrifying defensive weapons of World War I. In 1915 it was made more effective yet by adding high-voltage electricity to the emplacements. In general the electrical barbed wire fence was employed as only a tiny fraction of all wire fences during the war--as the non-electrified fence was already extremely effective, very cheap to produce and very easily installed--but the possibility of finding an electrified wire somewhere along the lengthy rat's nests of miles and miles of this thing must've had some sort of very major weight in most soldiers' minds.

The following image (and details) from The Illustrated London News for 9 October 1915:

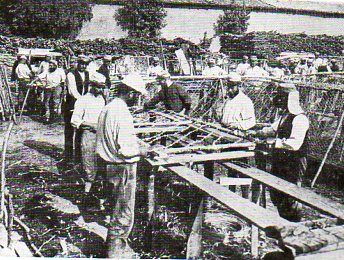

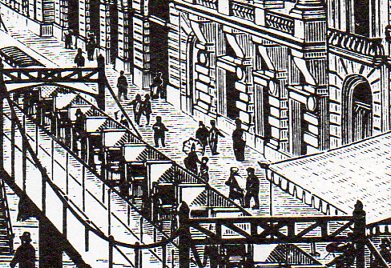

And the places where the barbed wire was made and packaged, again from The Illustrated London News for 16 October 1915.

It looks as though the wire was stretched across 3.5 foot poles, with the barbed wire added diagonally, and then rolled up in long sections for easy transport and deployment.

Posted by John F. Ptak in Bad Ideas, Inventions, Militaria, Technology, History of | Permalink | Comments (0) | TrackBack (0)

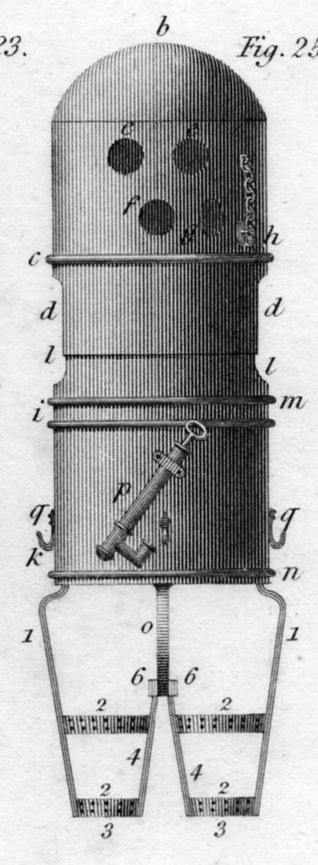

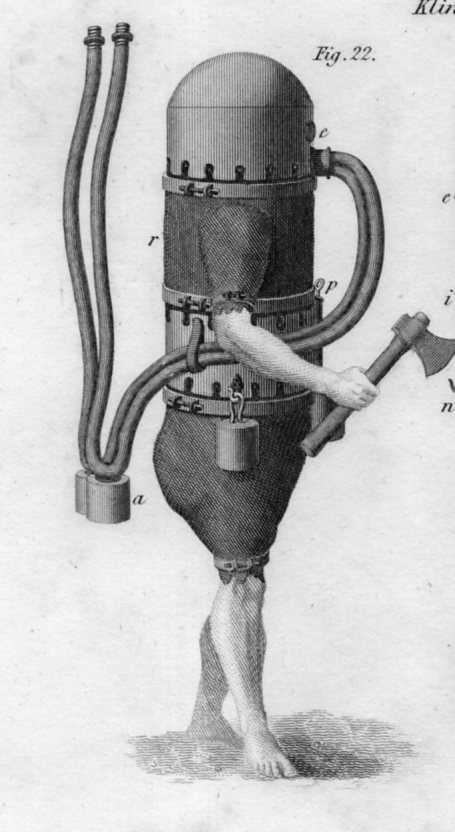

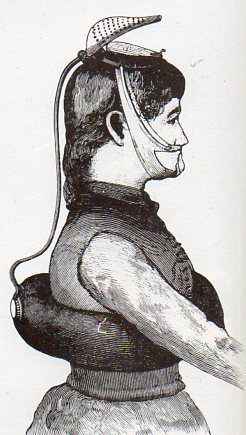

Air-Punk: Underwater Cyborg Diving Suit (1797)

JF Ptak Science Books Post 1853

Well, not really. It is however an early diving suit (and perhaps the earliest apparatus worn on the person and submerged) the creative and comparatively lightweight effort of Karl Heinrich Klingert, who produced it at the very end of the 18th century, in 1797 or thereabouts. The suit was made of a metal helmet and wide metal girdle, with the vest and pants made of a waterproof leather, and with leather (?) leg straps. The air would be pumped down to the diver from a turret above (see below, just) and would arrive in the diver's helmet via weighted air tubes.

