JF Ptak Science Books LLC Post 631

[A continuation of the blog series "A History of Blank, Empty and Missing Things"]

The

sweetest pleasures come from unexpected sources. Mozart--who loved the game of billiards

and was an exceptional aficionado1 of the game while playing it with little

skill-- enjoyed composing on the table as well, rolling balls in geometric patterns across it

while working. To observers it might have seemed as though he was interested in

the patterns themselves; it delightfully turns out that what he was really looking at were

the changing reflections in the surface of the balls.

Years

ago my wife (Patti Digh) and I visited an artist in his studio at the lovely

high-road-to-Taos town of Truchas, New Mexico. We watched the artist at work for quite some

time—well, actually, we listened to him work.

Although he was a lovely painter, the visual impact was overwhelmed by the sounds that he made padding back

and forth (he was working on a big canvas) across an old and musical wooden

floor --it deeply interesting, and the sound stays with us to this day.

I

enjoy these quasi-synesthesic experiences a great deal, though they are very

hard to “find”. Sometime though they slip into the print world, and I include three

examples below.

(1)

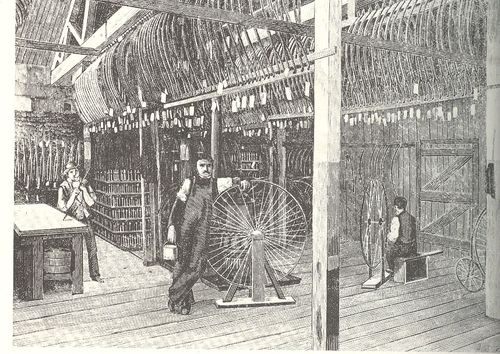

Putting the Pulp in Fiction, and Fact: the Sharp First Step in Paper-Making

Just

about the first step in making paper is collecting and preparing the raw

materials from which the paper is made.

Linens, cottons, wood and straw (among other things) would be reduced to

a pasty pulp through vigorous pounding, tearing, wetting stabbing and rending,

all of which would be reduced to a pasty, fibrous pulp which would wind up after

a bit spread over a wire mesh until dried and then, through a great

non-miracle, becoming paper. This is a

process that was little changed in the Western world for many centuries.

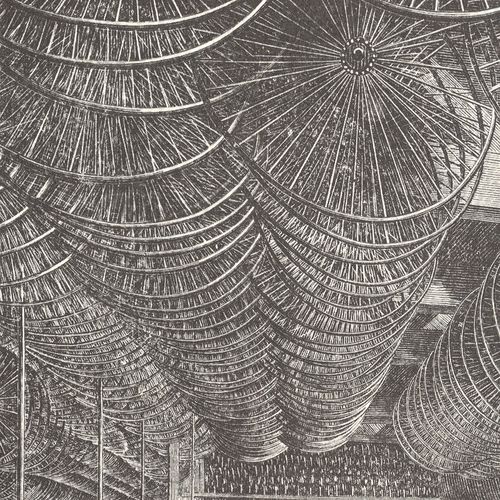

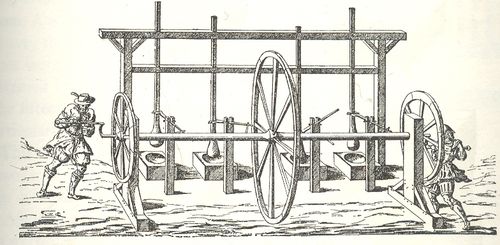

The

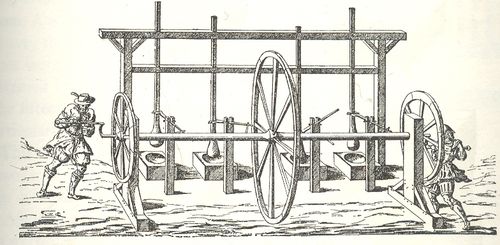

most lovely of these early pulp-rendering, “stamping” machines, to me is the

fabulous two-person human-powered stamper/shredder, published in 1579. (I don’t

know the original source for the wood engraving; this image appears in Charles

Singer’s monumental History of

Technology, from the Renaissance to the Industrial Revolution, vol III.

The

men turn crank, crank turns wheels and rod, rod turns arms, arms forced to move

vertical poles up and down, stampers on the end of poles pound the rags. Actually the stampers had changeable stamps

so that the man-machine could start with a spiked stamper for rendering and

then move to a roundish stamp for pounding into decomposition in a wooden bowl

with mushy water.

