JF Ptak Science Books Post 1209

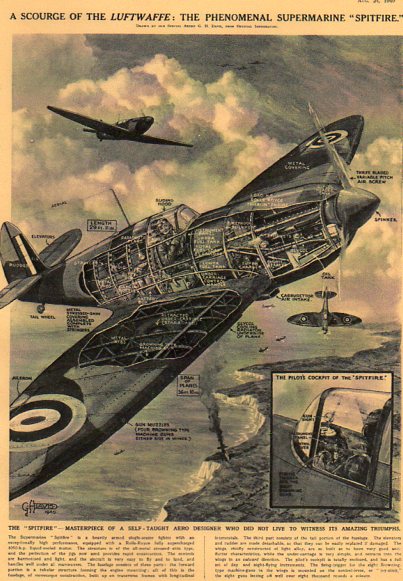

Aerial bombing from heavier-than-aircraft comes to a big anniversary soon, on 1 November 2011, a century after the Italian Lt. Giulio Cavotti dropped the first bomb from a plane on oasis-encamped Libyan troops at Tripoli. Of course things rapidly in the few years following that, so that by the end of WWI people got a good taste of what it meant to controlling pieces of property without actually occupying them, raining chaos and destruction from

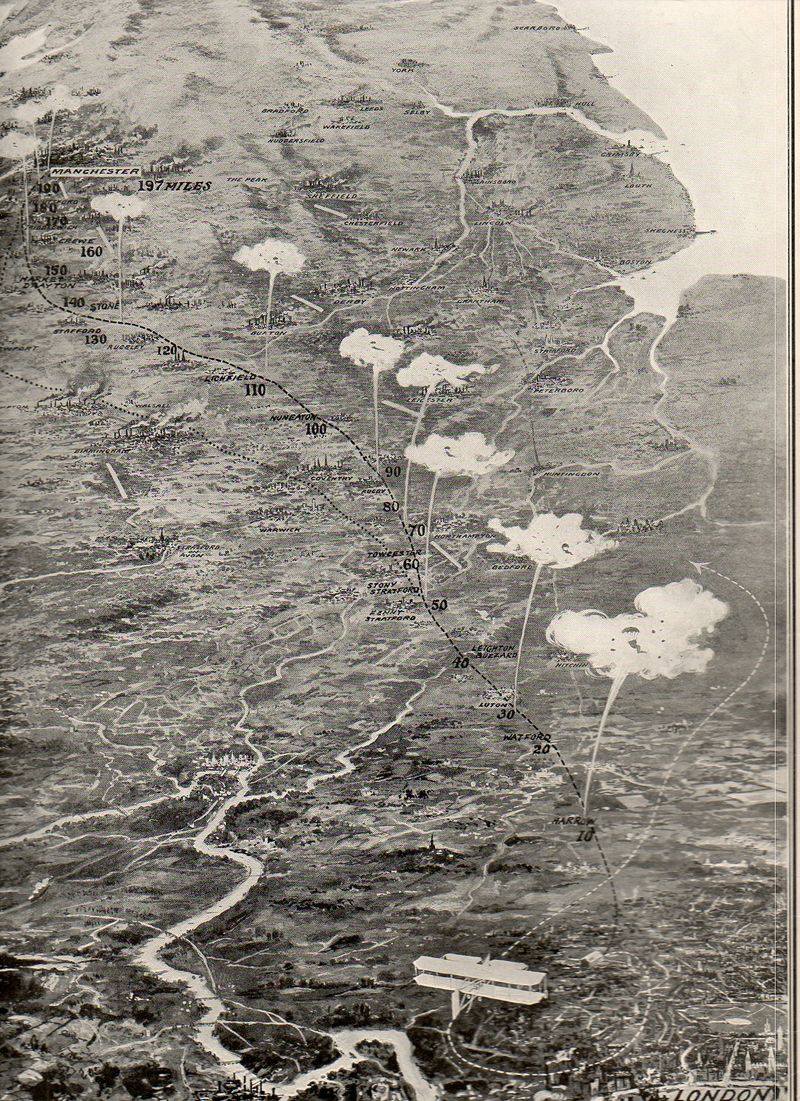

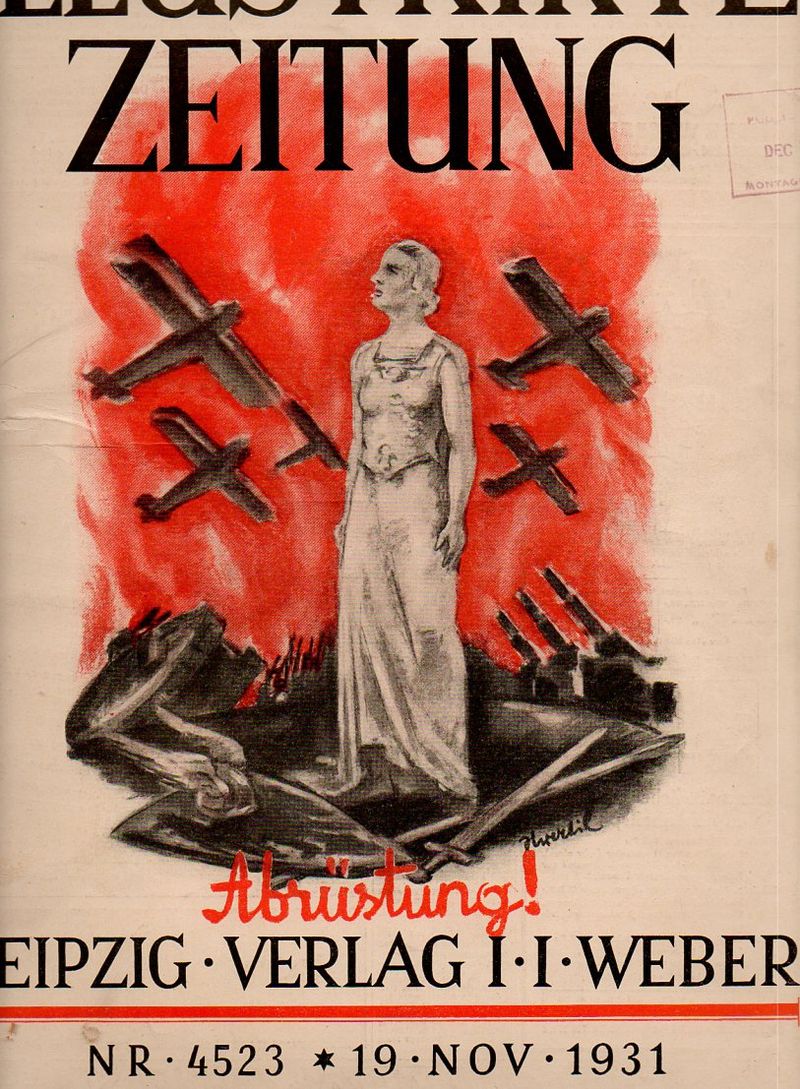

above. 20+ years later, in the early 1930's bombing became more sophisticated, including a new arsenal of poison gas weapons. The threat from this weapon was agonizing and palpable–the results of gas attacks upon armed combatants in WWI and the gassing of civilians in the 1920's and early 1930's made a hard strike into the social fabric, an enormous gapping new hole to be filled in the heart of fear. [And of course this fear was felt everywhere, from London to New York to Leipzig to Moscow to Milan, as we can see in these few examples below. ALSO: these images may be purchased rfom our blog bookstore, here.]

