JF Ptak Science Books Post 1171

Porosity is a measure of spaces-in-between, voids in a material’s total volume. Some things certainly have visible porous elements, like a cotton shirt or netting, and others–like rocks and soil–don’t. Other elements are measurable but less visible and experimental than fluid flow though still experiential, like truth and falsity, or the concepts of good and evil, good taste and bad, love, generosity, felicity. Ideas like “god” are very porous, as are the prospects of salvation and redemption, and (getting into) heaven and hell.

Skin is also porous because it is composed of, well, pores. We don’t think of things like skin being permeable, as it holds in the vast amounts of liquids that make up the majority of the human body (for example). Football has porous defenses, a necessary design to the process of the game, because years of 0-0 games just won’t work so well as paid entertainment. Poromechanics in real and abstract bits is all a matter of degree. And direction.

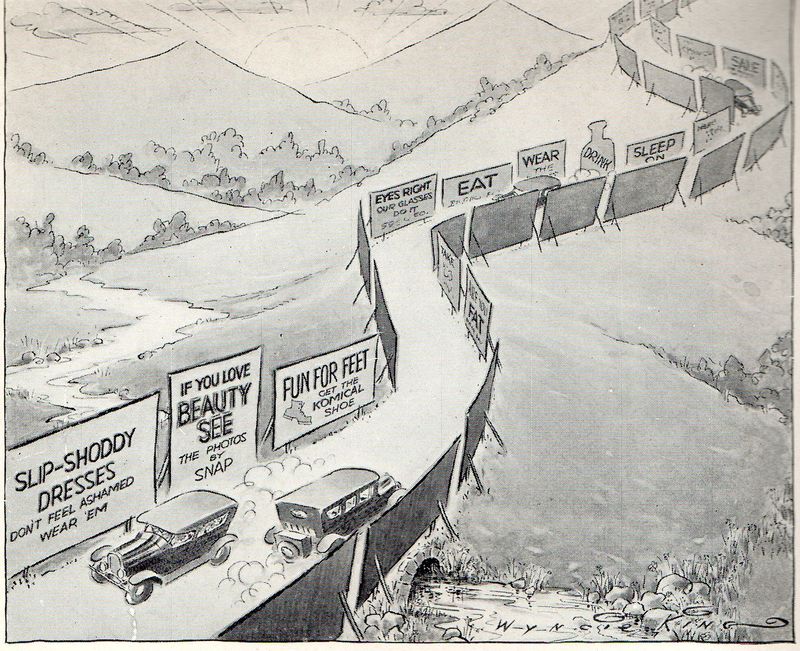

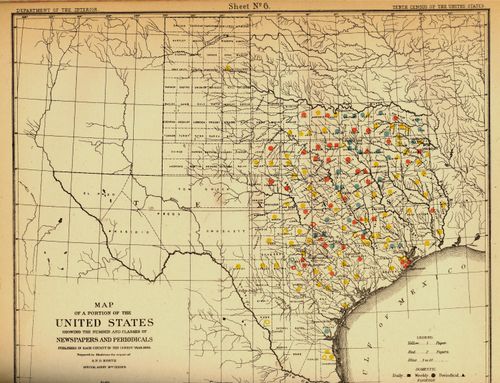

The American border is fairly well porous–much less now than it used to be of course. There’s 3,987 miles of border (excluding Alaska) with Canada, and another 1969 miles between the U.S. and Mexico (1241 of those shared with Texas), so there’s a lot of room for room–for people trying to get into the country. The flow of people through/over the borders weren’t always gong one-way–the expansion of the country is a history of the mythic pioneer/settler moving into space contiguous to property that was owned by the U.S. (Actually, it wasn’t all contiguous, adventurers and “explorers and entrepreneurs and filibusterers reaching far and wide.) It would be interesting to know how many miles of variable borders within the U.S. we have slipped through over the last few centuries--my offhand guess is that it is an order of magnitude greater than what we have right now.

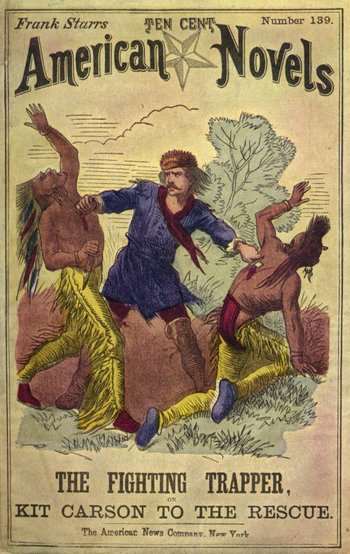

Before we constructed massive walls and armed our borders, before we started to erase the incised sentiments on the base of the Statue of Liberty, the border wars of the United States were being fought going the other way ‘round. The borders of the country were extended in many different ways, not the least of which were what we would call “pioneers”–plus of course politicians and the military, all deeply at work in establishiung the sactions of expansion.

