JF Ptak Science Books Post 1354

Its easy to forget about the pre-Los Alamos Oppenheimer, especially for those who aren't necessarily interested in the history of 20th century physics. I was preparing to write something about a very brief window that seemed to have been opened in the 72 hours or so after the second atomic bomb was dropped....or perhaps from the time of he Hiroshima bomb. In any event, it was a short period, measurable in terms of dozens of hours, where people--even Robert Oppenheimer--had a sense of a sea-change regarding the bomb and peace, and that perhaps the thing was so terrible and so controllable that it might bring about the end of war. But the gloom of the reality of the future of the weapon--and the future weapon systems--settled in, and that illusory window was closed, if indeed it was ever actually open, which it really wasn't.

Not long after this, Oppenheimer was shuttled into the Oval Office to meet for the first time with President Truman--it must've been a worlds-in-collision moment, though it seems Oppenheimer was no quite himself, not quite as filled up as he should've been. Depressed, I'm sure, after having just gone through a bit of rough business as to who would be controlling the future of the bomb. Anyway, he met with Truman on 25 October 1945, in there with Truman for a 10:30 appointment, and things did not go well. Truman "asked" (apparently rhetorically) Oppenheimer his opinion on when the Soviets would develop the bomb. Oppenheimer simply said that he didn't know. Truman shot back "never", that the Soviets would never develop the bomb. I have no idea if Truman believed this or just was pissed with what he thought of his meeting with a "cry baby" Oppenheimer. Truman evidently told a number of different versions of this story, but one thing was for certain: he did say that he "never wanted to see that son of a bitch again".

If Oppenheimer wasn't depressed when he went into the Oval Office at 10:30, he was when he was promptly shuttled out for Truman's 11:00 meeting, which was with the postmaster of Joplin Missouri, Mr. Leslie Travis. My feeling (completely unsubstantiated) was that equal weight was given by Truman to both the 10:30 and the 11:00.But the man was a definite force in the relatively short time he spent in the high community, from the late 1920's to about 1942.

But just four years before, and the decade or so preceding it, Oppenheimer was a brilliant new force in the American physics community, a remarkable, brilliant talent with a big insight. And this is what brought m back to Oppenheimer on the first day of WWII.