Here's a side and occupied view:

Continue reading "Air-Punk: Underwater Cyborg Diving Suit (1797)" »

A Game by Any other Name: Chess as Not-Chess, 1873-1922

JF Ptak Science Books Quick Post [Part of the History of Patents series.]

Looking for (workable) patent models/templates for folding paper chess piece carriers (there are such things) I found these game patents, all of which are based to some degree on chess. I'm not sure why you'd play them if you could simply just play chess, but, well, they do seem like an interesting diversion, though from the little I read on actually playing each of the games they seem somewhat hollow. They are, however, pretty-looking things if not pretty-playing.

Each image is clickable back to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office where there is an accompanying text which sometimes gives enough information so that you could play the game.

Continue reading "A Game by Any other Name: Chess as Not-Chess, 1873-1922" »

Posted by John F. Ptak in Inventions, Patents | Permalink | Comments (0) | TrackBack (0)

Tags: Chess, patent

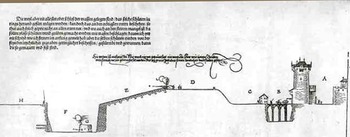

The Atomic Crossbow of Leonardo da Vinci

JF Ptak Science Books Post 1753

Leonardo understood "big", especially when it came to weapons, and he understood what the concept of 'big" meant to adversaries and enemies of the folks with the "big" weapon--a bit of psych-ops in the mid-Renaissance by the High Renaissance man.

Leonardo's crossbow (drawn around 1486) should have worked. He certainly understood the idea of stored power in his many drawings--bent and twisted and torqued wooden arms and such--and the concepts of enormous potential is certainly reeking through-and-through this fantastic weapon. The bow itself seems certainly like a laminated object, adding to its strength via flexibility, the giant bow-string drawn back by a very considerable worm and gear, the whole of which is set to give flight to a large stone more so than an arrow. And that stone was supposed to be able to be delivered to its target over and over again, with minor adjustments, which would have placed it head-and shoulders above cannons, whose recoil made it really quit impossible to re-aim the instrument with any accuracy at the same target over and over again. The main compliment of the crossbow, then, was reproducible accuracies. (In this vein it is interesting to recall "Operation Crossbow", a Combined Bombing Operations during WWII that took place in 1943 and 1944 against the Nazi installations for the V-2 and V-3 weapons--a directed effort to remove a threat which was even more "precise" (if by "precision" we mean marginally guided weapons loaded with high explosives).)

The "atomic" part of the title of this post is I know far from the mark of being metaphorically correct--the scale isn't anywhere near being accurate. Offhand to have an "atomic" crossbow in relation to a nominally normal crossbow in similar scale of the Fat Man weapon in scale with an "average" 500-pound bomb (40 million pounds in relation to 500 pounds) the atomic crossbow would need to be miles wide.

Posted by John F. Ptak in Circles, Geometry, History of the Future, Inventions, Militaria | Permalink | Comments (0) | TrackBack (0)

The Death Ray and Cloud Writing--Battlefield to Breakfast in a Few Short Years.

JF Ptak Science Books Post 1749 [Part of the Strange Things in the Sky department.]

The Death Ray is a long-discussed idea, extending back as far to Archimedes at least--discussed, attempted, abandoned and dismissed. But as a matter of fact, the thing was actually invented, and deployed, though not int he sense of an EM weapon, or LRAD/ultrasonic, or Teller x-ray laser, or even a Wellsian heat ray (below).

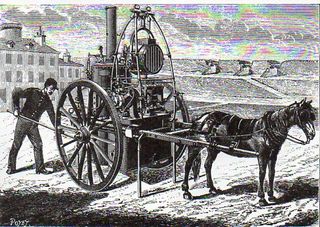

The "Death Ray" made its appearance in the 1880's, but not in the normal sense of what we would today think of as a "weapon"--this death ray could locate the enemy hidden miles from the front, or pick out ships at sea far from shore, and so on, removing stealth capacity, making it possible for these elements to be identified as targets, and then possibly removed, though not by the ray itself.

This "death ray" was the search light. In the 1880's when the technology of electric lighting was still in its first practicable decade, the idea of being able to focus a beam of light from a lantern source hauled on a single-mule carriage and powered by an on-board battery, small steam engine and Gramme dynamo was a spectacular. achievement.

[This image appeared in the Scientific American in 1886 and features what is probably a one-foot diameter mirror, making it capable of illuminating an object up to about a mile away. Something with a three-foot diameter could work its magic on object up to four miles away.]

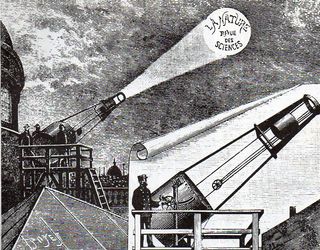

This defensive/offensive weapon/device was very soon afterwards made into a trickle-down appliance that was placed into commercial use almost immediately. The standard use of course would be upgrading lighthouses, but one special use was using a large mirror in a device to project an advertisement on the clouds in a city--ads in the sky.

