JF Ptak Science Books Post 2059

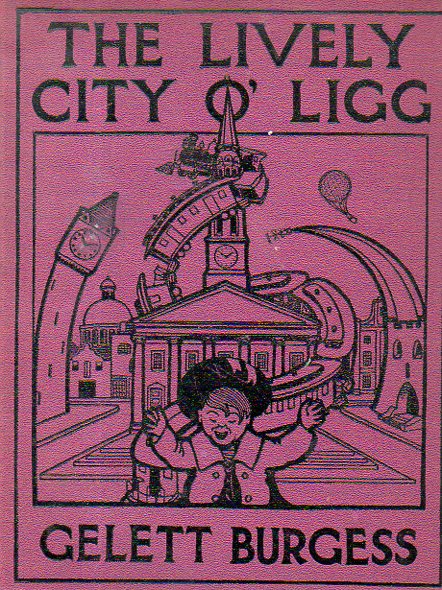

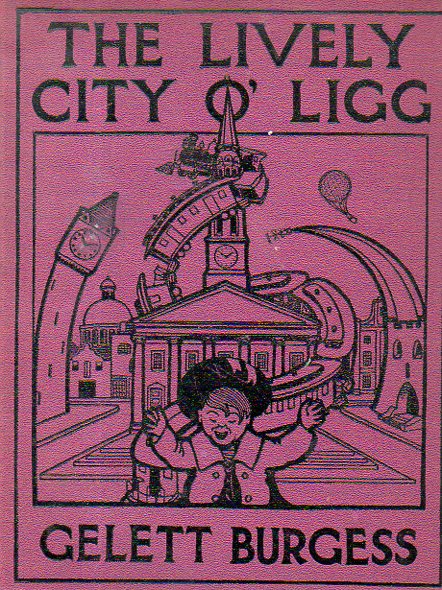

Gelett Burgess (1866-1951, a Boston high-ground MIT grad poet/critic/all-around lit figure who wrote a lot and created an important Little Magazine called The Lark) continued his work in humor and nonsense and future-vision with his The Lively City O'Ligg, a Cycle of Modern Fairy Tales for City Children, in 1899. There's a lot in this squarish book to suggest itself as a sort of farcical-absurdist tomorrow's retro-vision fiction--its only his second book, and not the work he is most famous for, and it was written for the amusement of kids, but really for kids of all ages, and very funny. (Full text here via Internet Archive and prettier edition here via Hathi Trust.)

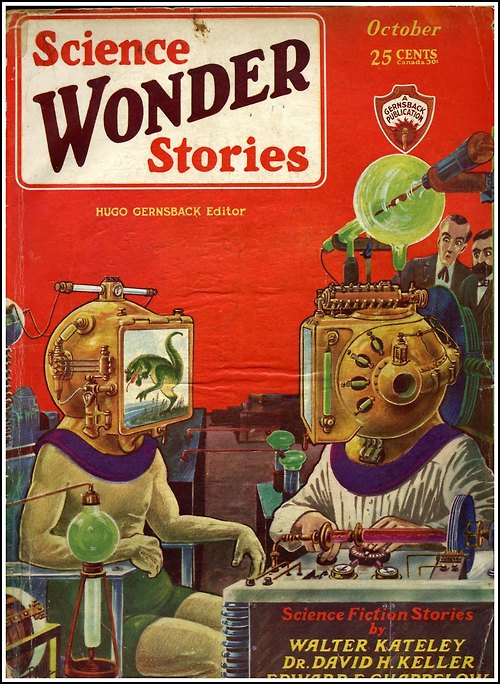

And it has great illustrations. For example, the front cover artwork (for the edition here) suggests a dimension of space/landscape and how it changes as a moving body viewing that scene approaches the speed of light--this is Burgess' art, and it is amazingly prescient of the modern art that was fast approaching in the next decade or so, only Burgess' name isn't very commonly associated with the precursors of displaying the fourth dimension in art. [He is there, though with early associations with Stieglitz at 291 and Max Weber. When I think of these early names it is generally of the more-obscure but very early W. Stringham in his "Regular Figures in n-Dimensional Space", published in 1880, followed by the great Jouffret in his geometries of four-space (published in the 1900-1905 or so), and then of course Charles Howard Hinton and the hyperspace philosophy of Claude Bragdon, followed by H.P. Manning's Geometry of Four Dimensions in 1914. But in between Jouffret and Manning there is also the artwork of Picasso and Braque and Metzinger Gleizes and Le Fauccionier and Gris and Kupka and Duchamp, all of whom addressed this issue of space and time and the fourth dimensions in their work, seminal pieces all and created between 1909-1912. Burgess himself came to the attention of the Stieglitz group by 1910 or so and was given an exhibition of his watercolors at 291 in 1911.)