I

just really like the machine and its representation, and of course the round

stampers and bowls of mush. It all seems

so innocent in a creaking antiquarian way—but the great surprise for me is that

I can just about hear this machine at work.

The all-wooden structure with slowing-turning wheels grinding against

its constituent parts, worn smooth from use; the slow pounding of the stampers

into the thick paste; the creaking motions of the too-slender

superstructure. I can hear it about as

clearly as I can hear the soft/high clinking of the bottles in the milkman’s

tray.

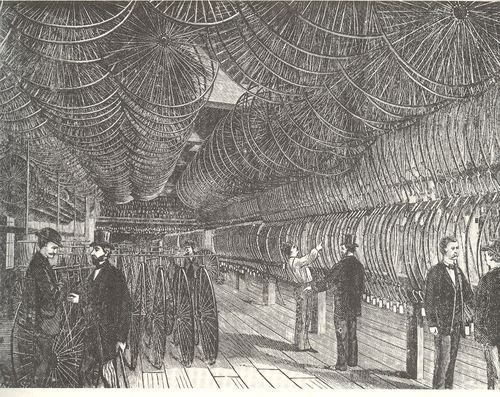

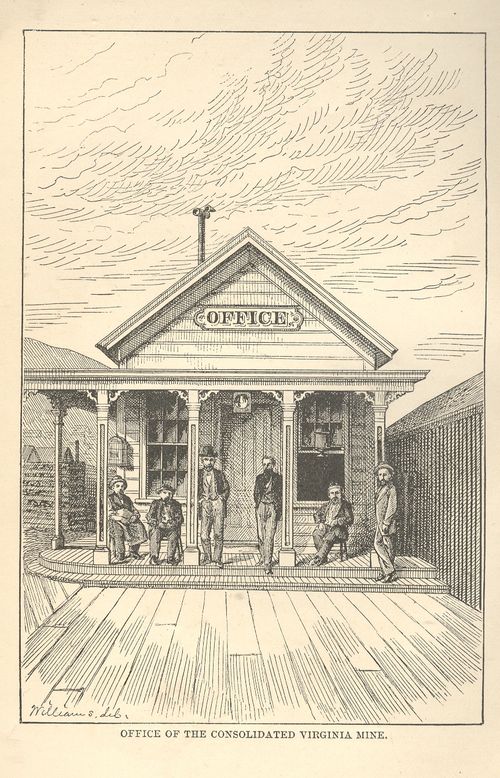

(2) A Scene of Western Quiet

The image comes from William Wright's The History of the Big Bonanza and was published in 1877. It is a very

simple scene (“Office of the Consolidated Virginia Mine”), nicely and

proportionally arranged, though somewhat challenged by its understanding of linear

perspective. For reasons I don’t quite understand it might as well have been a

picture of the high desert with no settlement whatsoever. It simply seems still, and very quiet.

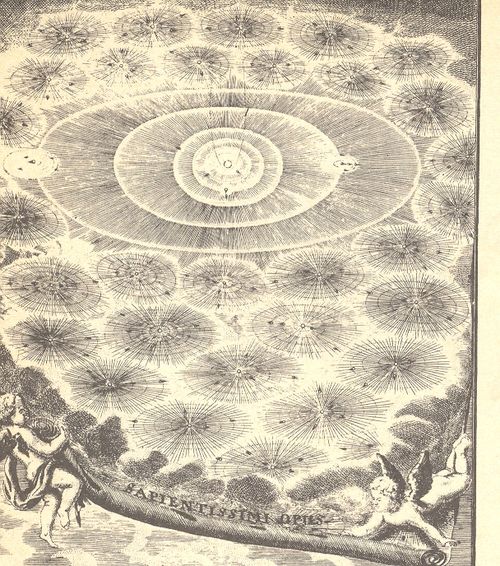

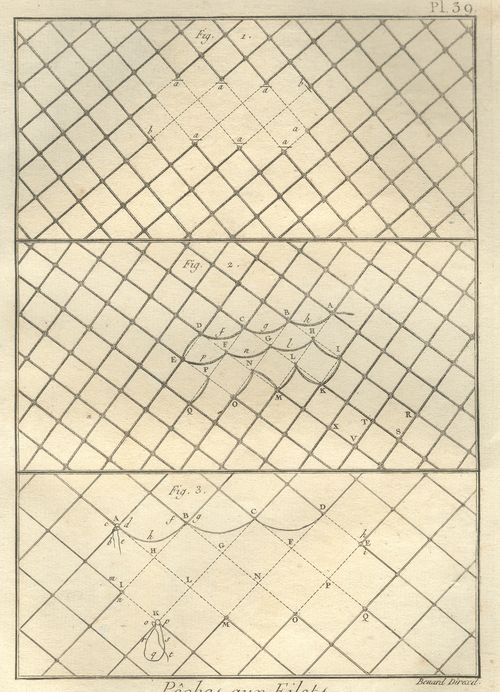

(3)