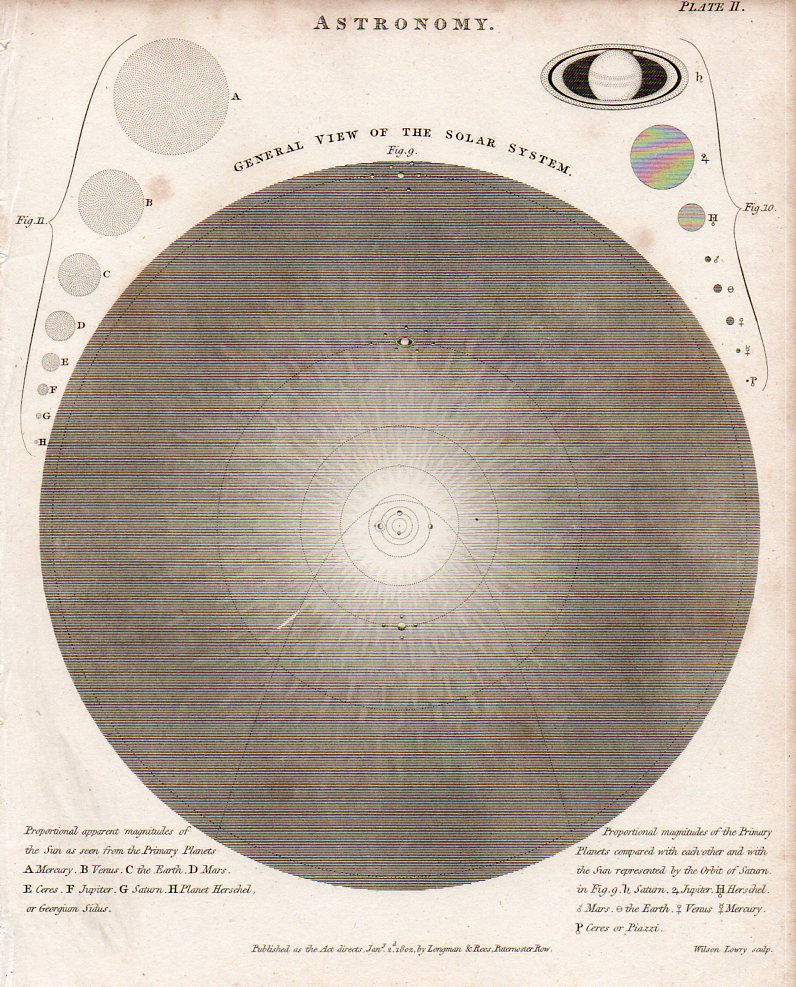

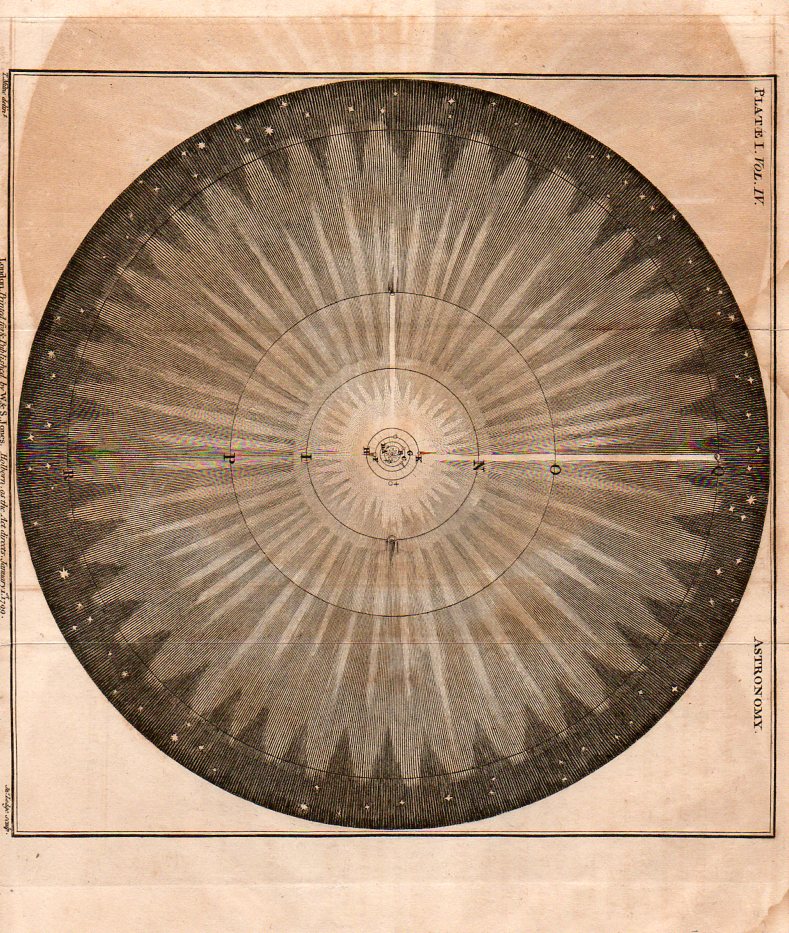

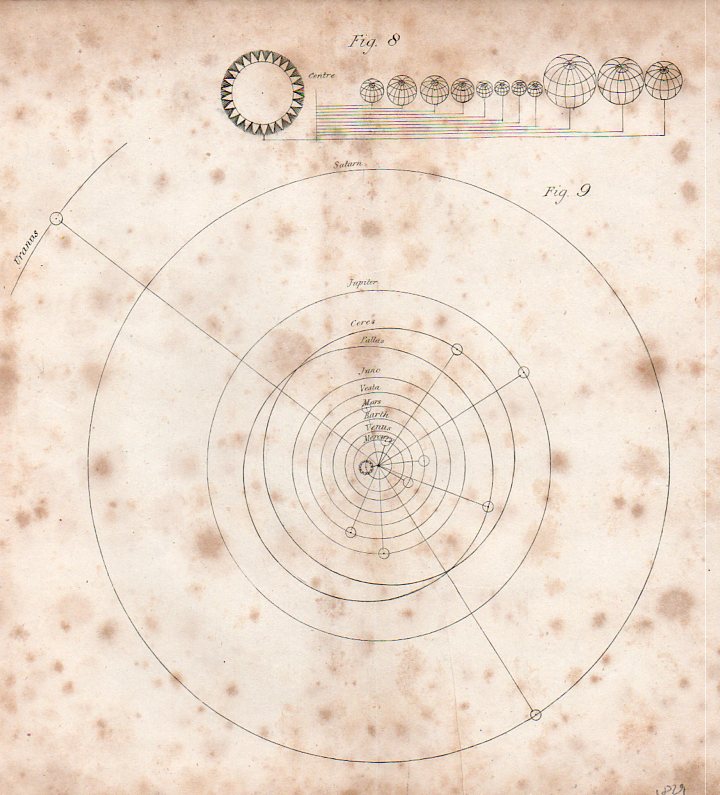

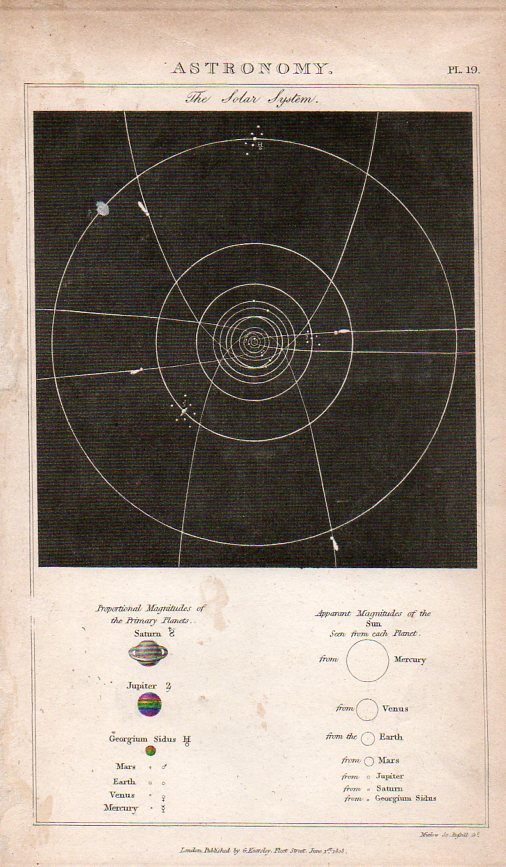

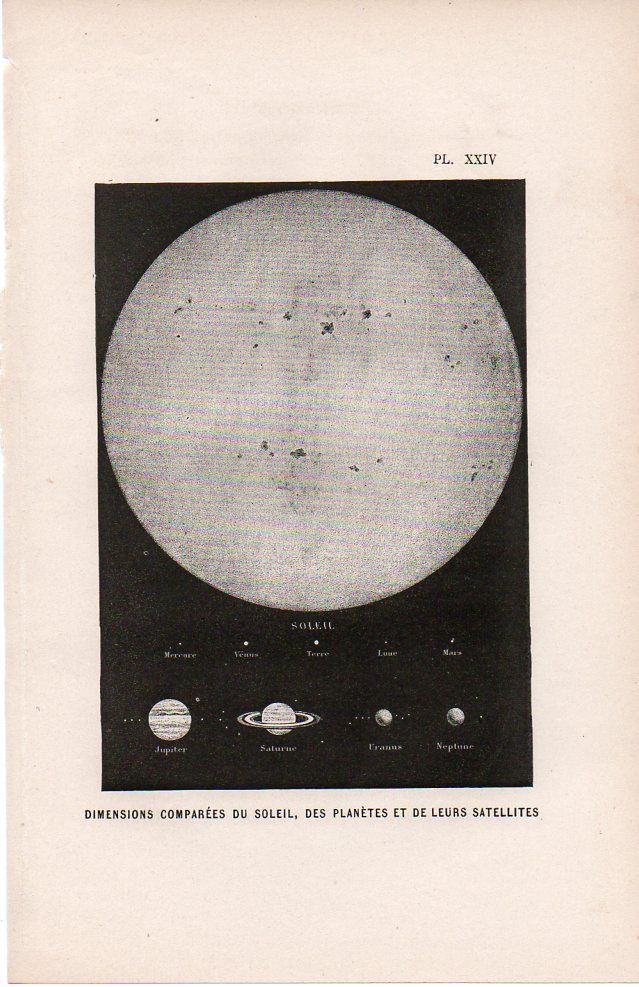

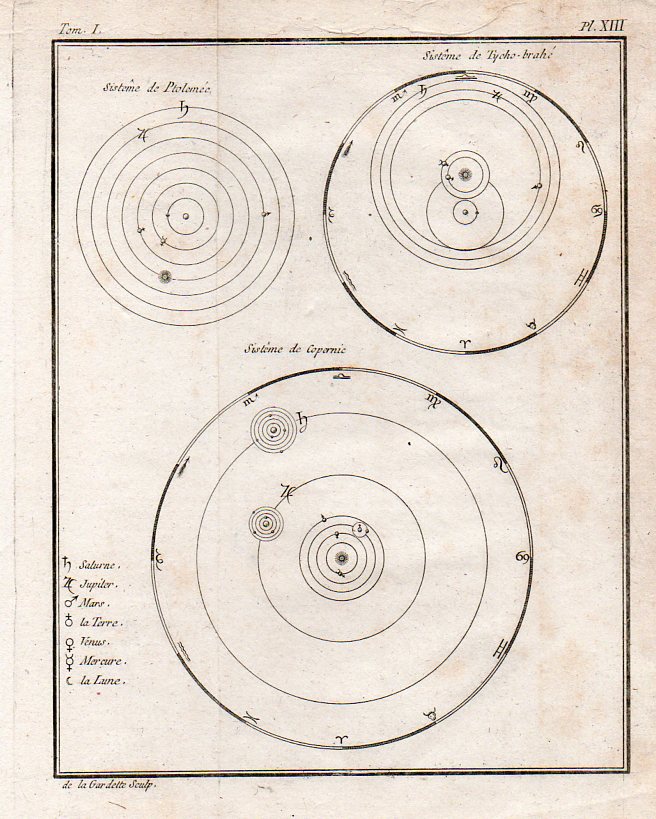

People tend to think of black holes as a Stephen Hawking-era phenomenon while the facts of the matter are that they began perhaps hundreds of year earlier, probably with Cambridge John Michell (1724-1793), back in the year of the end of the American Revolution, 1783 (and perhaps before). His famous experiment (known as the "Cavendish Experiment") was really only rediscovered in the 1970's in Michell's correspondence with Henry Cavendish. In those pages he hypothesized that there may evolve a star so massive (which he referred to as a "dark star' in Newtonian theory) that light itself might not be able to escape fro it, that the escape velocity for the light could never be reached, and that