I posted something yesterday on this, but made a video of the whole thing (plus extras) this morning, with some decent music.

I posted something yesterday on this, but made a video of the whole thing (plus extras) this morning, with some decent music.

Posted by John F. Ptak in Absurdist, Unintentional, Bad Ideas, Women, History of | Permalink | Comments (0) | TrackBack (0)

JF Ptak Science Books Post 1254

There was a certain something going on in the 1950's with nova-express B-film ladys-in-trouble/bad girl/smashnose kissing movies that were made for $5,600 in three days with two days of quality control. The posters made for these beauties were a thing unto themselves, a self-contained and self-limiting genre, a found case of bizarro design and muted inelegancies.

There was a certain something going on in the 1950's with nova-express B-film ladys-in-trouble/bad girl/smashnose kissing movies that were made for $5,600 in three days with two days of quality control. The posters made for these beauties were a thing unto themselves, a self-contained and self-limiting genre, a found case of bizarro design and muted inelegancies.

The posters look like their movie names: Juvenile Jungle, Betrayed Women, Girls in Prison, One Girl's Confession, Dragstrip Girl, Girls on the Loose, Pick Up, Girls in the Night, Live Fast Die Young, Alimony Running Wild, Hot Rod Rumble, Running Wild, Blonde Bait, Captive Women, The Party Crashers and of course Lost, Lonely and Vicious.

Generally I think that folks see the big design and the colors, but lurking behind all of that are usually image-bits that sorta tell a part of the story of the film, but in a stubby, grubby way. So I decided to do a little archaeological dig into some of these and give those small images some life through magnification. Sometimes they're surprising and look good big; sometimes they're just badly design and goofy, and would look better smaller, very much smaller---dot-small. Here's a few examples (I'll show the detail first and then the larger, full image of the poster after):

Detail

Full poster:

Full poster:

Detail

Full poster:

Detail:

Detail:

Full poster:

Detail

Full poster, 1955.

Detail:

detail:

Detail:

detail:

Full poster, Betrayed Women, 1955:

Detail:

|Full poster, Juvenile Jungle, 1958

|Full poster, Juvenile Jungle, 1958

detail:

Full poster, Captive Women, 1952

Full poster,Captive Women, 1952

Detail:

Full poster, Lost, Lonely and Vicious, 1952:

Detail:

Detail, Party Crashers, 1958

Posted by John F. Ptak in Absurdist, Unintentional, Bad Ideas, Women, History of | Permalink | Comments (0) | TrackBack (0)

JF Ptak Science Books Post 1252 (Rapid Post)

Part of the series Blank, Empty and Missing Things

Fred Catlett's Rehabilitation of Sub-Standard Housing Areas (1942) isn't so much about "rehabilitation" of the houses themselves but to their neighborhoods and surrounding areas--the "inadequate" housing would be demolished, disappeared, replaced, to re-insure the valid tax basis of the larger area/neighborhood. Nothing is said about where the original people would go while their old neighborhoods were being razed or whether or not they would return to the new housing.

The vocabulary here isn't so surprising in and of itself, but rather with teh overwhelming completeness of it. I'd suspect that at some point Mr. Catlett ("Member Federal Home Loan Bank Board") would throw some sort of bone to the interests of the occupants of those substandard houses, some interest or emphasis to the people involved. And even though the pamphlet is only 12 pages long, maybe 5000 words, it was certainly long enough to share some concern or kindness to the occupants of those houses.

"Better housing projects break up slums but not until fine homes have decayed and been ruined and many thousands of dolalrs in loses have been suffered"writes the author. I understand that the man was protecting the material bases of his institution, but ot have the entire document be absent of any consideration to the people being houses I find remarkable. (The original pamphlet is available from our blog bookstore.)

"Better housing projects break up slums but not until fine homes have decayed and been ruined and many thousands of dolalrs in loses have been suffered"writes the author. I understand that the man was protecting the material bases of his institution, but ot have the entire document be absent of any consideration to the people being houses I find remarkable. (The original pamphlet is available from our blog bookstore.)

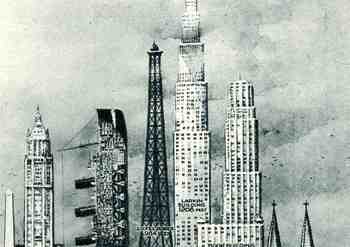

This wonderful display (appearing in The Illustrated London News for 26 March 1927, page 518) of quantitative data isn't quite as whimsical as it appears in detail, though I can think of only a few (antiquarian) times that I have seen a ship made part of a cosmopolitan vertical cityscape. It is a great way of comparing two disparate, out-of-place equals, and certainly can get the idea of the size of something as stand-alone and solitary as a great ship to children (and adults, too) by comparing it to something as obvious as a tall building., This time its really just comparing the length of the SS Mauretania with the heights of some famous and notable buildings. (The Mauretania, 1906-1935, was a fabled, luxurious and fast ocean liner of the Cunard line; it was refitted for a resurgent oceanic service at about this time.) In the larger, expanded second image we see the Mauretania stacked up against (from left to right) the Washington Monument (555'), the Woolworth Building (792'), the Mauretania (790'), the Eiffel Tower (984'), the Larkin Building (proposed at 1208'), the Book Building (873'), the Koln Cathedral (512') and the Statue of Liberty (305'). The Larkin Building (not the F.L. Wright structure of the same name) was a proposed super-tall of 110 floors for 330 W. 42nd Street that was proposed in 1926 and not canceled until 1930, and which would've been the tallest building in the world. (For an interesting site on the cancellation of tall buildings, see HERE.) In any event, this was a big ship--the largest in the world when it was launched as a matter of fact--and the drawing is wonderful. Upon closer inspection, there is a terrific amount of detail in the cross section of the ship.) (This original print is available at our blog bookstore.)

a few (antiquarian) times that I have seen a ship made part of a cosmopolitan vertical cityscape. It is a great way of comparing two disparate, out-of-place equals, and certainly can get the idea of the size of something as stand-alone and solitary as a great ship to children (and adults, too) by comparing it to something as obvious as a tall building., This time its really just comparing the length of the SS Mauretania with the heights of some famous and notable buildings. (The Mauretania, 1906-1935, was a fabled, luxurious and fast ocean liner of the Cunard line; it was refitted for a resurgent oceanic service at about this time.) In the larger, expanded second image we see the Mauretania stacked up against (from left to right) the Washington Monument (555'), the Woolworth Building (792'), the Mauretania (790'), the Eiffel Tower (984'), the Larkin Building (proposed at 1208'), the Book Building (873'), the Koln Cathedral (512') and the Statue of Liberty (305'). The Larkin Building (not the F.L. Wright structure of the same name) was a proposed super-tall of 110 floors for 330 W. 42nd Street that was proposed in 1926 and not canceled until 1930, and which would've been the tallest building in the world. (For an interesting site on the cancellation of tall buildings, see HERE.) In any event, this was a big ship--the largest in the world when it was launched as a matter of fact--and the drawing is wonderful. Upon closer inspection, there is a terrific amount of detail in the cross section of the ship.) (This original print is available at our blog bookstore.)

JF Ptak Science Books Post 1250

"There were giants in the earth in those days; and also after that, when the sons of God came in unto the daughters of men, and they bare children to them, the same became mighty men which were of old, men of renown." Genesis 6:4-5 (KJV).

Our dog Blue is a giant Jack Russell Terrier--mix. He's a Jack St. Bernard/Jack Russell--a St. Jack--and at 50+ pounds is either a Giant Jack or a mini St. Bernard. He behaves like the St. Bernard. One wonders about the mechanics of the thing--similar to Mr. Gulliver in Jonathan Swift's A Voyage to Brodbingnag (1727), in which the hero (or anti-hero) though he is disgusted by the gigantic women of the place nevertheless seeks and accomplishes some sort of romantic union with the handmaidens of the giant queen. And this all puts me in the mind of giants--actually, I'd like to put together an Alphabet of Giants, with this being the beginning. And to start at the beginning is Athanasius Kircher--the incredible Kircher, who produced thousands of pages of excellent analysis and cutting-edge technical/physical thinking as well as hundreds of pages of highly imaginative scientificiana--and his generic giant, featured in Mundus Subterraneus in 1646.

Giants have certainly been around for a long time, though imaging that imagination is less ocmmmon early on in the history of the illustrated book.

There's no lack of giants in ancient mythologies and legends--the Hindu Daitya, Mohamed's depiction of a 100-foot-tall Adam, the Greek Antaeus (the children of Heaven and Earth, of Uranus and Gaea), the sleepy Encedladus, the Nephialim, and so on. One of the most glorious of the big people stories is the beautifully-named Gigantomachy, in which the gods of Olympus engage in an enormous confrontation with Chaos and Aleyoneus. The "good" (though not very) guys win.