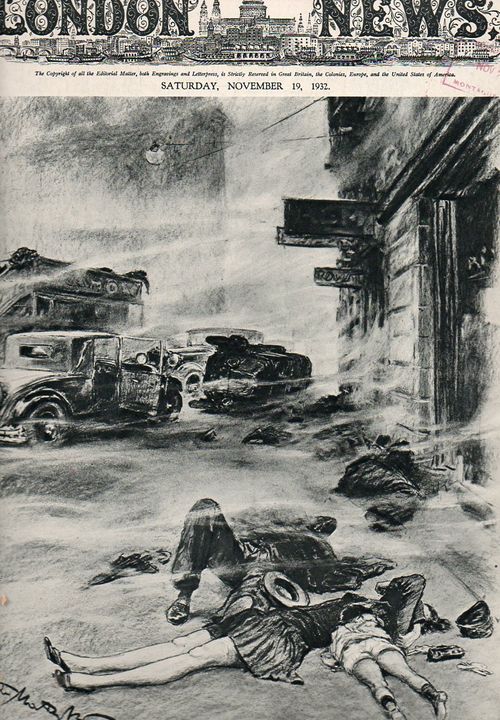

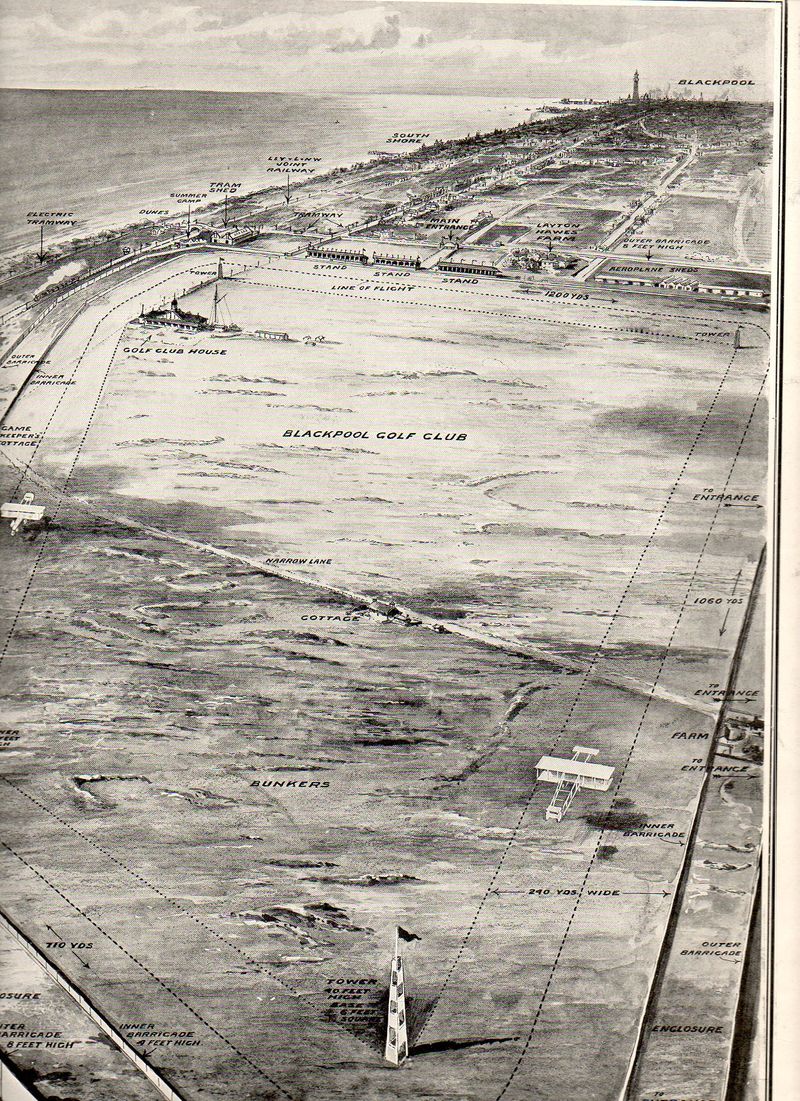

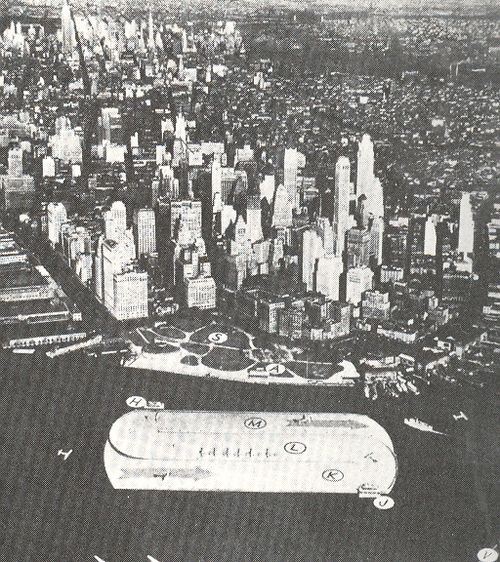

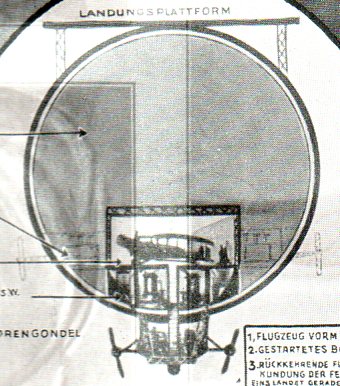

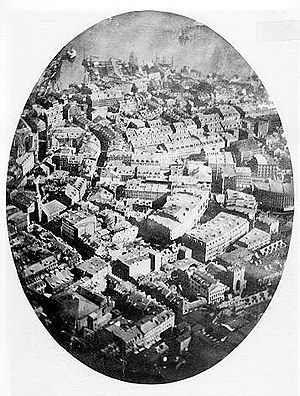

And this interesting image of a mock (or "mimic" as it was called in the report) attack on Milan in August, 1931:

There were a number of interwar aerial bombings that took place that kept the issue of mass destruction alive and well. For example, Britain used its air arm very convincingly in Iraq, bombing many places including Bagdhad in 1923; the Spanish bombed civilians into submission in Morocco, near Tetuan, in 1925, and the French crippled and destroyed their opponents--both military and civilian, it made no difference--in Damascus, Syria, also in 1925.