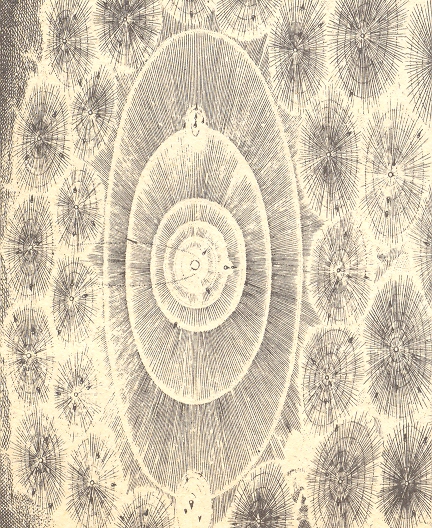

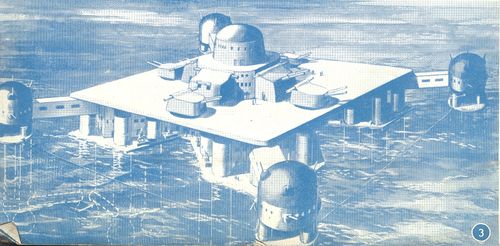

Electrical Hum (and Ozone) Fishing Nets

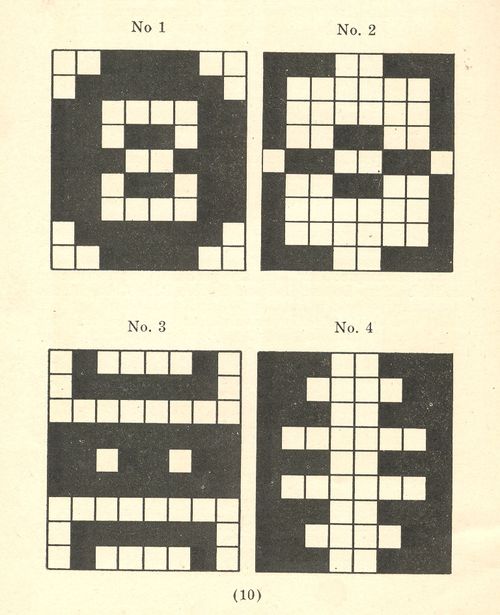

This

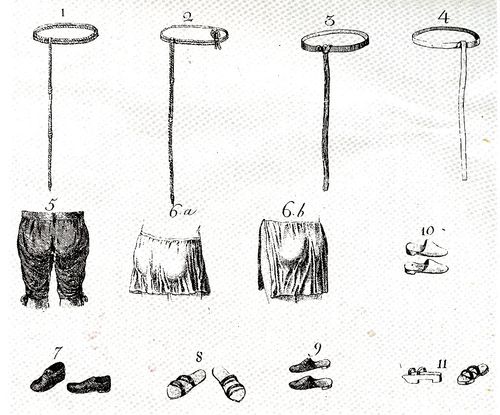

image, from the quarto edition of the great Diderot and d'Alembert Encyclopedie (published over a number of years in the late 18th century), shows (I think) the

ways to mend broken fishing nets. I have a definite sense of a high electrical

hum from this, along with the added whiff of ozone. Its hardly something that was intended by the

artist, but it was the first thing that registered with me when I bought this

print 25 years ago.

Things

like this are available to us all of the time, simply waiting to be heard while

being seen.

Notes

1. After his death Mozart's estate was reckoned, and the contents of his house and belongings were catalogued. It was recorded that he had a very nice billiard table, and that he also had 12 cues. Now 12 cues might've been there because he liked the feel of the wood, or that he liked their artistic merit on the wall or in the corner. That, or he had a lot of people coming over to play. I like the later interpretation. Also, I cannot remember the reference for the ball/reflection story; please don't tell me that it is wrong.