There's actually about half-an-alphabet residing just within the Greek Titans (Atlas, Crius, Cronus, Coeus, Gaia, Hyperion, Iapetus, Mnemosyne, Oceanus, Phoebe, Prometheus, Rhea, Theia, Themis, Tethys), but I'd like to expand this if I can. A fuller, more diverse listing of giants and giant-groups follows: Anakim (Jewish mythology, references in the Old Testament), Argus Panoptes (Greek mythology), Bestla (Norse mythology), Cyclopes (Greek mythology), Daityas (Hindu mythology), Epimetheus (Greek mythology), Fachan (Celtic mythology), Gargantua and Pantagruel, Gigantes (Greek mythology), Gog and Magog (Jewish mythology), Goliath (Book of Samuel of the Bible), Hecatonchires (Greek mythology), Iovan Iorgovan (Romanian mythology), John Henry (American folklore), Jotuns (Norse mythology), Kaour (Celtic mythology), Menoetius (Greek mythology), Nimrod (Jewish mythology, OT), Oni (Japanese folklore), St Christopher (Roman Catholic saint),Talos (Greek mythology), Titans (Greek mythology--Atlas, Crius, Cronus, Coeus, Gaia, Hyperion, Iapetus, Mnemosyne, Oceanus, Phoebe, Prometheus, Rhea, Theia, Themis, Tethys), Zipacna (Mayan mythology).

For the most part I've stayed old with these images, except for the 50-Foot Woman, the Giants are generally not from the modern fantasy/sci fi gernre.

So, Part 1:

A. ALICE. John Tenniel's Alice in Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland.

A. Arthur. King Arthur's Giant.

B. Beanstalk Giant. Jack and the Beanstalk, John D. Batten

B. Bunyan, Paul. By Allen Lewis.

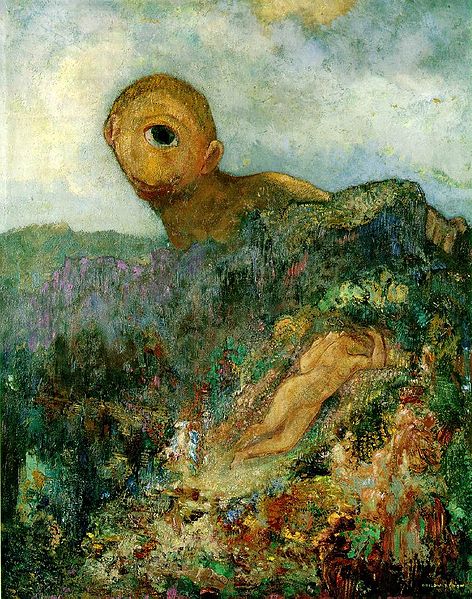

C. Cyclopes. By Ordilon Redon.

.

E. Ecclesia. "Ecclesia", or the depiction of Church as the Bride of Christ is a representation of a woman giant, and is seen in Scivias, by St. Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179).

F. Fatna. The giants Fafner and Fasolt seize Freyja in Arthur Rackham's illustration of Richard Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen

P. Pantegruel.

R. Rukh. "The Rukh which fed its young on elephants", by E.J. Detmold. For The Second Voyage of Sinbad the Sailor from The Arabian Nights, 1924.

W. Woman, 50-Foot.

Women don't often appear though as giants--at least until modern times.

Z. Zeus.

Zeus and three Gigantes, drawing based on the Zeus Pergamon Altar.

Posted by John F. Ptak in Absurdist, Unintentional, Mythology, Perception, Perspective | Permalink | Comments (1) | TrackBack (0)

JF Ptak Science Books Post 1243

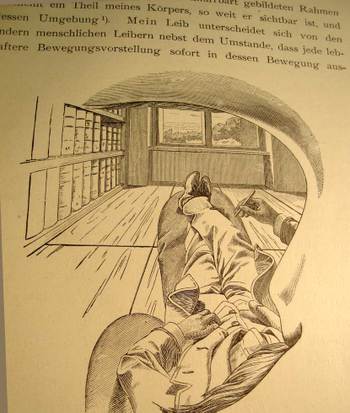

I cannot think of another illustration by a scientist or philosopher who attempts to explain their own--literal, interior,physical--view of the world and then offer what this looks like to the reader from inside his own head, looking out through his own eye. That's exactly what Ernst Mach is doing right here on page 15 of his influential book Die Analyse der Empfindungen, the fourth German edition ("The Analysis of Sensations and the Relation of the Physical to the Psychical") (Jena, 1903)

I cannot think of another illustration by a scientist or philosopher who attempts to explain their own--literal, interior,physical--view of the world and then offer what this looks like to the reader from inside his own head, looking out through his own eye. That's exactly what Ernst Mach is doing right here on page 15 of his influential book Die Analyse der Empfindungen, the fourth German edition ("The Analysis of Sensations and the Relation of the Physical to the Psychical") (Jena, 1903)

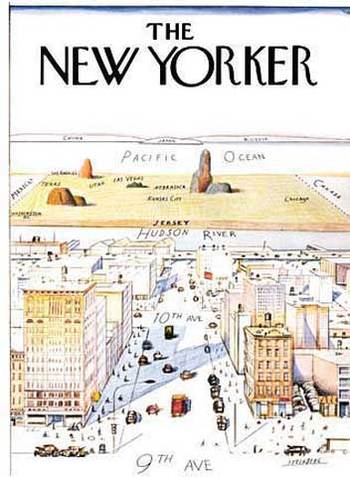

There is nothing in this world for Mach that is not admissible to the human brain that is not empirically verifiable--that is, the world is nothing but awash in sensation and that sensation itself forms part of the experience of, well, experience. I've actually never been interested in the philosophy of science, and this is one of the reasons why. Nevertheless I boldly break through my own prejudices to enjoy this phenomenally original image, drawn from the inside of Mach's working mind, looking out through his eye socket, over his mustache, under his eyebrow, around his nose, out across his body and then leaping into the rest of the world. I think he does make his point about the essential nature of the observer. And much like the classic Steinberg New Yorker cartoon of the world view of the New Yorker (of course this includes only Manhattan), I know some number of people who have transposed their bodies much like Herr Mach into the Steinberg map--except that their worldview ends basically at the Hudson River (Mach's feet) with the rest of the world being the sliver out there beyond the river (Mach's window) until you go 359 degrees around the world to get back to the East River (and back inside Mach's noggin). It is an unusual world view to have, but someone has to have it so that we can at least identify it so.

nature of the observer. And much like the classic Steinberg New Yorker cartoon of the world view of the New Yorker (of course this includes only Manhattan), I know some number of people who have transposed their bodies much like Herr Mach into the Steinberg map--except that their worldview ends basically at the Hudson River (Mach's feet) with the rest of the world being the sliver out there beyond the river (Mach's window) until you go 359 degrees around the world to get back to the East River (and back inside Mach's noggin). It is an unusual world view to have, but someone has to have it so that we can at least identify it so.

I just like the picture.

Continue reading "Looking Inside Out--Ernst Mach's pre-Escher Image" »

JF Ptak Science Books Poat 1236

{Part of this blog's History of Holes and History of the Future series.]

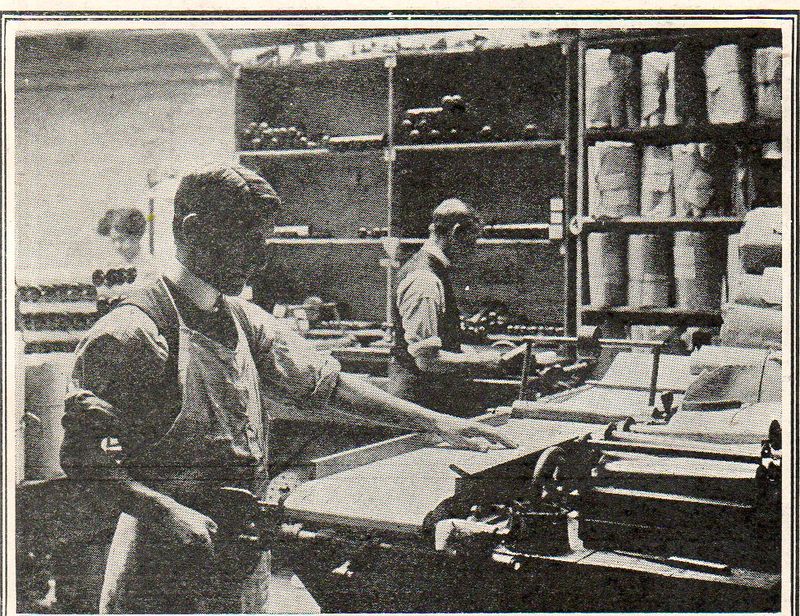

There is a certain layered, geological dystopic quality to the images of these men laboring at producing piano rolls for player pianos (and found in The Illustrated London News for 18 December 1909). This is true especially for the details, the small boxes in the background to where the rolls are being "processed"--music pounded out with metal points on a hard surface, as though produced by whatever it was that was in those little labeled wooden containers, far removed from the artistry of melody. These are images of a culture being made into hundreds of thousands of miles of hole-filled paper.