[Source, La Nature, 1894; also reprinted in Scientific American in the same year.]

[Source, La Nature, 1894; also reprinted in Scientific American in the same year.]

Such a device was used experimentally at the Columbian Exposition in Chicago for the World's Fair of 1893, flashing the daily attendance on the clouds. I'm not sure why the greater revenue-generating employment of this technology took another year to develop. And so "The Death Ray", from Battlefield to Breakfast Cereal in a few short years.

Posted by John F. Ptak in Inventions, Militaria, Strange Things in the Sky, Technology, History of | Permalink | Comments (0) | TrackBack (0)

Steampunk InnerNaughts of the 19th Century

JF Ptak Science Books Post 1743

These creations weren't so much about exploring the innerEarth than they were about surviving in the outermost, shallowest bits of its depth. Survival gear for The Great Unpleasantness in disastrous adventures at sea was relatively scant for hundreds of years, although the nineteenth century did offer a number of new, Victorian technolust attempts for survival-at-sea.

I know that this first contrivance in some of its particular parts looks enormously compromised, but really the stuff attached to the woman's head just allowed her to breathe about 10 inches higher than her mouth, though it seems to me that this air-catcher might catch more water than anything else. Still, it was an interesting attempt at keeping people floating above the water when in peril.

In general though it seems to me that most of the big adventures in wearable life saving devices were big indeed, big and heavy--if there was just a little more room for a small engine, wed' be in the Steampunk realm, as can be seen in this magnificent attempt by T. Beck in his 14 March 1876 patent:

In general though it seems to me that most of the big adventures in wearable life saving devices were big indeed, big and heavy--if there was just a little more room for a small engine, wed' be in the Steampunk realm, as can be seen in this magnificent attempt by T. Beck in his 14 March 1876 patent:

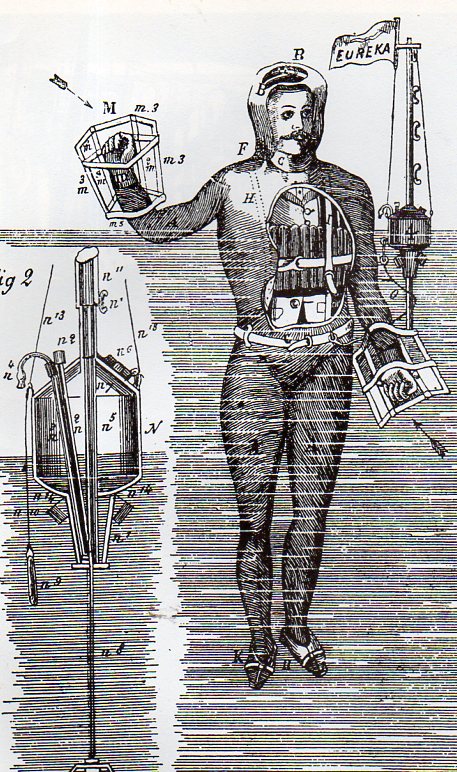

This was somehow an improvement over a more complicated but still more sensible device that appeared earlier in 1869, the work of Captain John Stoner. He exhibited his creation in NYC off the piers in the East River as demonstration of the suit's effectiveness, the whole of which was big news, appearing in the July 17, 1869 issue of Scientific American. The suit was made of rubber, and was insulated and was equipped with a personal buoy which carried a "Eureka" flag and had a compartment filled with food, water, lighting materials, cigars, and of course reading material to help pass the time. The hand-flippers on the other hand look like a very good idea.

A more streamlined idea of the Stoner suit appeared in F. Weck's patent application of 24 October 1876, again using a rubber suit, but this time the safety device was far less cumbersome, and equipped with little more than an interesting-looking breathing apparatus connected to a towed buoy which of course flew the American flag.

Since I mentioned the possibility of cigars in the above-mentioned case, I should also point out that it took several decades for someone to patent a waterproof case for swimming with cigarettes, "in case the swimmer wanted to swim out to some rocks and then relax with a cigarette".

G. & C. Palmer came forward with another unusual idea in their 11 November 1873 patent, using chess-like figures to pus their idea of an expanding/collapsing life preserver vest, which would move in rhythm with ocean waves and theoretically protect the wearer from being overcome by bad swells. I have my extended doubts about this one.

Most of the patent applications that I've looked at tonight seem to lake one critical element--locomotion. Of course they're assuming that the life vest is doing little more than keeping the wearer from drowning (though sometimes comforted with cigars and flags). A. McDonald went a little further with his invention (patented 17 January 1882) by putting a screw propeller on the belly of his life vest. It all looks very heavy and sinkable.