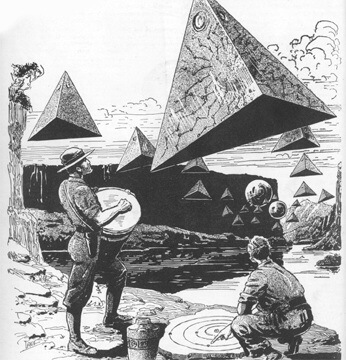

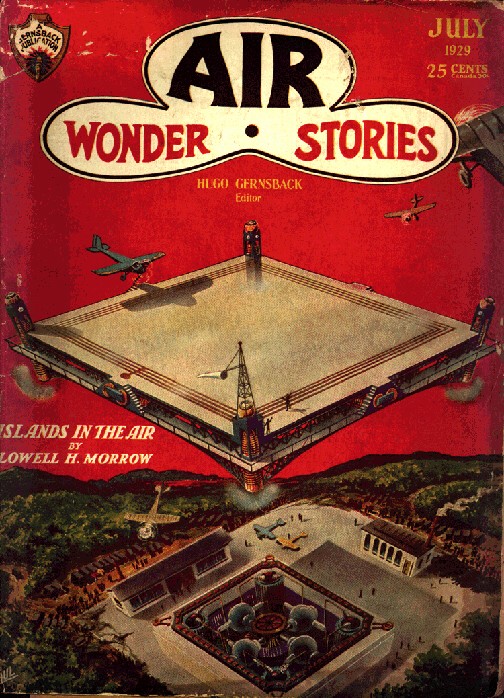

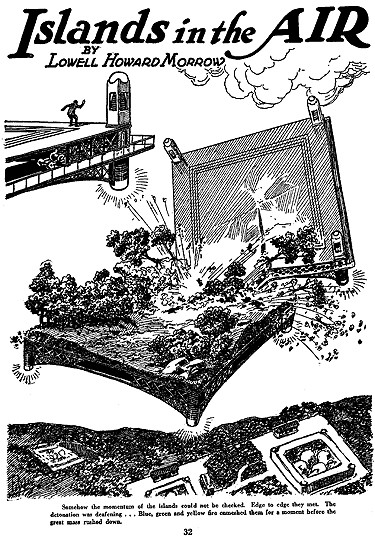

Fiction also harnessed the possibilities of air war, not the least of which included Armageddon-like scenarios for the semi-End of Days through the use of poison gas and “atomic” weapons. For example, deadly gas used in Anderson Graham’s The Collapse of Homo Sapiens (1923) and Neil Bell’s Valiant Clay (where the poison gas kills 1.5 billion) and Dalton’s Black Death (1934), while Reginald Glossop’s The Orphan of Space (1926) created an alien atomic spaceship which delivered holocaustal death to Soviets and Chinese and Communists in general. There were many more stories like this, not the least of which were the non-fiction strategy works, like Giulio Douhet, author of Dominion of the Skies (1921), legitimizer of the “strategic” bombing of civilian populations (in spite of the Hague Conference of 1907*), and JFC Fuller’s The Reformation of War (1923) which emphsized the new importance of air war and power and which also allocated the use of gas, justifying that morality because it could cause less harm than a conventional attack.