There is a certain layered, geological dystopic quality to the images of these men laboring at producing piano rolls for player pianos (and found in The Illustrated London News for 18 December 1909). This is true especially for the details, the small boxes in the background to where the rolls are being "processed"--music pounded out with metal points on a hard surface, as though produced by whatever it was that was in those little labeled wooden containers, far removed from the artistry of melody. These are images of a culture being made into hundreds of thousands of miles of hole-filled paper.

The piano roles remind me of automatons replacing humans in entertainment, and then replacing the humans making the piano roles; of machines taking over the jobs of people writ large. There's a long and rich literary history of this idea, not the least (or first) of which is the appropriately-named Player Piano, Kurt Vonnegut's first novel, written in 1952. Like a tiny idea-machine, Vonnegut manufactured part of his tale from Brave New World, with Huxley having taken his bit from an earlier novel, We, written by Yevgeny Zamyatin in 1921--they're all bleak images of a future dominated by machines, the humans acquiring numbers for names, like the replaceable and expendable units they became.

(Artwork by Malcolm Smith for Imagination, June 1954.)

The devices for producing the roles remind me of Jeremy Bentham's panopticon, a functional prison designed so that all of the prisoners could be viewed from one central point. The profile of the place reminds me of the geared punch machine for the piano roles; I'm not at all sure about what the function of the prison reminds me of. But in the history of holes, I guess all it foes it fill u its empty holes with people, keeping them there for months or years or decades, and then replacing them with other people, part of a long and continuing series.

Here's the panopticonal prison at Presidio Modelo, Isla De la Juventud, Cuba--with the walls laid flat, and some cells filled-up, and reduced, you may be able to make a certain music with it, like reading the scores made by pigeons roosting on a five-wire-strung staff of utility poles. My daughter Emma just suggested that there could be a Morse Code crossover as well!)

The plan and elevation of these prisons relate to the player paino paper, like the early dots and dashes of communication, like the punched cards that Vonnegut had in mind when he was writing his early classic.

Now, the rest of the Illustrated London News story (available here on my blog bookstore):

JF Ptak Science Books Post 1227

[Click image to enlarge; both original images are available for purchase from our blog bookstore.]

[Click image to enlarge; both original images are available for purchase from our blog bookstore.]

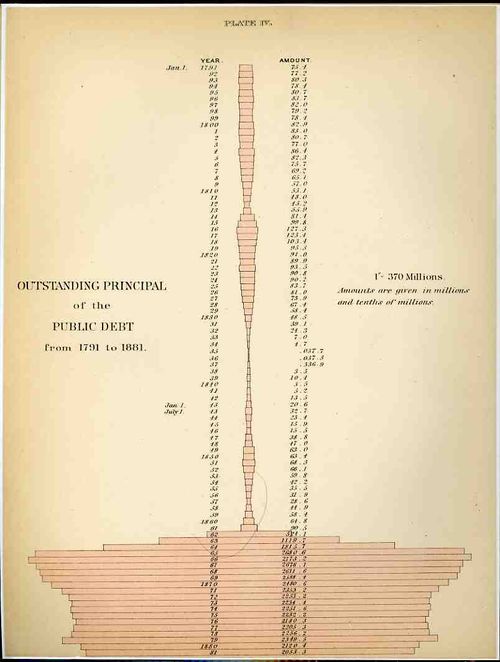

It isn't often that you see money represented by dry measure, but that's what happened here in these two examples from the fantastic Walker Statistical Atlas ( Statistical Atlas of the United States based on the results of the tenth census 1880 with contributions from many eminent men of science and several departments of the government Comp. under the authority of Congress by Francis A. Walker, M. A., superintedent of the tenth census ... and published in 1884). What we see here is a history of American federal indebtedness from 1791 (when the public debt stood at 75.1 million dollars) to 1881 (about 2 billion). Using the CPI (consumer price index) as a factor to translate that number in 2008 dollars (or so), the 2 bil grows to about $40 billion (a nickel then is about a dollar now). The interesting part of the legend--and what drew me to this graphic even before its somewhat unique shape--state "1"--370 millions", that is one inch of pink horizontal bar stands for about $370,000,000, and the last bar on this graph is about 6 inches long, which, adjusted for inflation, would now be about 10 feet long. .That said, the really interesting part comes next--if we use this measure to graph a horizontal bar for the American debt as it stands in 2008, it would pink a pink bar that was about a HALF MILE long to express our 10(+) trillion dollars of debt. OR, somehow, the old debt of 1881 would be about 1 story of a house, while the 2008 version would be up one side of the Empire State Building and down the other (and yes that includes the aerials). I don't know how to put this comparison in context, the differences are so staggering.

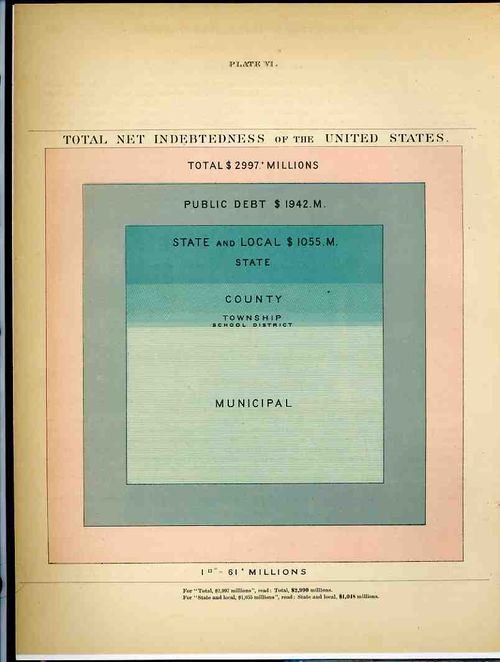

After having popped a neuron or two trying to get my head around that one, we'll further confuse the situation with the second chart, which shows the total net indebtedness of the U.S. in 1881 in terms of square inches; or, at the bottom of it all, a 7x7 inch square represented the entirety of the $3 billion owed out. 49 square inches. Working backwards this time, our $10 trillion (or $10,000,000,000,000.00 writ large) adjusted back to a CPI value in 1881 would have covered about 88 PAGES of the atlas or 9,000 square inches. Again, the numbers are just almost too big to mean anything.

We, as a country, owe one hell of a lot of money.

And yes there are many different ways of trying to figure out what one 1881 dollar "means" in terms of 2008, but the CPI is the most simple to use and least argumentative and at least gives a pretty good idea of scale. It would be more useful to try and establish the degree of difficulty of turning the corner on the debt in 1881 compared to doing that today, but this is just a late-night post at the end of the week, and I don't have a good clue about how to try and measure that bit simply.

Posted by John F. Ptak in Absurdist, Unintentional, Blank and Empty Things; A History of, Economics, History of the Future, Information, Quantitative Display of, mathematics, logic | Permalink | Comments (0) | TrackBack (0)

Tags: display of data, economics, statistics

JF Ptak Science Books Post 1225

"But with regard to the material world, we can at least go so far as this—we can perceive that events are brought about not by insulated interpositions of Divine power, exerted in each particular case, but by the establishment of general laws." W. WHEWELL: Bridgewater Treatise.

"To conclude, therefore, let no man out of a weak conceit of sobriety, or an ill-applied moderation, think or maintain, that a man can search too far or be too well studied in the book of God's word, or in the book of God's works; divinity or philosophy; but rather let men endeavour an endless progress or proficience in both.." BACON: Advancement of Learning.

The quotes above stand alone, the first things that the readers see, sitting on the half-title page of Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species (first published in 1859 in an almost-immediately sold out run of 1250 copies) an extraordinary, epochal book that was a lightning rod for reception both good and bad, heaven and hell, the Boschian hells of which were clearly not deserved, then or now. (It is easier to understand a poorly-reviewd Origin in 1859 or through the 1860's or even through the rest of the 19th century or even somehow through the early twentieth, but not afterwards.)