its phenomenal gravity would make the star impossibly dense. This was very similar to the dark star hypothesis of Simon Pierre de Laplace in his epic Exposition du Systeme du Monde which was published in 1796. Karl Schwarzchild's 1916 paper using Einstein's relativity paper of the same year discussed the possibilities of singularity (the Schwazchild limit of the diameter of black holes), as did (the beautiful) Subrahmany Chandrasekhar (one of the last men able to know everything) in 1928.

In hunting for a number of Richard Feynman papers here at the warehouse I happened to find this extraordinary effort by J. Robert Oppenheimer and G.M. Volkhoff in the 15 February 1939 issue of America's greatest journal contribution to physics, The Physical Review. Here (along with a preceding paper by Richard C. Tolman, issued in the same issue just above Oppenheimer, which were the analytic analysis used by O+V to base their estimates of nuclear forces) was established the Tolman-Oppenheimer-Volkhoff limit, which stated that if the state of evolution of neutrons forming a degenerate Fermi gas of extremely dense masses in neutron stars was more massive than .07 solar masses that it would collapse into a black hole or exotic/quark star; if the mass was below that limit, the star would not collapse due to the degeneracy pressure of neutrons and the strong force. The black hole part was left really to a second paper of 1 September 1939 (the day that the Nazis attacked Poland and the fighting began in World War II in Europe) when Oppenheimer teamed up with Hartland Snyder to write "On Continued Gravitational Contraction", when the two wrote about the singularity of the event. the paper met with little appreciation at the time, though the two papers today have lead to some of the most progressive ideas in 21st century astrophysics. (This paper is available at our blog bookstore, here.)