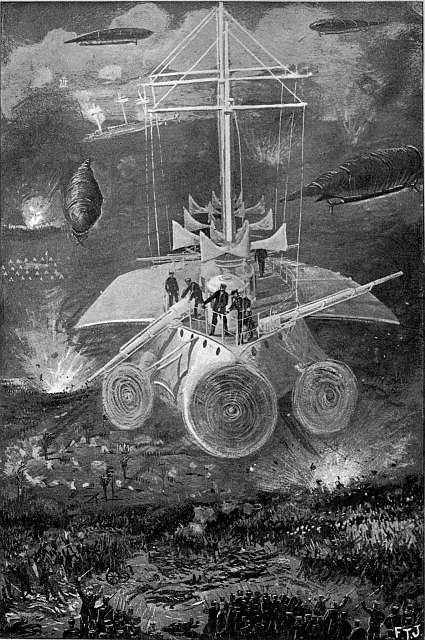

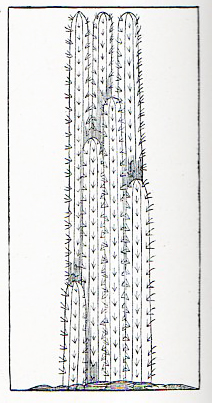

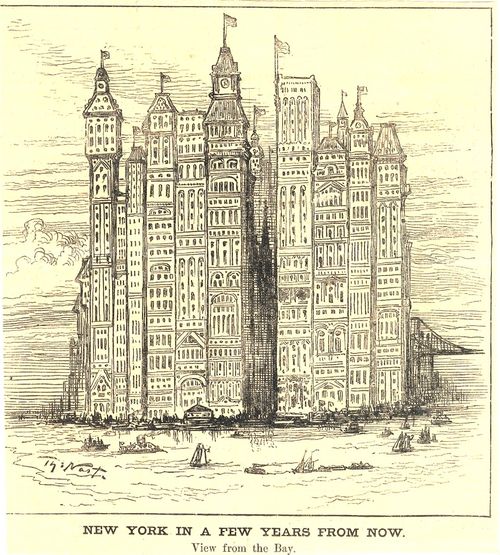

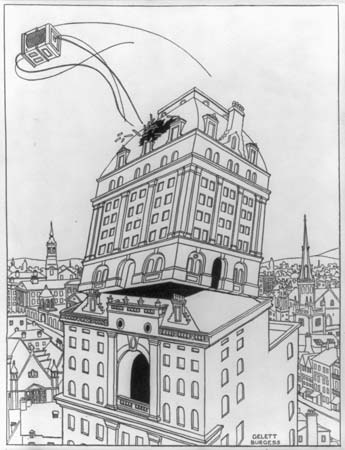

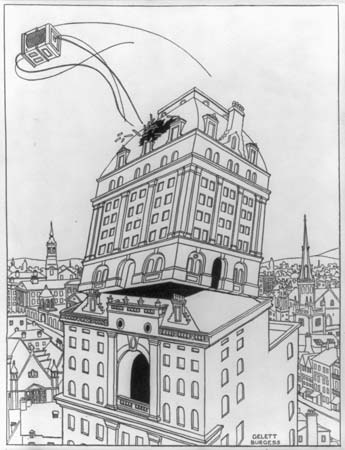

The image illustrating the chapter three, "The Three Elevators" (above), just shows one of them bursting through the roof of an "immense building in the City of o'Ligg" "Twenty-seven stories high (!)". (At the time the world's tallest building wasn't in O'Ligg but in NYC: in 1890, it was the New York World Building, New York City (309 feet, from 16 to 26 stories, but that is another story; closer to the time of the Burgess book it was the

Manhattan Life Insurance Building, again in New York City which was 18 stories and 348 feet high. So the Burgess building was a big one by world standards in 1899--and of course there would be no tall structures like this without steel framing, or elevators, or for that matter fool-proof elevator emergency brakes. In any event the elevator spikes through the roof of the o'Ligg building, looking for all the world like one of the aliens from Wells' War of the Worlds, which was published a year earlier than this book, in 1898. (I should say the appearance was suggested by the first edition of Wells' 1898 book, as it was not illustrated.)