F. Vaughan continued on the idea of a big, heavy wetsuit preserver by making his even bigger and heavier. This 1879 creation looks to have about 10 inches (or more) or rubber in the suit, which means that if the thing wasn't water-tight, and that if even a very slight leak developed, the wearer would no doubt sink like a stone.

A. Traub (in 1875) created something that was much less bulky and more accessible, a sort of unfolding life vest, that seems really not to do much of anything, but which was at least light:

E.H. Brown (in 1884) had a somewhat different approach to the "life-saving" idea, turning the survival bit into a bucolic if ungainly adventure/romp device for the vacationer on the coast--the "hammock canoe":

Though as cumbersome as this device seems it is quite in step with its contemporaries, at least so far as in being not-very-usable goes:

And somewhere in all of this was the occasional good-looking idea that evidently got caught in the undertow of the heavier/punkier outfits--but in them you can see the beginning of the idea that would eventually work:

Posted by John F. Ptak in Absurdist, Unintentional, Inventions, Technology, History of | Permalink | Comments (0) | TrackBack (0)

Blank, Empty and Missing Things: Stone and Wood

JF Ptak Science Books Post 1742 [Part of the series on Blank, Empty and Missing Things.]

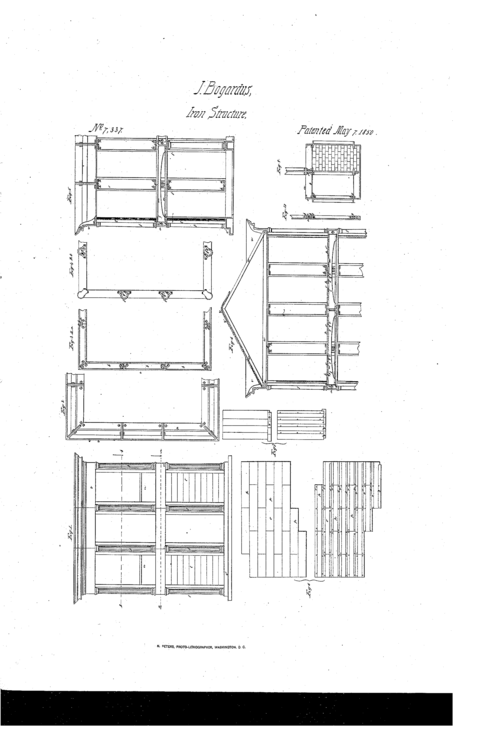

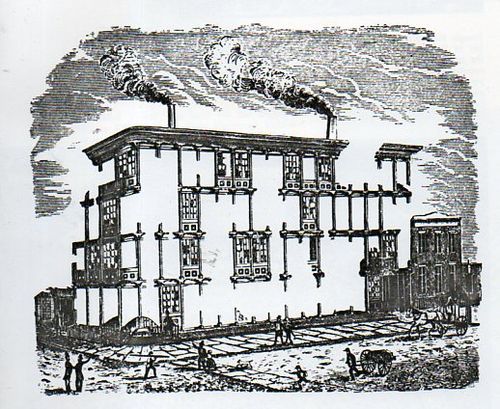

This short post is about this remarkable illustration from a 16-page pamphlet by the inventor, architect and cast tion pioneer James Bogardus (1800-1874, Cast Iron Buildings, their Construction and Advantages, 1856 and 1858 second edition).

But before I get to that, I started to wonder about why it was that NYC developed up rather than out, vertically rather than horizontally? There was plenty of room for outward growth--and in mid-1850's, the period that this post addresses, most of the city had already been laid out, or at least up to 96th street. But in the city of about 900,000 people, there were few people living that far north (and not that many structure), with half of the population living below 42nd street. So, the largely flat, largely unoccupied island could well have been developed northward rather than skyward. My feeling is that the reason for vertical development was "running". That in the pre-telephone days and the earliest days of electrical telegraphy, that in order to conduct business rapidly messengers were used to take documents and communication back and forth. And so for the sake of speed of business, rather than have messengers traveling for 20 or 40 or 80 minutes to a more-removed uptown location, that it made more business sense to keep businesses together; and to do that on limited land, one needed to go up. Not out. I've never thought about this, ever, but this seems to make sense to me...

Now, getting back to the Bogardus illustration: what was missing was the building, or the pieces of the building that had previously been thought of as being absolutely essential for a structure of this size to maintain itself. But what Bogardus had done was to figure out a way of using cast iron rather than other building materials--a building tool that was stronger and with greater engineering chops than anything else that had been previously seen, which meant that there were different forces at play in structures using it, and which meant therefore that even though there were large pieces of the building's shell that were "missing", that this structure could and would still stand. It was a fabulous way of communicating a new idea.