Twelve years after the first edition of the Origin (and two years after the appearance of the Origin in its fifth edition) came his elegant and formibible The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex

The Times of London gave such an awful review of the book that a review of this review was published in the April edition of Nature [(Darwin), Charles. REVIEW of Review: The Descent of Man. London: Nature, 1871, volume 3, 20 April 1871]. It was Thomas Stebbing who wrote the response to The Times' incitful, hateful attack upon the Descent of Man. The Times saw Darwin's work as an attack upon society, accusing him of undermining authority and principles of morality, opening the way to "the most murderous revolutions". A "man incurs a grave responsibility when, with the authority of a well-earned reputation, he advances at such a time the disintegrating speculations of this book." Stebbing's review of the review is drippingly sarcastic, pointing out obvious errors in specific and the tone of the article in general in the defense of the book. Darwin's "facile method of observing superficial resemblances" (says The Times) incites Stebbing to issue the following: "they may fancy that truth is worth discovering , even when it seems to involve some contradictions to our pride and some loss of comfort to our finer feelings..." (What a great line!) The article runs about 1000 words, and is a two-column, 1-page bit. [This issue of Nature may be purchased from our blog bookstore, here.]

"No one ought to feel surprise at much remaining as yet unexplained in regard to the origin of species and varieties, if he makes due allowance for our profound ignorance in regard to the mutual relations of all the beings which live around us." Darwin, leading the last paragraphs of the end of the introduction to the Origin, page 7.

Posted by John F. Ptak in Absurdist, Unintentional, Bad Ideas, Blank and Empty Things; A History of | Permalink | Comments (0) | TrackBack (0)

Tags: Darwin, Descent of Man, Evolution

JF Ptak Science Books Post 1217

[Also see my post on producing the geometrical man "Durer's Beautiful Monster", here.]

I’ve written earlier in this blog about the advent of robots and human machines, and I’d like to add these two images to that thread. Both are male, which is not horribly surprising since the earliest creation of a female robot belongs to the fertile Fritz Lang, who used his creation in his extraordinary movie Metropolis in 1927. (Male robot-like creations go back fairly deeply into the 19th century; so perhaps the creation of female robots was verbotten because of the possibilities for unacceptable sexual fantasies in the high- and post-Victorian world, struggling under the weight of many and multiply-applied public inhibitions. Perhaps it was because of the possibility of sexual relations with an inanimate object that was the cause for one-gendered robots, or perhaps it was a fear of a powerful, intelligent, unstoppable, superior creation that was also “womanly”. I don’t know.)

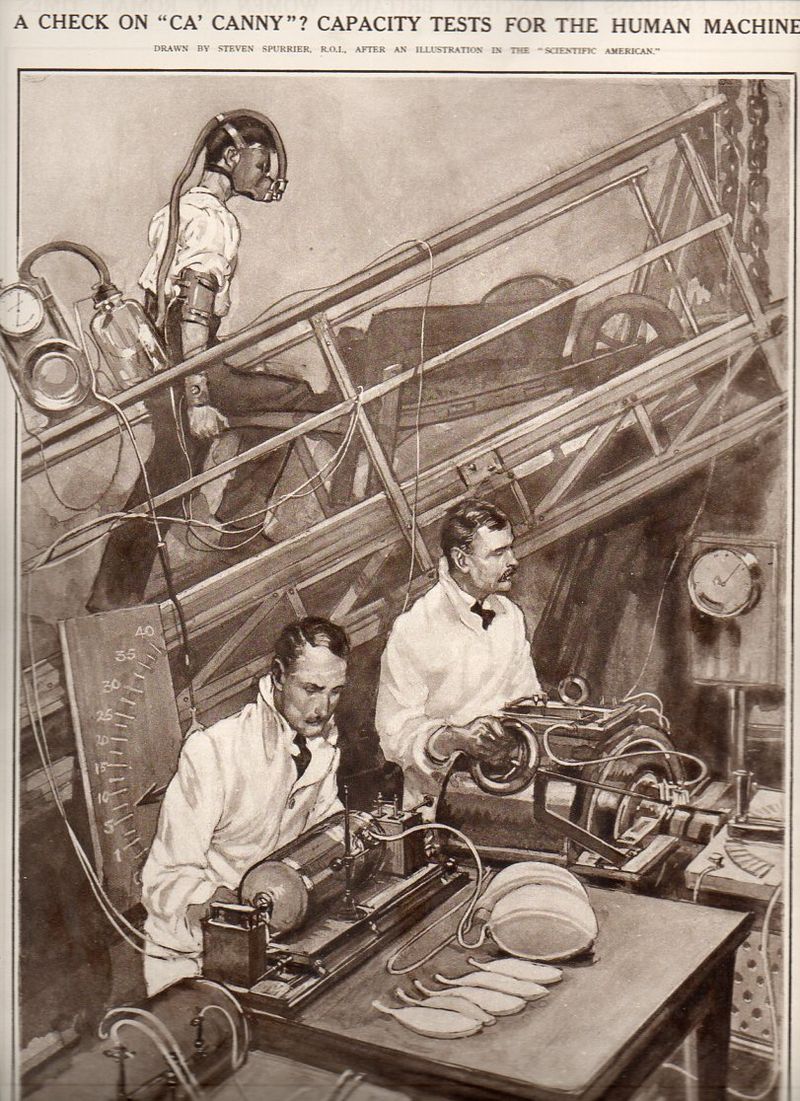

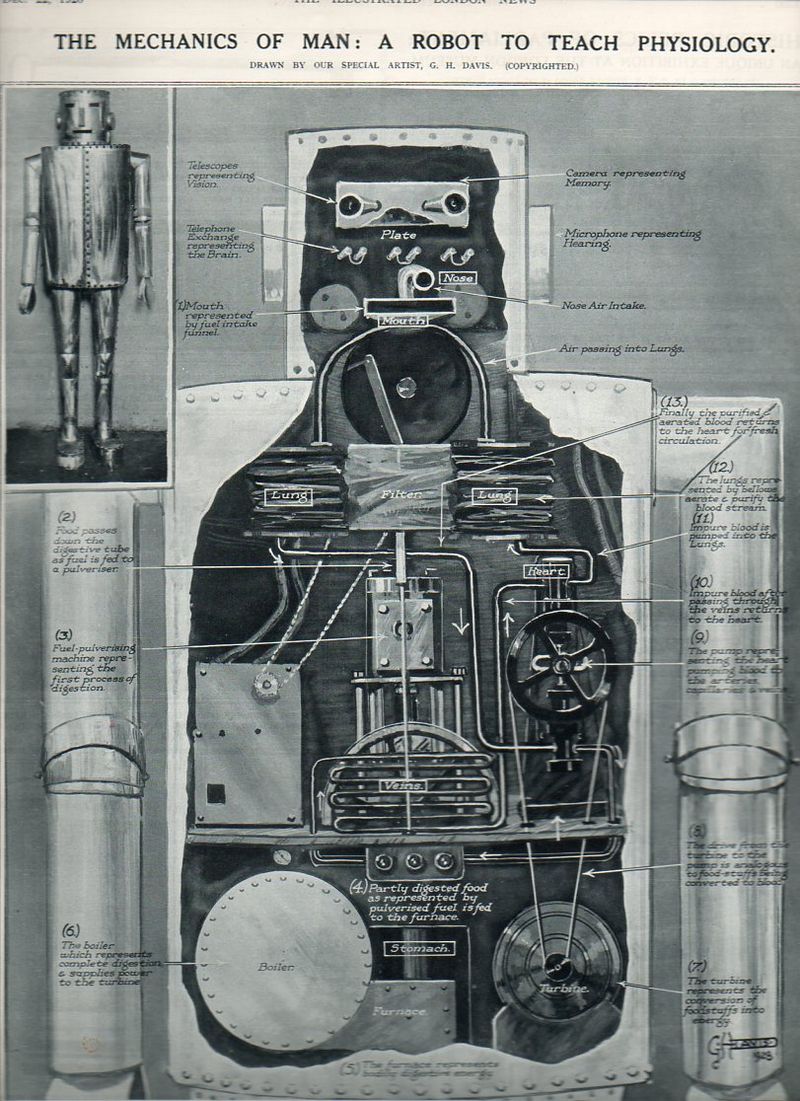

[Both of these images are available from our blog bookstore.]