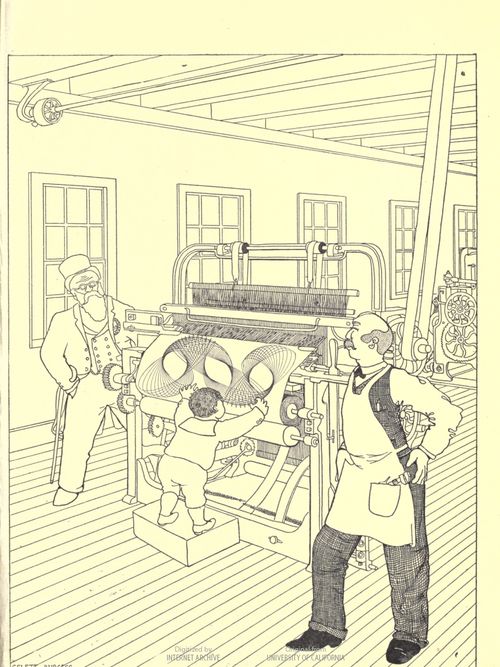

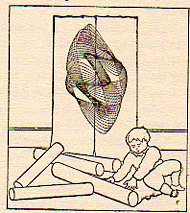

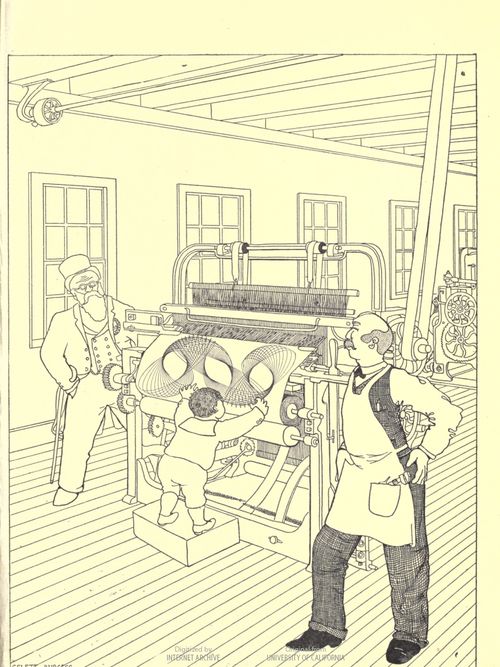

Another surprising example of found-modern art occurs in the final chapter, "The Eccentric Loom", when loom No. 7--like the other machines and implements in these stories--has a mind of its own and produces "something queer", a "crazy design" producing an "insane tapestry". The loom is "either crazy", or "it is a mighty clever machine; altogether too clever for me". But the design as an intentional piece of art for 1899 is pretty extraordinary--and the underlying premise, that the machine might be producing the art on its own, is exceptional and early.

To put the artwork in a more machine-creative-context, here's teh Burgess image that starts off the "Insane Loom" chapter:

There's much more in the Burgess book to discuss, particularly in the anthropomorphization of objects, as in the chapters dealing with a sleepwalking house, the boldness of a balloon, the laziness of o'Ligg lampposts, a flying stable, runaway chairs, and the like1. It is very enjoyable to watch Burgess breathe life into these objects, and give them personalities and lives. But it is a true joy to see him present some of the objects as the "artist" and not just the tool, as we see here in the opening paragraph of the chapter "The Blind Camera":

"THERE were many Cameras living in the Ligg Photo-

graphic Parlours, artists who looked down with scorn upon

all other machines, not only upon the manufacturing

or working members of the community, but upon such

aristocrats as the Bicycles and Balloons as well. The

musical instruments they recognized as artists, it is true,

but it was the Cameras' opinion that most musical instru-

ments were a bit mad. Even the Very Grand Pianos

often got out of tune ; and, besides, they were all totally

blind, from the Penny Whistles to the Church Organs.

The Cameras themselves were deaf and dumb, but they

never thought of that, as they had the best eyes of all

the objects in the City o' Ligg, except the Telescopes,

and the Telescopes didn't count ; they were not artists-

they were merely elaborate tools."

Perhaps our future Robot Overlords (a phrase taken from Mr. Eugene Krabs in

Spongebob Squarepants) will one day in the future look backwards and find

the beginning recognitions of the creative souls of machines in the work of

Mr. Burgess.

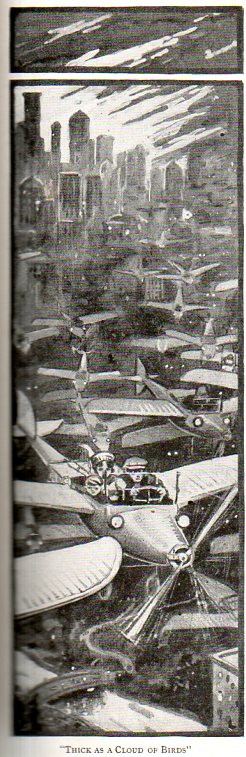

![[34754tutfgjdgdf.jpg]](https://lh6.ggpht.com/_hVOW2U7K4-M/ST2rP9fpFfI/AAAAAAAAugY/u95RIMSHH9g/s1600/34754tutfgjdgdf.jpg)

![[tow_1940summer.jpg]](https://lh5.ggpht.com/abramsv/R4fcwUKUlTI/AAAAAAAADBI/Xu7s8ESZMyM/s1600/tow_1940summer.jpg)