JF Ptak Science Books Post 712 (from 2011, extended, with a full text scan of Children Who Work in the Nation's Crops by Gertrude Folks Zimand, National Child Labor Committee, 1939.)

“The history of childhood is a nightmare from which we have only recently begun to awaken…” Lloyd Demause

"Give me other mothers and I will give you a better world." St. Augustine, (who does not mention fathers in this context).

The history of kindness to children is a wicked road to tread—I’m not sure why I’m even thinking about it had I the subject not been awakened by bumping into the map seen below. Without any real directed reading on the topic I’ve intuitively felt that “childhood” as an idea, as a part of human development in the Western world, was a young, newish innovation. The simplest way to perhaps measure this is looking for representations of children as children in Medieval and Renaissance art—that is to say children drawn not as little/miniature adults, but drawn as children actually appear. This does not happen very much at all in the early Renaissance, and virtually never happens in the Medieval. Even when looking for images of Christ as a baby in early art it is far more likely to find him depicted as a little man than it is to see him as a child. Children certainly seem to make more appearances as themselves in book illustration (excepting the obvious works on anatomy and childbirth) beginning in the early 16th century, and I’ve a number of reproductions here of children with learning-to-walk walkers and toys from this period. So at the very least the recognition of the concept of difference in very very young adults as “children” in art took a much longer (and unexpected at least to me) time to develop as a concept. And this is only the barest concept, at least recognizing childhood as a stage of development, which doesn’t necessarily say anything about the aspect of kindnesses expressed to them simply because of this stature. That’s an entirely different story.

One way to measure this aspect of childhood--the history of kindness towards children--is in terms of how much work society allowed them to perform in the adult world—and again, it would be shown that it was discovered only recently. As an issue of moral and responsibility, child labor was regulated first in England in a long series of Factory Acts (13 separate acts from 1819 to 1961, including 1819, 1831, 1833, 1844, 1847, 1850, 1874, 1878, 1891, 1901, 1937, 1959, 1961) . That first breathe of morality and responsibility towards happiness (where happiness means not being exploited) codified that children younger than nine were not allowed to work, and that kids between the ages of 9 and 18 could only work up to 72 hours in a six-day week1. Children were used freely and copiously for work in fields, in chimneys, in mines, and in tough bugger places that couldn’t be reached by full-grown adults, as well as in places that could use little hands, or suspended in places where a lightweight helper could be slung, and so on.

Historically speaking, controlling children seems to have been the major part of dealing with a child: from controlling its body function (with enemas and such), to movement (swaddling to completely restrict motion), to crying (dunking a crying infant in a pail of ice cold water to stop it from crying),and to mood (feeding fussy children liquor and opiates to make it docile. ) The severe beating of children was the great "other" option in dealing with all manner of childhood issues, the thorny crown of behavior modification. On this point Lloyd Demause in his “The Evolution of Childhood” examines 2000 statements of advice on child rearing prior to the 18th century and found that most advocated severe beatings. He noted that the severity of the beatings was common and “a regular part of the child’s life.” The instruments of behavior advocacy here included “whips of all kinds, the cat o’nine tails, shovels, iron and wooden rods, bundles of sticks, the discipline—a whip made of small chains--, and special school instruments like the flapper, made to induce raising blisters.” (Demause, page 41.) Rousseau—hardly alone among the great philosophers—advocated whippings and beatings from infancy; plenty of the great social thinkers from this period and earlier had little use or accommodation for children, even their own.

There’s also the controlling of the mind via images and fear and promise of retribution of hell, as well as the introduction of spooks, ghosts, goblins and other sorts of child-stealers and –eaters. You’d think that the rough and tough and pretty scary stories of Brothers Grimm would be enough, but it doesn’t come close to the really scary guys: Mormo, Canida, Poine, Sybaris, Acco, Empuss, Gorgon, Ephiatles and others were brought in to do the job of control that spanking and beating and hell couldn’t modify.

Then there’s the sexual misconduct and abuse, which was evidently deep and well practiced for thousands of years, with older Roman men and Athenian rent-a-boy being famous examples of something wider and established. Just from reading a bit through some of the standard histories of childhood it is very easy to see the vast amount of sanctioned abuse that seems to constitute one of society's many sorely soft and cancerous underbellies.