The first is an image of the “human machine”, a cog-like adaptation of human workers in a Frederick Taylor-like The Principles of Scientific Management study, automatizing and industrializing people. Though many people had written and worked around Taylor’s 1911 semi-revolutionary book (and not necessarily a good revolution, but one nevertheless), I’m not certain that I’ve seen the worker trussed up so before this, encumbered by so many technical testing elements as to make him look like a cyborg (though that term would still be a while coming into the vocabulary.

This image is actually testing a person’s energy expenditure while pushing a wheelbarrow on an incline, and utilizes the newly-created equipment of the French physiologist Langlois, which in 1921 may well have measured for the first time the real-time changes in the rhythm of the heart and blood pressure, changes in body temperature and lung capacity of humans in an activity. I have no doubt that the results would have been very interesting to cardiologists, and probably didn’t mean a thing to industrialists like Henry Ford, who would’ve plowed ahead with their demands on their workers regardless of what tests said, schedules being schedules and all.

(I’m no tsure where this experiment fits in, historically speaking, even within the context of biological advances for that very year. Frederick Banting was able to do some pretty nasty stuff to dogs in a basement lab somewhere at the University of Toronto and come up with a successful treatment for diabetes mellitus–insulin, which would save the lives of millions and earn Banting a Nobel two years later. In the quasi/fake biological arenas came two biggish events: Jung’s creation of the concepts of introvert and extrovert, and Hermann Rorschach’s one-way conversational device for detecting psycho-pathological conditions (in people). I suspect that the Langlois data would fit in there somewhere along the rough edge of Jung and Rorschack, if only because the data was real.

The second image is in a way a reverse sequence of the preceding–an out-and-out robot that was being used to teach human physiology. In this case, the robot was a steam engine, constructed for the Schoolboys’ Exhibition at the New Horticultural Hall for 1928, perhaps under the influence of Karel Capek’s newly published drama R.U.R., which coined the term “robot”. The biological functions of humans were reinterpreted along a more user-friendly vocabulary of the steam engine, using pumps, boilers, hinges, belts, pulleys, filters, compressors and a furnace to explain the functions of respiration and circulation. It was an interesting approach to show these functions on their most basic level–and in less than 75 years, many of these mechanically represented organs were actually replaceable by real mechanical units performing the same task as the biological (as in the heart), while others could be replaced (via transplant).

Man as machine and machine as man.

Posted by John F. Ptak in Absurdist, Unintentional, Bad Ideas, Militaria, Perspective, Technology, History of | Permalink | Comments (0) | TrackBack (0)

Tags: Cyborg, Kapek, R.U.R., Robots

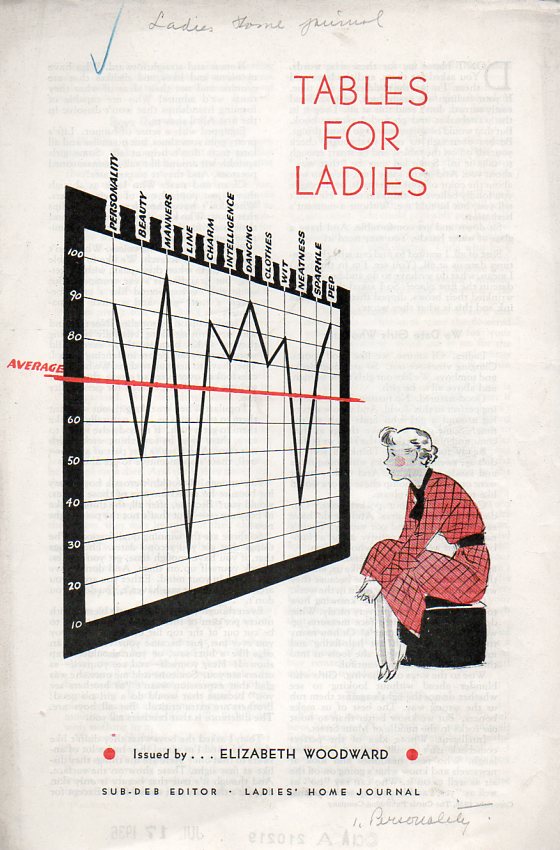

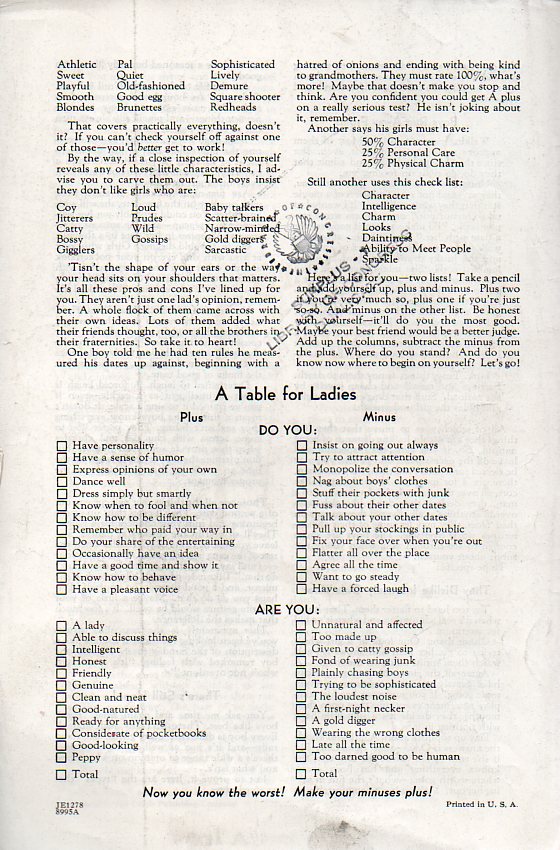

JF Ptak Science Books Post 1211 I must admit that I like the first of these two “lady tests” (separate publications from The Ladies Home Journal), cautionary tales as they are, like being able to select your own villainous wardrobe for a creepy (or loud or not) 1940's version of a Brother’s Grimm fairy tale--instructive, occasionally delightful, often wincing. It seems that the dividing line between being particular and being peculiar displays its fair share of the miracle of capilary action.

I must admit that I like the first of these two “lady tests” (separate publications from The Ladies Home Journal), cautionary tales as they are, like being able to select your own villainous wardrobe for a creepy (or loud or not) 1940's version of a Brother’s Grimm fairy tale--instructive, occasionally delightful, often wincing. It seems that the dividing line between being particular and being peculiar displays its fair share of the miracle of capilary action.

For example, in Tables for Ladies (1936), the failing grades (minuses) actually look mostly like, well, problematic personality quirks. I get the “too made up”, “late all the time” and “gold digger” parts–also the character who has a forced laugh, agrees all the time, and is endlessly flattering while putting on makeup and pulling up stockings and monopolizes the conversation (simultaneously?)–and then wants to “go steady” right away while complaining about her (and his) former dates, does not make for an interesting time out. [Both Tables for Ladies and How Ya Doin' are available for purchase at our blog bookstore.]

I’m not sure what “too darned good to be human” and “occasionally have an idea” mean, nor the failing grade for having too much stuff in your pocket. A lot of the other stuff looks okay to me: intelligent, honest, friendly, genuine, good natured–basic things that translate just fine into 2010. But then there are those servile, squinty-eyed parts that just give you a coppery feeling in your mouth for how restrictive they are.

Of course there’s stuff there indicative of the time, just like the awful racism that creeps into Babar or Bugs Bunny from th 1940's, or the rank use of racial epithets that populate some regional maps of the south (I can easily attest to the very broad use of the n-word in more than a dozen places in a large 1932 map of my own Buncombe County, all gone today), or the portrayal of subservient women in 1950's common culture–but for the most part, the overall reach of this little pamphlet seems not-terrible.