What happened with the Boagardus idea is that it developed into the use of steel-framed buildings, which made for very light, very strong structures, which led to skyscrapers, which led to modernity.

The Harper Brothers building (built in 1854 at 331 Pearl Street) was an iron-facade building that was engineered by Bogardus (with the architect John B. Corlies) and was built in response--and partially as a safe, fire-proof building--following the devastating fire (and enormous liability payout) in the previous Harper building. One thing that was certainly different in the face of this building--owing to the efficiency of the cast iron, there could be plenty of windows in place of where there used to be building materials. And there was certainly plenty of glass in the Harper building.

[Patent source: the very easily usable Google Patents, much more nimble than the UST&PO, somehow.]

The trip to modernity didn't necessarily start here with Bogardus of course, but he was a considerable and significant chunk in the engineering developments necessary for the construction of tall buildings...and here it is interesting to note that another big piece of that development that came into being at nearly the same time (1854) as the publication of Bogardus' pamphlet and the construction of the Harper building was the installation of Otis' safety elevator int eh Haughtwout (five storey) store. And of course the elevator was necessary for the creation of tall buildings, just as the invention of the braking systems was essential for the creation of the elevator. And on the story goes.

The Bogardus achievement (patented May 7, 1850) was certainly an important step--it was pragmatic, efficient, and strong, and also led to the possibility of mass production and pre-fabricated structural elements. And for the mid-1850's, this was certainly a big deal.

One of the few remaining Bogardus structures, at 254 Canal Street, today:

And the Bogardus monument in the famous Green-Wood Cemetery, in Brooklyn:

Posted by John F. Ptak in Architecture and Building, Blank and Empty Things; A History of, Inventions, Patents, Technology, History of | Permalink | Comments (1)

Tags: Architecture, Bogardus, Iron structure, New York City, skyscrapers

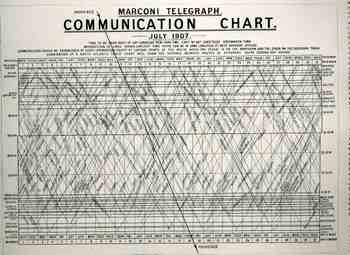

Complicated Simplicity: A Marconi Wireless Graph of Connections at Sea, 1907

JF Ptak Science Books Quick Post

This is an illustration of the approximate times and places that ships at sea could expect to be able to communication with each other by the relatively new invention of wireless telegraphy. (We're talking about Marconi here and just very briefly; this is not the place for the discussion of what he did or didn't "borrow" from his predecessors and contemporaries such as Heinrich Hertz, Oliver Lodge and Nikolai Tesla. He at the very least however owed all of them at least an enormous helping of gratitude, and probably more. Then there's Marconi's very conservative technical continuation in the field which is confusing and interesting. And finally but not the least of all of the stuff about Marconi is his comfort and support of the Fascist regime in Italy, where Marconi became a member in 1923, escalating in his fame through the party ranks to have none other than Benito Mussolini serve as the best man in his second wedding. But as I said that's all for another day.) It appeared in The Illustrated London News for 7 September 1907,surrounded by an article on Obelia in the "Science Jottings" section of the magazine. This chart isn't

quite as complicated as it seems, really: all you need to do is follow one line from the top to the bottom. Simply put, each diagonal line represents a specific ship (all of which are named) and their positions as they make their ways across the North Atlantic ocean; each intersection represents the time and place that two ships can communicate via wireless with one another. So, for example, the Empress of Britain will on its six-day voyage be able to communicate at least 26 times with other ships for news and information.

What this seems to me to be is the supplemental efforts of the ocean-going ships

to the newly established trans-Atlantic radio-telegraphic company and installation opened by Marconi in October 1907. Even though the first transatlantic communication is celebrated as having taken place in 1901, the performance, even in 1907, was still spotty.

Again, I'm just after this for the image

Posted by John F. Ptak in Industrial & Technological art, Information, Quantitative Display of, Inventions | Permalink | Comments (0) | TrackBack (0)

Tags: communication, Fascism, Marconi, Mussolini, wireless

Tech-Quiz #4--the Sublime Mundane

JF Ptak Science Books Quick Post

This forms the absolute end of something, the "tip" of it, one of two, at the either end of slender cord. Even for this there must be a patent--and there were, evidently, many of them. This is just one, from 1922

Answer in the continued reading section, below:

Posted by John F. Ptak in Inventions, Patents, Tech-Quiz | Permalink | Comments (0) | TrackBack (0)

A Curious Episode in the History of Sitting--Speed Chairs & Trainless Trains

JF Ptak Science Books Quick Post

It may be that the history of human locomotion is the story of fast sitting. Except for some of the earliest incarnations of powered movement, it seems one of the most significant engineering aspects moving a person forward is how that person should be carried in the vehicle. And, well, it seems that in the vast majority of cases, the person is sitting. (There are of course exceptions, notably in say the standing of the engineer in the Tom Thumb when that locomotive set the land speed record;or the Wright Brothers' powered aircraft, where the pilot was laying down; or say in a chariot powered by a team of horses. Even in some of the earliest versions of steam-powered tractors, the mammoths were steered by a standing operator. It seems though that in very quick order the operator in most of these vehicles find themselves in a seated position.)