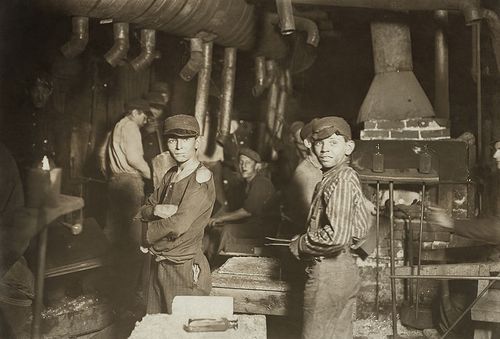

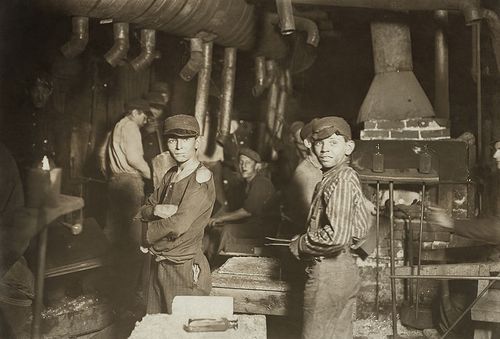

Returning to child labor, for most people in the United States the grotesque nature of this activity was finally revealed to the great masses through the work of the legendary photographer Lewis Hine, whose documentary images of the conditions of children and the laboring classes was an extraordinary dose of reality. It took the unimpeachable foundation of the photograph to hammer home to people that children were being subjected to rigorous labor abuse. (The photo above shows children working in a glass factory at midnight.)

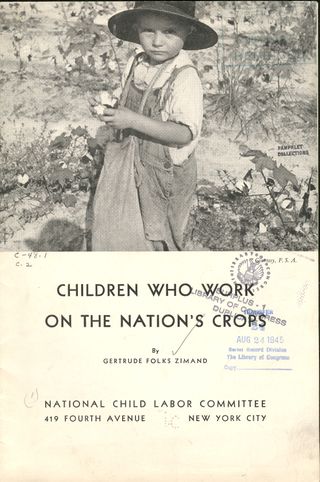

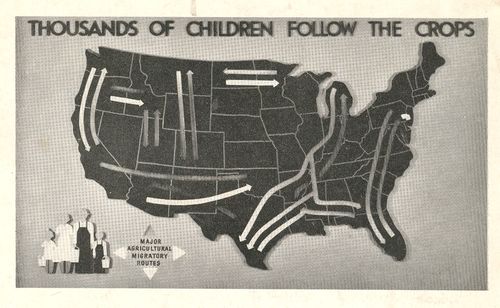

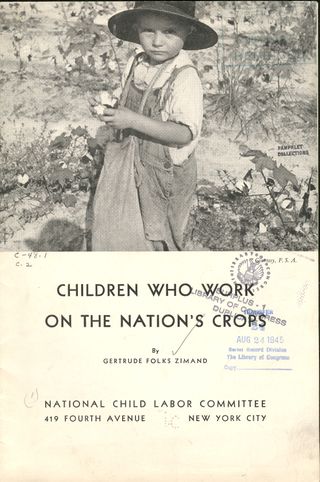

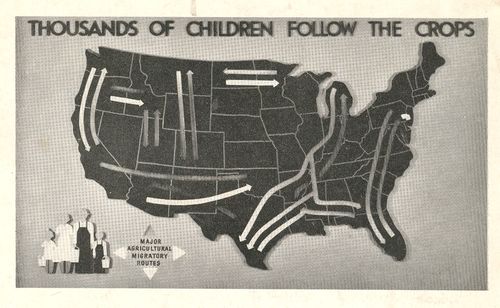

But Factory Acts and Lewis Hine et alia made only incremental change in the exploitation of the very young--evidently economies large and small were addicted to the idea. Which brings us to the map that started this thought: it appeared on the back cover of Children Who Work in the Nation's Crops, written by Gertrude Folks Zimand, and published by the National Child Labor Committee (NCLC) in 1940. The map on the back cover shows the migration routes of the young workers:

There's no surprise to what the map showed, though it was a surprise to see the map itself. The NCLC is still around, and so are the children working in the fields. The map has stayed pretty much the same.

The rest of the pamphlet does not pamper the brittle semi-hidden world of the child laborer. I've included the entire work, below.

UNICEF states that there are still hundreds of millions of children being worked illegally throughout the world, and I can't help but wonder who it is that assembles those free Happy Meals toys (watch that copyright!) which are purchased in the millions for a penny or so apiece. When things like that are as cheap as they are, as impossibly cheap as they are, there must be someone, somewhere, paying the price.

NOTES:

1. The high points (taken from Wiki) of the Factory Act of 1833 stated:

- Children (ages 14–18) must not work more than 12 hours a day with an hour lunch break. Note that this enabled employers to run two 'shifts' of child labour each working day in order to employ their adult male workers for longer.

- Children (ages 9–13) must not work more than 8 hours with an hour lunch break.

- Children (ages 9–13) must have two hours of education per day.

- Outlawed the employment of children under 9 in the textile industry.

- Children under 18 must not work at night.

- provided for routine inspections of factories.

Also, good reads on the history of childhood:

G. Rattray Taylor, The Angel Makers

David Hunt, Parents and Children in History

George Payne, The Child in Human Progress

Philippe Aries, Centuries of Childhood

and

Lloyd Demause,editor, The History of Childhood.

Children Who Work in the Nation's Crops

by Gertrude Folks Zimand, National Child Labor Committee, New York City January 1942