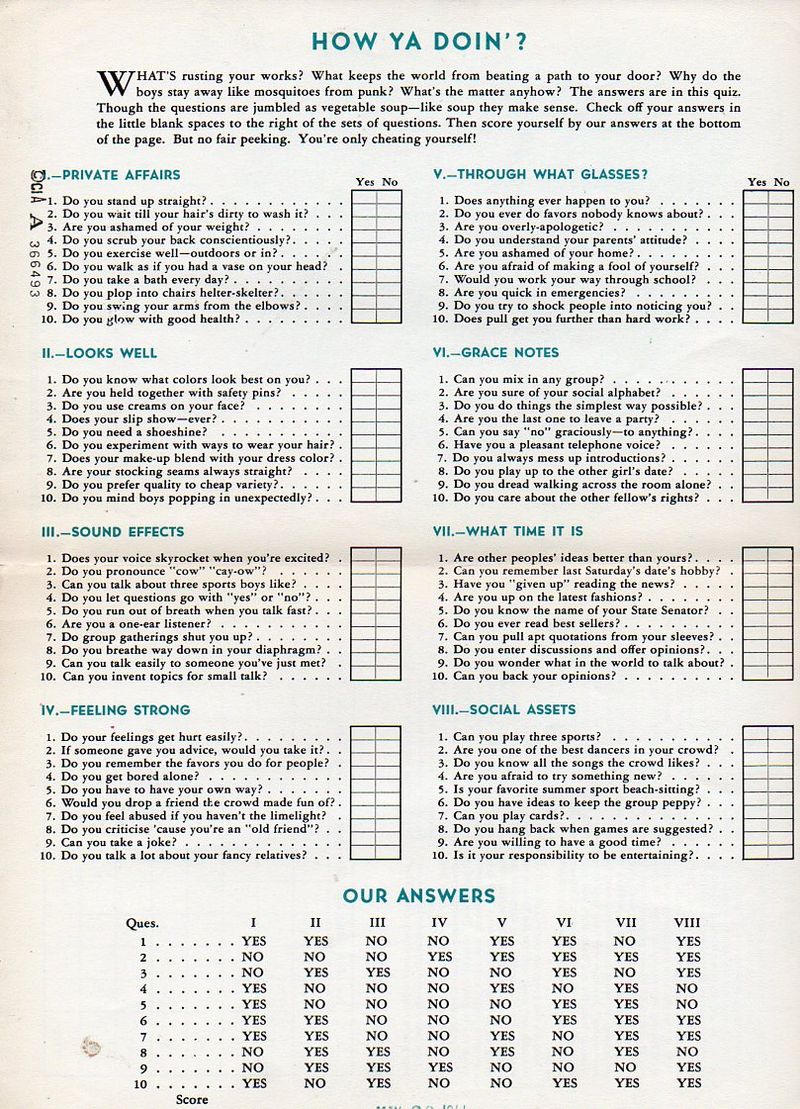

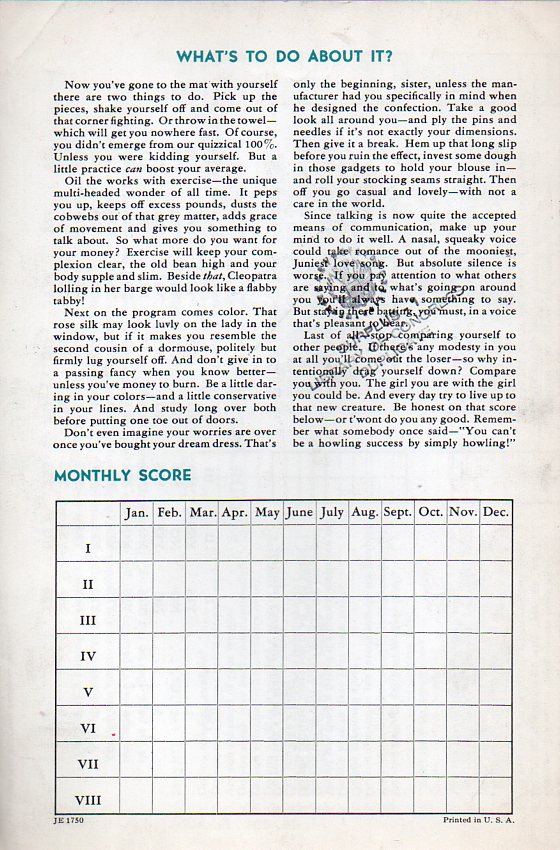

The second little test, How Ya Doin’ (1941), verges more on the need for the mass produced Stepford woman, only this one comes from an earlier period, the mother of Stepford. Some number of the questions seem less significant but more important, many feeling annoying and trite--many of the graded areas are so unexpected (here in 2010) but were in 1941 thought of as being socially important and, well, marketable.

The second little test, How Ya Doin’ (1941), verges more on the need for the mass produced Stepford woman, only this one comes from an earlier period, the mother of Stepford. Some number of the questions seem less significant but more important, many feeling annoying and trite--many of the graded areas are so unexpected (here in 2010) but were in 1941 thought of as being socially important and, well, marketable.

It was important to say "yes" to the questions "do you scrub your back conscientiously?", "do you walk as if you had a vase on your head?", "does your make up blend with your dress color?", "are your stocking seams always straight?", "can you talk about three sports that boys like?", "do you breathe way down in your diaphragm?", "does anything ever happen to you?", "can you play three sports?", "do you know all the songs the crowd likes?", "is it your responsibility to be entertaining?", and so on.

Not all of the questions feel so sharp and stinging--there are many good qualities (or good qualities from the 2010 mind) that are listed here as well--not to abandon your friends, believing in yourself, inspecting and supporting your opinions, knowing how to decline graciously, feeling good about where you live, being kind, expressing concern, and the like.

The quizzes are not without quality.

In the same vein you might also enjoy these earlier posts in this blog

What Goes into Making Human Robot Girls

How to Look Smart, or Pretty, but Not Both

Maintaining Women as a Subclass: Major Reinforcements from Minor Non-sequitors

Missing Pieces of Women: Pope Joan and the Proper Girl of the Ladies Home Journal

How FDR Made Women (1) Nervous and thus (2) Older. An Appeal to Vote Republican, 1936

Posted by John F. Ptak in Absurdist, Unintentional, Bad Ideas, Women, History of | Permalink | Comments (0) | TrackBack (0)

Tags: feminism, history of women, Women

JF Ptak Science Books Post 1208

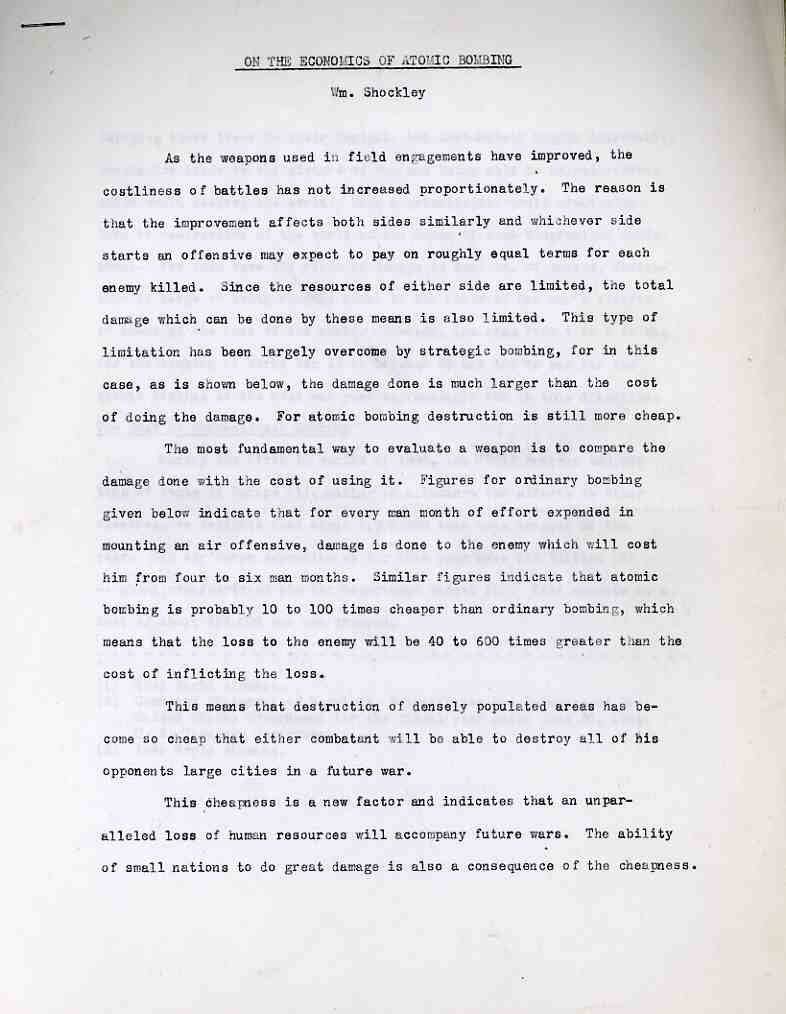

This paper is one a small archive of background and draft papers and proposals by the Vannevar Bush group working on the question of the control of atomic weapons and the formalization of the American position regarding the use and control of atomic weapons, October 1945-February 1946. This archive consists of 38 documents relating to the development of U.S. atomic policy, with contributions by President Harry Truman, Secretary of State James Byrnes, Dr. Vannevar Bush, (future AEC director) Carroll Wilson, Alger Hiss, I.I. Rabi, William Shockley, Frederick Dunn, Joseph E. Johnson, Leo Pasvolsky, Philip Morrison, Col. Nichols, William McRae, Admiral W.H.P. Blandy, George L. Harrison, and others.