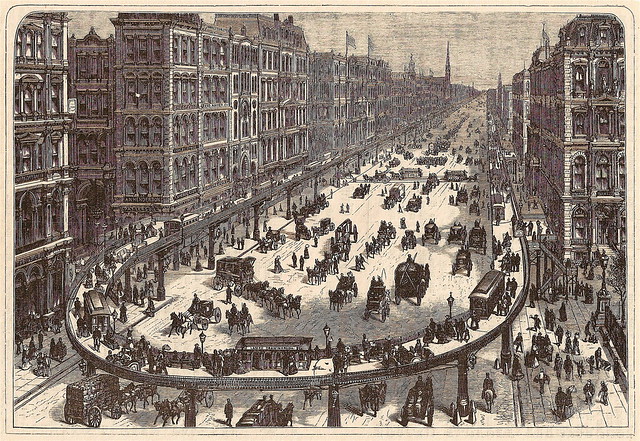

A very curious application of moving seated humans is seen in this woodcut of a chaired walkway--for all intents and purposes, the pedestrians looking to use the moving sidewalk would have been offered a chair instead. It seems as though as its base that this was a very simple form of an elevated subway or trolley, though without the train.

The moving seated sidewalk was the dreamchild of Alfred Speer (1823-1910), of Passaic, New Jersey, and it seems as though it might have been the first form of mass rapid transit in the city for which it was intended, which was NYC. It stood fairly high in the opinions of some prominent New Yorkers (like Horace Greeley and Peter Cooper) when it was presented in the early 1870's, and even passed the New York State Legislature in an act authorizing funding for the program in 1873 and 1874--but it was each time vetoed by Governor John Dix, and the people-moving dream ended there, right before the Centennial. (See here for the New York Times obituary for Speer., and see All Ways NY blog for a longer look at Speer's moving sidewalk, here.)

Here's another version of Speer's idea, though this look more like a moving sidewalk, complete with trolley cars, all of which were stationary objects located on the moving walkway. The idea of course was to free up the chaos and gridlock of the very busy areas of Broadway by placing a large chunk of the confusion on a moving second floor. It seems as though it might have been a good half-year idea or so, and the $3.7 million dollar price tag might've been a hefty one if you calculated the cost per minute of relieved traffic.

[Picture source: All Ways NY.]

Mr. Speer seems to have let his vision go and settled down to a life of wine making.

Three Great First F’s: Forks, Forts, Fission, (and one plain non-first F (Nobel))

JF Ptak Science Books Post 1645

Apropos of nothing whatsoever, I’d like to look at four “first” F’s. the first is the first known published image of a fork , or forcina in Italian. This was a prickish utensil (seen in the image at the bottom-right), hiding none of its stabbing qualities with a middle tine, and shows for us all its direct decent from Mother Knife. It appears in the Opera dell'arte del cucinare by the great Renaissance chef and cook to Pope Pius V Bartolomeo Scappi (c. 1500 – 13 April 1577, buried in the church of SS. Vincenzo ad Anastasio alla Regola, dedicated to cooks and bakers) was published in 1573.

In the book he lists approximately 1000 recipes of the Renaissance cuisine (some of which, for Renaissance salads, appear at bottom) includes many images of kitchenware, the fork being perhaps the most famous. (I used to know the first time that a fork appeared in a painting--of the Last Supper of course, but I've forgotten, though it does come right on the heals of Scappi.)

The second unrelated but interesting first “F” is perhaps the first image of a modern, canon-proofed fort, by none other than Albrecht Durer. This image appears in 1527 in his Etliche underricht zu bestestigung der Stat, Schloss und Flecken, and although his designs were impracticable (massive and massively expensive forts and fortified cities; pretty but very costly), there were certain elements of the work that were very useful—namely, the new face of some of te walls that he offered to the modern canons of the 1520’s. These weapons were vast improvements over their earlier brethren, and Durer responded to the extra and more accurate firepower by lowering and thickening the walls and giving them greater slope—this would aid in deflecting many of the shots that were not directly spot-on, and also would improve the chances of the fort’s survival against those hits by having thicker walls.

