JF Ptak Science Books LLC Post 561

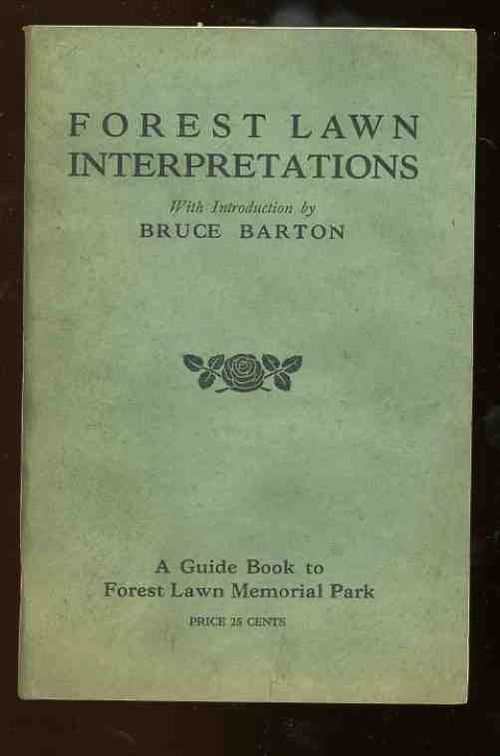

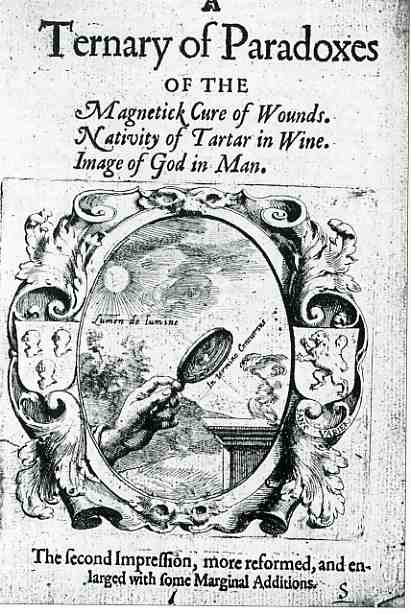

This is another in a series of posts on the Sublime Mundane--books and pamphlets whose titles are nothing if not introductions to spectacular nothingness. Sometimes these publications are indeed about disappearing wisps of lost lint, and sometimes not; sometimes the mundane and seemingly stupifyingly "normality" of their subject matter leads to something of deep depth. Today's pamphlet, left, fits the second category.

Part of the interest in this work--outside of its momentarily arresting title that has a potential for being a cascade of boredom-- is that it so quickly rights itself into an important topic. That's not to say that it isn't a boring topic, as my quick and semi-feeble research reveals. It does get interesting though when you consider that it took so long for the recognition that, since all of these children in school have been brought together, that there wasn't some sort of federally organized effort to make sure that the weakest members of this group had at least one decent meal a day. That said, the earliest program were for students who could afford to pay for their lunches. Perhaps it was assumed that, around the turn of the century, there were no lunch rooms per se and that children would eat wherever they could find the space, that many children were also going home for lunch, and that they were all being fed. (I do remember that some classmates of mine in P.S. 29 would go home for lunch, and I remember wondering exactly what that was all about. I can recall taking my brother for special every-so-often-Friday treats at Joe & Pat's Pizzeria for three slices and two cokes for a dollar back there in 1968. But I digress.) It actually took a little time before children's lunches at school were made to be free to those who needed it.

Which brings us to Marion Nestle's Food Politics (Berkeley, University

of California Press, 2002), who discusses the early commodification of children's food: "School meal programs

began during the Great Depression of the 1930's. From

the outset, they had two purposes: to help dispose of

surplus agricultural commodities owned by the government

as a result of price-support agreement with farmers ,

and to help prevent nutritional deficiencies among low-income

schoolchildren. Because chronic disease risk factors were

not an issue at that time, the rules specified meals that

used surplus commodities and were higher in fat, saturated

fat, sugar, and salt---and lower in fiber---than recommended

in later years." All of which is detestable and unwholesome and immediately transparent.

Perhaps the really interesting stuff on feeding children at school starts here, in the 1930's, and that with the commercialization of children's biological needs, breaking the back of an agricultural finance  problem in the school lunch rooms. The lunch as commodity expands from massive leftover projects into something a little more insidious in the television age, when children not only get to dress their foods in the sorts of containers that they wanted (lunch boxes), but also were being deluged with displays of foods that they could select for themselves via television. This commercialization process gets ramped up decade by decade, until in the 1990's and 2000's the lunchroom has in some cases become an extension of the t.v. commercial, and that local and state governments are counting the value of sugary waters, salt, and catchup packets while plying the rest of the arrested nutritional package with prepackaged conglomerate goodness.

problem in the school lunch rooms. The lunch as commodity expands from massive leftover projects into something a little more insidious in the television age, when children not only get to dress their foods in the sorts of containers that they wanted (lunch boxes), but also were being deluged with displays of foods that they could select for themselves via television. This commercialization process gets ramped up decade by decade, until in the 1990's and 2000's the lunchroom has in some cases become an extension of the t.v. commercial, and that local and state governments are counting the value of sugary waters, salt, and catchup packets while plying the rest of the arrested nutritional package with prepackaged conglomerate goodness.

And such is the value of the sublime mundane, at least for me--these items are filled with possibilities invisible to their titles.

Even after all of this, I must confess that I would dearly like to have a Fireball XL5 lunch box to take with me into eternity. All systems go!

Some interesting links with more than you need to know about school lunch history:

The Food Museum Online Exhibit: School Lunch History

School Lunch Programs in the USA (according to city)

School Lunch Programs in Europe