I have written elsewhere on this site about Vannevar Bush and the coming atomic/nuclear arms problem--as perhaps one of the pre-eminent scientific minds in the Roosevelt/Truman administrations, Bush and others foresaw the development of the atomic arms race in 1943, and by 1945 Bush became a fundamental thinker and advocate on the problem. The items in this archive are low-formal background papers, drafts of proposals, informal studies, as well as mature statements of thought that would become implemented in the core of U.S. policy regarding the spread and control of atomic weapons. They are generally carbon typescripts and necessarily of extremely limited distribution, generally have no letterheads, occasionally carry the authors’ full names (although sometimes only initials are used).

The William Shockley paper was written towards the end of 1945 and is on five pages and runs about 1500 words, and is an extension of work he had already been doing for Henry Stimson with Quincy Wright on evaluating the combinations of casualties that would lead the Japanese to surrender3. He begins this paper with a logical statement of the issue of the economics of conventional and atomic bombing, ending with the sentence “For atomic bombing destruction is still more cheap”. What Shockley is getting to is the overall cost of the amount of destruction caused per square mile, and the conclusion that he draws over these five pages is the destruction caused by the atomic bomb is 1/100th the cost of conventional bombing per square mile destroyed (“atomic bombing is probably 10 to 100 times cheaper than ordinary bombing”).

Shockley also recognizes that the problem in the near future will be the increasing cheapness of producing atomic (and greater) weapons, and their developing accessibility to small nations. “This cheapness is a new factor and indicates that an unparalleled loss of human resources will accompany future wars. The ability of small nations to do great damage is also a consequence of the cheapness.” He writes further that taking this thinking to its “logical conclusion”, that at some point in the future a single individual will be able to use this new technology to destroy the world. The main point though that he was making in this line of thinking was the dispersion and proliferation of the new technology--that an arms race would occur, and that it would be dangerous, and that it could be very very bad. Shockley has of course nothing to say about any of that or the implications of his finds as that was not his charge.

After figuring that the cost of destruction by the atomic bomb was about $600,000 per square mile (compared to $6,500,000 per square mile for conventional bombing), Shockley concludes that “since the atomic bomb art is in its infancy, we may well expect future economies of a factor of 10 in cost per square mile destroyed…”

Shockley on the likelihood of casualties during the final invasion of Japan.

(The following three paragraphs are taken entirely from CASUALTY PROJECTIONS FOR THE U.S. INVASIONS OF JAPAN, 1945-1946: PLANNING AND POLICY IMPLICATIONS by D. M. Giangreco in the Journal of Military History, 61 (July 1997): 521-82

“As for Dr. Shockley's initial report to Dr. Bowles, it was not submitted until after Stimson had left for Potsdam. He proposed that a study be initiated "to determine to what extent the behavior of a nation in war can be predicted from the behavior of her troops in individual battles." Shockley utilized the analyses of Dr. DeBakey and Dr. Beebe, and discussed the matter in depth with Professor Quincy Wright from the University of Chicago, author of the highly-respected A Study of War; and Colonel James McCormack, Jr., a military intelligence officer and former Rhodes Scholar who served in the OPD's small but influential Strategic Policy Section with another former Rhodes Scholar, Colonel Dean Rusk. Shockley said:

"If the study shows that the behavior of nations in all historical cases comparable to Japan's has in fact been invariably consistent with the behavior of the troops in battle, then it means that the Japanese dead and ineffectives at the time of the defeat will exceed the corresponding number for the Germans. In other words, we shall probably have to kill at least 5 to 10 million Japanese. This might cost us between 1.7 and 4 million casualties including [between] 400,000 and 800,000 killed."--W. B. Shockley to Edward L. Bowles.2 .

No accurate total of German military and civilian deaths was available at the time he prepared his report, but the number was eventually set at roughly 11,000,000. was not invaded and finished the war with just over 7,000,000 casualties, most of them from its armed services on the Asian mainland in fighting from September 1931 to September 1945.

Notes:

1. The brilliant Shockley’s story is difficult and problematic: from the way in which he misused his interaction with the rest of his team at Bell Labs in the discovery of the junction transistor to his sinful racial and eugenic (and dysgenic) public persona later in life--it is a hard and long one to tell, and I’ll not try to do it here. (I should point out that his attacks started in 1966 when he "delivered the first of a series of controversial papers to the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) in which he called for a renewed focus on racial biology, synthesizing under the title of eugenics the compulsive element of population control with the targeting of the dysgenic fertility of the black population".[From “Confronting the Stigma of Eugenics: Genetics, Demography and the Problems of Population” by : Ramsden, Edmund in Social Studies of Science, Vol: 39 Issue: 6, 12/2009 pages: 853 - 884.] Suffice to say that I’m very aware of the very long shadows, and I think that other people should at least be aware of them as well, regardless of the staggering importance of “his” (with the wonderful Walter Brattain and John Bardeen) monumental discovery.

2. 21 July 1945, "Proposal for Increasing the Scope of Casualties Studies," Edward L. Bowles Papers, box 34, Library of Congress.

3. For a detailed look at Shockley's work in this area see Predicting the Termination of War: Battle Casualties and Population Losses, by Frank Klingberg in The Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol. 10, No. 2 (Jun., 1966), pp. 129-171. Dr. William B. Shockley (later a joint winner of the Nobel Prize for his work in developing transistors) was an expert consultant to the Secretary of War, engaged in part in gathering and organizing information bearing on the problem of casualties in the Pacific war. He believed that historical studies of casualties might be helpful &dquo;for consideration in connection with the total casualties to be expected in the Japanese war, the rate at which land invasion should be expected in the Japanese war, the rate at which land invasion should be pushed

ahead in Japan or held back while attrition by air and blockade proceeds, and the relativeapportionment of effort between the Army Air Forces and the Army Ground Forces..."

Posted by John F. Ptak in Absurdist, Unintentional, Atomic and Nuclear weapons, Militaria, Technology, History of | Permalink | Comments (0) | TrackBack (0)

Tags: atomic bomb, nuclear war, Vannevar Bush, WIlliam Shockley

JF Ptak Science Books Post 1206

Self- and purposefully-deceptive belief in spectacular and unsupportable scenarios espoused by governmental leaders which affect the lives of hundreds of millions of people deserve their own Dante-esque categorization: and that’s one that I haven’t come up with yet. This post is one of a continuing thread on the history of atomic weapons. {Incidentally, the pamphlet described here is available for purchase from our blog bookstore, here.]

I wonder how it was that we humans didn’t blow ourselves into melty dissolving bits during the Cold War. Somehow all of those thousands of megatons of disastrously radioactive explosives that were completely and reliably deliverable didn’t get launched—not even by accident, not even during all of those hot itchy-finger DEFCON 2 situations. Did MAD (Mutually Assured Destruction ) actually work? Did the attempt at making a winnable nuclear confrontation keep people from actually trying to do so? Did the overwhelming and insane buildup of weaponry actually have so much enormous and foul intellectual weight that no one could actually make the decision to use the weapons for fear of snuffing out all human life?

Here’s an embarrassingly shining case in point: Dr. Joseph D. Coker’s paper to the Population Association of America representing the thinking of the Office of Emergency Planning and the Executive Branch in general, which freely discussed the survivability of the United States following even a post-massive nuclear exchange. Dr. Coker was the director of the National Resource Evaluation Center, which tried mightily to figure out how/where /what/how the essential 'stuff” of America could be saved/stored/allocated after the end of the world. Actually, Dr. Coker said that the big attack wouldn’t be the end of the world, so we needed to plan for surviving.

A few cases in point, some of which, I must warn you, are breathtaking and Strangelovian in their myopia:

Since Dr. Coker was addressing the Population Studies people, he related much of what he had to say (regarding national resources) to the American people. He found that millions of people could be saved if they built a blast shelter (not a fallout shelter) that was covered with mounds of heavy material and outfitted for an extended stay of two to 22 days. The unfortunate part of this scenario, Coker says, is that these shelters work best when 10 miles or more away from a detonation zone. And since these zones were all over the country targeted by thousands of warheads, very few people (especially in cities) would be outside the 10-mile ring, which made the blast shelter basically useless.

Coker notes that if an attack of 1000 megatons [a limited exchange] was aimed exclusively at U.S.air bases, “total fatalities will approximate 10% of the U.S. population”. If this attack was aimed at population centers rather than the air bases, it would kill 40% of the population. A 5,000 megaton attack on air bases would produce 50% overall fatalities in the U.S.; if that amount was centered on large populations, the number would jump to 80% of the population. 10,000 megatons would yield 75% and 95%, respectively. “A 50,000 megaton attack would kill almost all U.S. citizens under either targeting assumption”. These figures didn’t include radiation deaths.