For example, in the 1800-1850 period, there were 21 major attempts to access foreign properties to become part of the United States. Ten of these were attempts made to purchase the land outright–only Louisiana (and that is a gigantic “only” was wholly successful, with Sonoma being half-successful. Five of the other cases-- East Florida, West Florida, Texas, New Mexico and Alta California--came to us via wartime acquisition. Attempts to buy and bully Mexico for Baja didn’t work; Yucatan and Cuba escape our proposals for annexation and purchase as well, while Chihuahua resisted purchase, invasion and annexation.

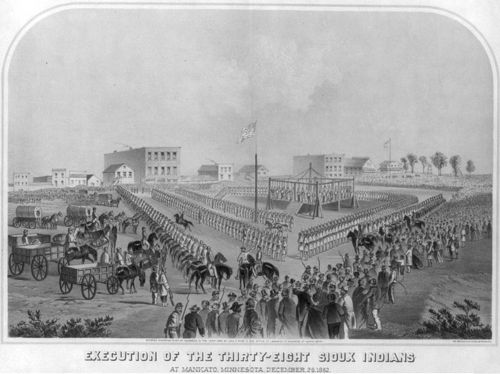

All of this excludes Indian lands, of course, a list of the tribes involved in the 709 seizures1 can be found in the continued reading section, below. (That’s the number of “transactions” for the 110 year history between 1784 and 1894, which extends beyond the 1800-1850 slice of our expansionist pie; there were still a hundred or so motions against the Indians during this time, not to mention the dreadful Southern Removals of the Five Civilized Tribes as well as the disastrous removals in Indiana.)

Conquest and purchase has been the name of the game in moving the Americans through our borders, an exercise of great regularity and incredibly high return. Again putting aside the Indian question, had we not pushed up against the owners of these lands in the first place and absorbed them in the second, instead of having California, Utah and Texas we may well have had the Republics of California and Texas and the entity of Dereret, not to mention a wide swath of the southwest (including New Mexico, Nevada and part of Colorado) reaching up nearly to SLC that still belong to Mexico.

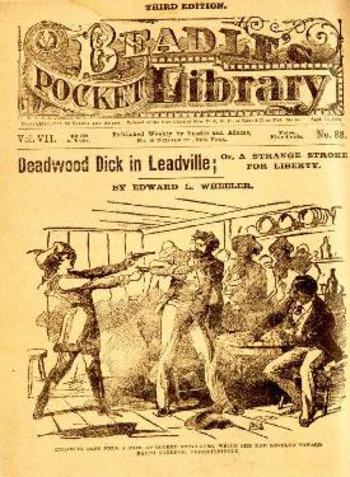

And what it all boils down to after the borders have been passed through and moved forward, again, are the people that wind up staying–pioneers, farmers. The log cabin came to symbolize this spirit in the 19th century, a picture of progressive civilization and stability, of spirit, of achieving Manifest Destiny. In my own collection of images of log cabins (prior to the Civil War), there are very few of these structures that show people in or near them. More often than not, the pictures are silent; every now and then, there is a woman in the doorway or inside looking through a window–a symbol of innocense and felicity. There are images with the log cabin in the background, the foreground filled with pulled stumps and men plowing the fields (with and without horses) I don’t own a single image that shows a man with a gun. (I’ve not done a survey on this issue, but that’s my overall impression over the years.) A subtle message I think was definitely being sent.

Even the name “America” proved to be exceptionally porous. At one point it stood to include North and South America, and then it changed to exclude South and Central, and then Canada, and then Mexico–it really only related to the United States during the period of greatest nation building.

This is just an interesting thing to think about now when we discuss closing our borders–those lines had to get to those positions somehow over the last 500-odd years.

Notes:

1. Indian Land Cessions in the United States,1784-1894, United States Serial Set, Number 4015; this is the second part of the two-part Eighteenth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1896-1897. “The Schedule of Indian Land Cessions subtitle notes that it indicates the number and location of each cession by or reservation for the Indian tribes from the organization of the Federal Government to and including 1894, together with descriptions of the tracts so ceded or reserved, the date of the treaty, law or executive order governing the same, the name of the tribe or tribes affected thereby, and historical data and references bearing thereon."

Sometimes just seeing hte extent of a list of names gives you a much greater appreciation for the numbers involvewd than the sheer number itself:

Acoma Pueblo

Alabama

Alsea et al

Apache

Apache (Eastern bands)

Apache (Jicarilla bands).

Apache (southern).

Apache (Southern).

Apache (Western bands)

Continue reading "A Note on American Two-Way Border Wars " »