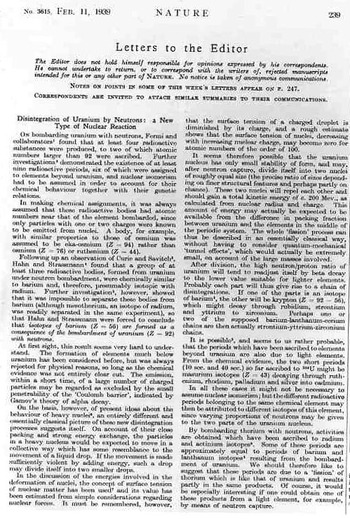

The third F is slightly related to Durer’s fort walls—this is the first appearance of the word “fission”. It appeared as so many of these sorts of 20th century announcements appeared with great sotto voce--this one, in a “Letter to the Editor” of the journal Nature (11 February 1939), by Lise Meitner and Otto Frisch.

The communication, “Disintegration of Uranium by Neutrons: a New Type of Nuclear Reaction” wasn’t a letter to the editor in the conventional sense of course but was meant to be the quickest line of communication of an important result and thus appeared somewhat truncated though the great stuff of the announcement was made known and understood. Niels Bohr’s “The Mechanism of Nuclear Fission” in the Physical Review (1 September 1939) may I think be the first use of “fission” in the title of a paper.)

There is a very big story here with Meitner and fission and Nazis and the Nobel. This leads to our fourth F: and that would be “F” as in “Failure” to the Nobel committee who in 1944 awarded the Nobel Prize to (German, non-Jewish) Otto Hahn for the discovery of nuclear fission while completely ignoring (purposefully, I would say) Meitner, who really, by all rights, should’ve gotten the award, and probably by herself. This is a more complex tale than I would care to deal with now, but I think that it is beyond doubt that the Nobel committee again (think Einstein and others) severely screwed this up in favor of maintaining their dislike for people with Meitner’s heritage. (And yes, she was Jewish; Einstein suffered too at the hands of the committee, not receiving his award, unbelievably, until 1921, *16 years* following what was probably the best single year that anyone ever had in the history of physics, ever, and then 14 years following his great year of 1907 and five years following 1916’s paper. And so on.) Yes, Meitner hung on in a not-good way in Germany for six bad years 1933-1938) until she finally get the hell out, but that really doesn’t tell the story very much. The fission bit with Hahn and Strassmann is a little bedeviling, but it really was Meitner who recognized the whole thing as being the process of fission. Period. And shame again on the Nobel people for getting it wrong, again, on purpose.

Posted by John F. Ptak in Anticipation, History of , Inventions | Permalink | Comments (0) | TrackBack (0)

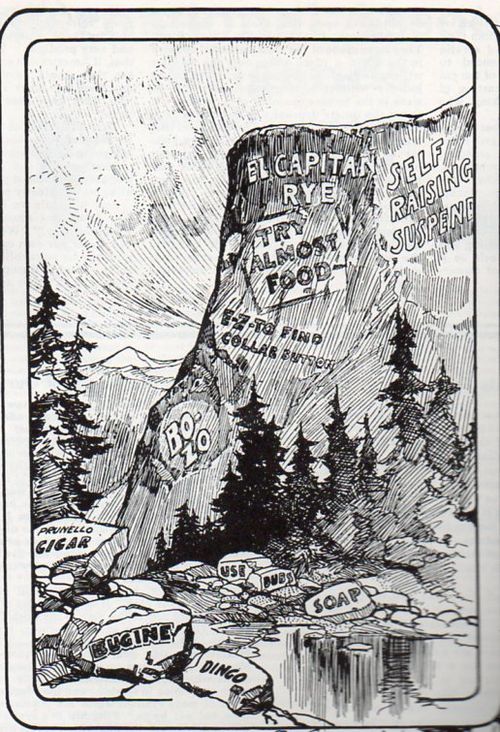

History of the Future--Advertising in Yellowstone, 1905

JF Ptak Science Books Quick Post

The way of the new world, the spread of commercialism and of consumerism, the increase in the size of a middle class that was actually approaching what we today would think of as a middle class, the wanting rise of places for disposable income to go from millions of new people with spare money to spend, led the sellers of stuff-immemorial to start advertising their bits on the side of out-of-doors everything. The fight for the attention span of the new consumer went from the newspapers and magazines to the side of buildings and then, as the motor car began to proliferate, to thousands of miles of roadway.

But when these cartoons appeared in (the first) Life magazine in 1905, the car was still a distant image so far as common ownership was concerned, so the competition for the visual space of the new buying market was center on outdoor displays wherever people might happen to be outdoors. (Remember, there's no radio or television to absorb advert money and viewer attention, so efforts were magnified on billboards.)

So Life took a peep into the future and didn't like what it saw: the possible vast expansion of ugliness in the pursuit of whatever dollar might fall out of whatever pocket. Just a little warning to America is all--the future of the country might not look as pretty it used to be, what with millions of new billboards to place.