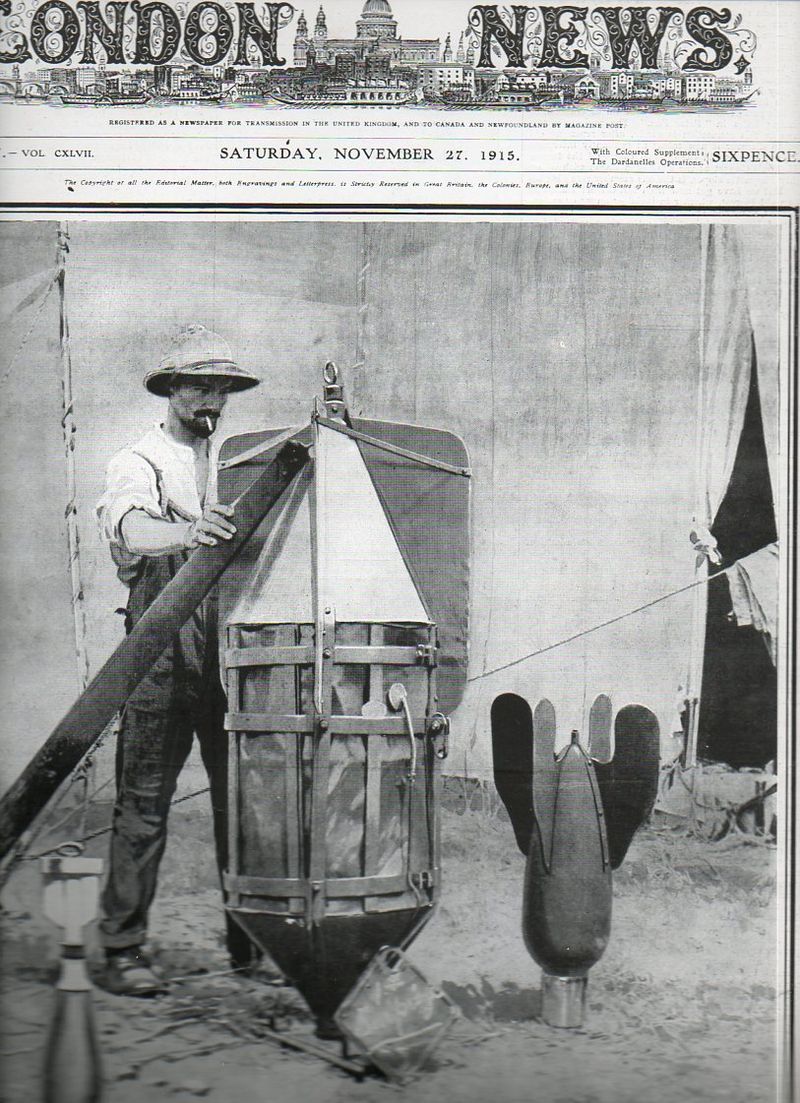

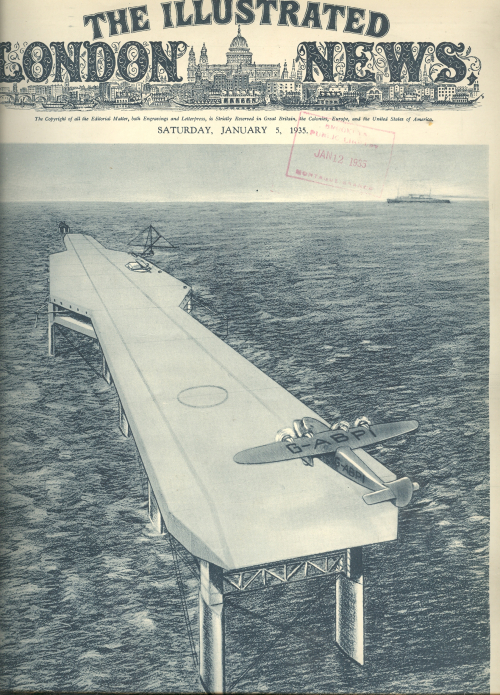

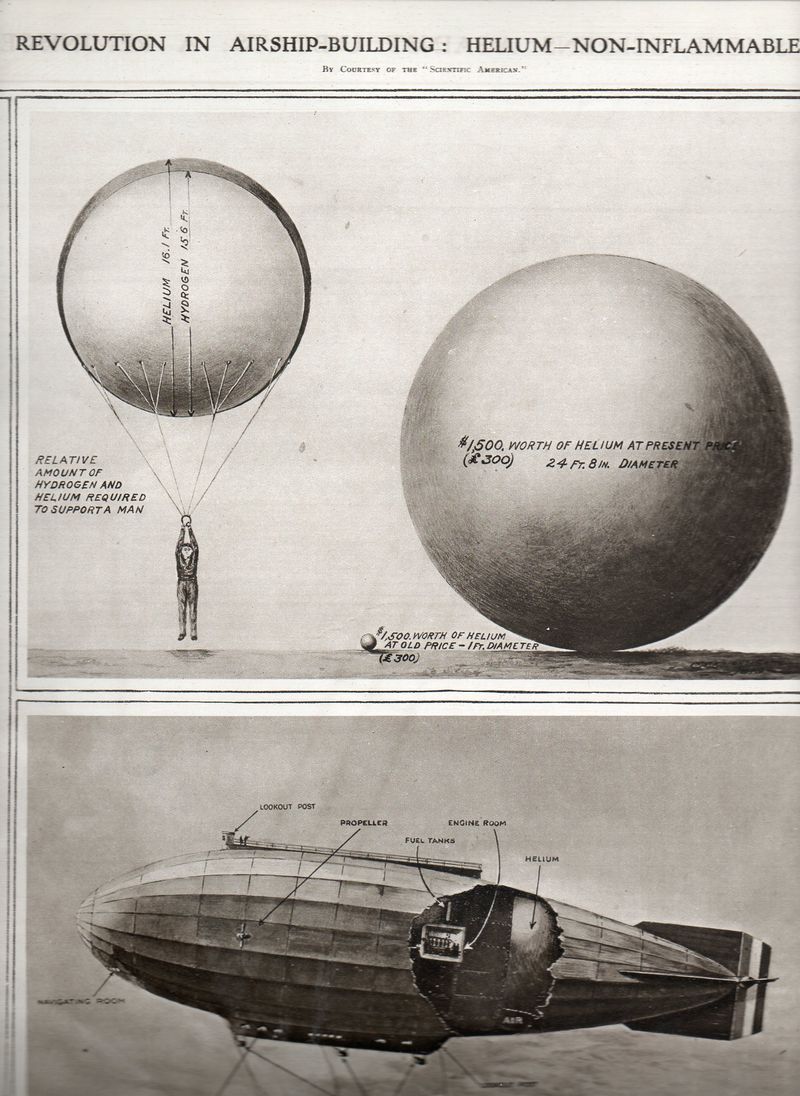

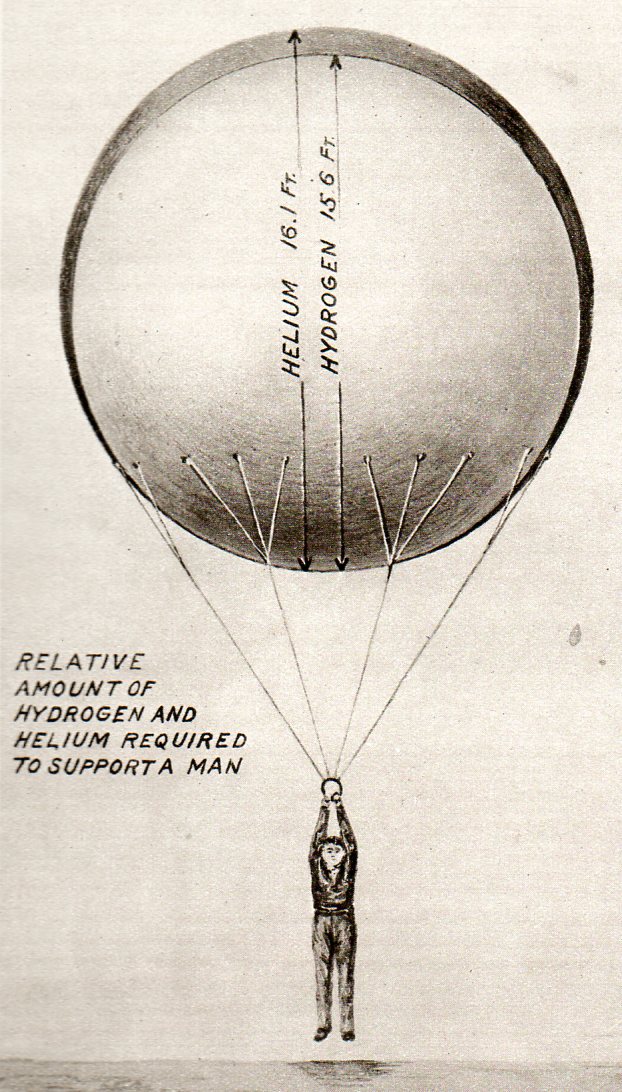

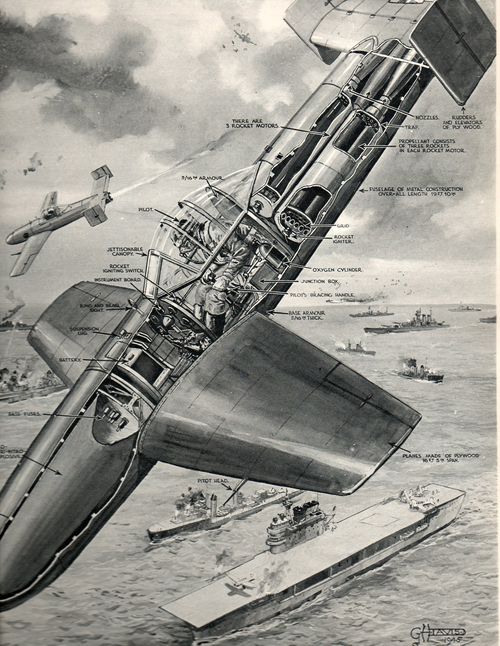

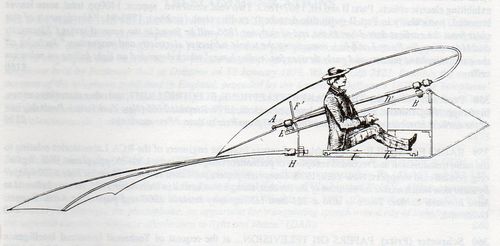

[Image below from :Mr Baldwin on Aerial Warfare", The Illustrated London News for 19 November 1932, illustrating the sort of aerial bombs that could threaten the population of London.]

The fear was real, and the capacity to cause mass death (espcially from poison gas) was substantial, even if in a still-developing form. Eight years hence, though, it would almost all come true (except for the poison gas part, at least for WWII), and in ways that weren't quite imaginable in 1932--500 B-29s flying criss-cross over Tokyo would've seemed more fiction than science to the 1932-person, even though that technology was only a dozen or so years away.

Notes

* This is where the bombing of civilian areas was specifically outlawed; what wasn’t defined, however, was what “civilian” meant–turns out that it was pretty loosely defined in the 20's and '30's.