The future Niagra Falls, five years hence:

Mark Twain: Bra and Blank Book Patenter

JF Ptak Science Books Quick Post

Samuel Clemens (1835-1910), who became Mark Twain in 1863 and then mostly stayed that way, had a great mind and was a superb writer and story teller--he wasn't necessarily a great inventor, however. In the ear;y sea of his great achievements, in 1871--just after the publication of his first real best-seller, Innocents Abroad, 1869)--Clemens applied for and was granted a patent for a bra clasp. I don't know if it is the bra clasp, or not, but for whatever reason Clemens pursued this interest all the way to the end.

In the year after the publication of Roughing It, and three years before the publication of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Clemens patented--essentially--a blank book. It was a special book/holder for the very-popular practice of scrap booking, and it seems rather ironic that someone who filled up so many books with words would get a patent for the sale of books that didn't have any. Curious.

Posted by John F. Ptak in Absurdist, Unintentional, Inventions, Technology, History of | Permalink | Comments (0) | TrackBack (0)

Recent Posts

- On Getting "E=mc^2" Wrong, Twice in 1.5 Square Inches

- Colossus in the Colosseum

- Birds and Human Flight

- Cross-Section of an Arctic-Exploring Balloon, 1890

- The Goubet Submarine, 1886

- A Monumental and Fantastically Bad Idea: Lowering the Mediterranean (1929)

- Two Uncommon Crowd Scenes, 1932 and 1945.

- Mathematical Exercises and Found Art

- Bridges Never Built: the Hudson River Bridge (Midtown) 1896

- An Episode in Antiquarian Depiction of Upside Down Things (1506)

Categories

- Absurdist, Unintentional (726)

- Alphabets (68)

- American History: Western Exploration & Native Americans (60)

- Anticipation, History of (407)

- Architecture and Building (239)

- Art (54)

- Art History (342)

- Astronomy (162)

- Atlas of Dead Ideas (36)

- Atomic and Nuclear weapons (181)

- Aviation & flight (296)

- Bad Ideas (504)

- Beautiful books (31)

- Biology (12)

- Blank and Empty Things; A History of (362)

- Books--Great Cover Art (57)

- Books--title pages, beautiful (35)

- Books: Great & Lost in the Dust (25)

- Books: Title Pages, Unusual (31)

- Boredom, History of (11)

- Brevity and Complexity (51)

- Calculating (59)

- Chemistry, history of (16)

- Children's Art (23)

- Circles, Geometry (6)

- Color & its advanced Abuses (31)

- Color Theory (33)

- Computer Tech/History (130)

- Contraries (11)

- Cross-Sections (51)

- Daily Dose from Dr. Odd (84)

- Economics (8)

- Electro-LUXurious (21)

- Exploration (3)

- Fantastic Beasts and Tales (9)

- Fantastic Titles (45)

- Fear, History of (21)

- Future Punk (27)

- Future, History of the (312)

- German Design (14)

- Histories of Smallness (30)

- History (2)

- History of Dots (72)

- History of Goodbye (61)

- History of Holes (68)

- History of Lines (83)

- History of Memory (32)

- History of Nothing (47)

- History of the Future (346)

- How Fast Stuff Is. (3)

- Iconography (80)

- Imaginary and Impossible, Museum of the (14)

- Impossible Books (35)

- Industrial & Technological art (171)

- Information, Quantitative Display of (618)

- Inventions (66)

- Lines, History of (36)

- Literature (2)

- Magnifcent Mundane (14)

- Manuscripts (6)

- Maps, Cartography, History of Mapmaking (250)

- Maps/Diagrams of Imagination & Ideas (174)

- mathematics, logic (111)

- Medicine, History of (180)

- Memory, Historry of (12)

- Militaria (476)

- Mistakes, The Importance of (7)

- Music (12)

- Mythology (14)

- Naming Things (147)

- Outsider Logic (98)

- Patents (59)

- Perception (187)

- Perspective (199)

- Photography (144)

- Photography, history (69)

- Physics (115)

- Picture Post/Image Dump (5)

- Piles, History of (1)

- Politics, American (3)

- Poster Series (5)

- Prints--looking HARD/deeply at (279)

- Propaganda (55)

- Psychology (20)

- Questionable Quidity (26)

- Reference Tools (39)

- Science (7)

- Social History (292)

- Sports (5)

- Statistics--Fossil, Found, Odd, Forgotten (29)

- Strange Things in the Sky (41)

- Tech-Quiz (15)

- Technology, History of (838)

- Title Page Art, Beautiful (32)

- Travel (3)

- What is It? (14)

- Women, History of (98)

- WORD art (15)

- World War I (247)

- World War II (56)

- Writing Systems (8)

- You Are There (6)

- Zoomology (25)