A big variable here not controlled for was the distribution of population at the time of attack. The numbers that were used were compiled by the census and counted folks who would be at home. So, the numbers above worked if and only if the Soviets attacked after dinner when everyone was at home for the night. Since it would make sense to attack when people were at work at their industry or job or whatever during the day—thus maximizing the effect of the bomb—the casualties would actually be higher.

And what does that mean? Dr. Coker relates this gem (on page 21): “The post-attack labor force available thirty days after the attack probably will represent a significantly lower fraction of the population than does the preattack labor force….” And this: “A nuclear attack can be expected to alter the occupational composition of the labor force.”

This sort of thinking overtakes the factual aspects of massive attack, with Coker stating on page 24 “I wish to say emphatically that it [post-attack America] will not be anything like that depicted in Neville Shute’s On the Beach. It will be bad enough, but not that hopeless.”

And this absolutely incredible/horrendous and perhaps worst-use-ever of the word “awkward”:

For the love of King Neptune’s Pants: Awkward? How in the name of _______ could someone in such a high position and authority relate massive attacks on every major American population center which would cover the area in fire and thousands of gigantic highly radioactive craters in which a city used to exist be called “awkward”? How great a sin was this, to influence opinion on holocaust via pathetic and unreasonable means?

And then this, on the survivability of our governmental and economic institutions:

“The post attack institutional environment will depend on the continuity, resourcefulness and general effectiveness of our leadership and the survival and resilience of pre-attack institutions…”

Hm? The post-attack institutions will depend on themselves?

This of course is followed by a major plug for Dr. Coker’s own work, because the preparations undertaken by the NREC will directly affect the survivability of post-attack America. So don’t stop the funding. “The more complete and realistic our preattack [sic] planning and preparations have been and the more effectively the government is at all levels in inspiring and retaining the confidence and support of the population, the less drastic institutional changes will be.” So it is the mealy aspect of inspiration that will direct the survivability of whatever it is that makes America so.

I should point out that Coker’s use of “post attack” and “pre attack” appear as two words, one word and a hyphenated word, depending on nothing. This is only a forty-page document.

Another nugget on the post-Armageddon future on the distribution of wealth, mostly hinging on blast shelters: “Per capita wealth in material terms may or may not be reduced by attack.” There will be a relatively proportional number of people who emerge from the smoking holes to staff surviving industry, and so per capita wealth will stay about the same. If, on the other hand, people build more blast shelters, then the proportion of surviving workers to factories will increase, and “the surviving plant capacity will be spread more thinly among them”. It is left unstated, but what that means is that more successful implementation of blast shelters would mean a reduction in per capita wealth. Dr. Coker also forgets what he said earlier that the blast shelters really didn’t work unless they were more than ten miles from a target. Considering that the industrial workers would be living close to, um, industry, they will no doubt be (in 1962) in a ten-mile radius to where the blast would be. Then of course there would probably be more than one bomb, so the blast area would be more than a ten-mile circle, and so on and so forth.

In the following paragraph, Dr. Coker somehow draws all manner of feel-good high-probables around him, encasing himself like a sandman in a thin layer of improbability, to come to the following conclusion:

“…few of the analysts who have studied carefully these post-attack [sic] survival and recovery problems take any stock in the oft-repeated theory that the survivors will envy the dead. On the contrary, after a very rough year or two, the surviving population, if it so chooses, can begin to enjoy the advantages of a social structure and a physical environment not so very different from those which prevailed before the attack.” [Emphasis mine.]

This is an astonishing work of incredible deceit, and may be the worst quote of the lot. But it is so difficult to choose between unacceptable bits of thinking like this, raking out the horrible from the terrible.

Here’s another deceit that was absolutely better understood in 1962 than the writer acknowledges: “The long-term effects of radiation are subject to much less understanding and certainty than are the short term effects. There is some evidence that increased radiation exposure results in reduced life expectancy and increased evidence of leukemia and various degenerative diseases…” And this: “Genetic effects are more controversial.” Than what?! And this: “Studies of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki experience are said thus far to be inconclusive.” Honestly this was very well understood in 1962, and statements like these were enormously irresponsible if the data were actually misunderstood and criminal if they weren’t.

There are many more examples—I’d say actually that the entire paper was at the level of Apocalypse Fairy Tale—but I’d like to close with just one more, this one using another fanciful version of the possible post-nuclear future and another highly insulting euphemism. On transportation: “We hope in the near future to develop a family of network and transportation models to estimate capabilities to move surpluses into deficit areas in order to cover deficits during each time period and to support the use of more ambitious resource management techniques focussed [sic] on recovery problems.” Aside from bad sentence structure and misspellings I could hardly imagine sitting through a presentation where a person thought this stolen undercooked tripe. What we have arrived at here at the end of the paper is references to smoke-in-a-hole cities being “deficit areas”, and the successful removal of human consideration from the conversation—strange as Dr. Coker was addressing the Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America. (I’d love to know what the association members thought of the talk afterwards.)

And so what can we draw from the experience of knowing thinking like this? Is it as sterile as it might seem, so distant from our experience? The scenarios have changed, as have the leaders and delivery systems, but the insatiable stupidities have evolved and morphed into our own time. Its easy to raise our eyebrows now on the whole MAD approach and the writings of people like Dr. Coker. The truth of the matter is that we have plenty of this sort of thinking going on right now, big head-waggers that will loom in our futures with the attached questions of “how could this have happened?”. WMD is one of the many examples of this, a Big Lie that was repeated for years and which ultimately cost the lives of many thousands of people and a great perpetuator of the culture of fear. President Bush drove that one into the ground and so far as I know still employs it when necessary, threatening listeners with fear of those three letters like they were a practice hand grenade. (I recall that a far-right radio personality filled with afterbirth blood and urine eyes said that he would resign his show “in a year” if WMD were not found in Iraq; that was five years ago, and of course he is still there, bloated and ponderous and mostly violently wrong as ever.) The Savings and Loan debacle. The deathly ambitious practices leading to our recent depression. The billion malnourished and desperate children in the world. And so on. The point is that there is no paucity of thinking displayed by Dr. Coker in the past, and there is definitely no lack of it right at this very moment. The problem is seeing it for what it is in the present and to not have to wait for the future to get to the truth of the matter.

[And how can I end this discussion without a bit more of Stanley Kubrick's magnificent Dr. Strangelove.., who pointed out these absurdities better than,perhaps, anyone?]

Ah, don't fret! The ending is just below (and just when you are about to laugh ("Mein Fuhrer, I can WALK" the other and last shoe drops.).

Posted by John F. Ptak in Absurdist, Unintentional, Atomic and Nuclear weapons | Permalink | Comments (1) | TrackBack (0)

Tags: armageddon, Atomic bomb, Coker, MAD, nuclear weapon

JF Ptak Science Books Post 1204 [Part of our Bad Ideas series.]

Sometimes things aren't what they seem, and then sometimes they're not what they seem not to be, and then there are these things, below. These small pamphlets are very reaching examples of finding gold or silver or muffins or whatever in a sow's ear, finding a hope for belief where there wasn't room for any, logically speaking. But there's always room for belief and faith, which takes on myraids of appearances, from believing in paper money to believing in heaven--in these cases, our writers believed in the unbelievable, creating and then believing in "innermost secrets" where there were no secrets and were no insides.

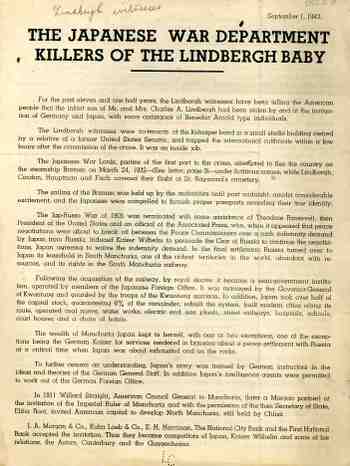

Both of the examples below relate to the kidnapping of the 20-month-old son of Charles Lindburgh in 1932. The crime was an extraordinarily national event, with seemingly everyone in the country following the case During the two-month hunt for the baby and the subsequent trial and execution of the man who was seen as responsible for the child's kidnapping and murder, there were fantastic numbers of claims from people who had solutions to the mystery, or had been in contact with the kidnappers, or some other sad, imaginary relationship to the event. The examples below [both of which are available for purchase at our blog bookstore] claim to have incredible insight into the real nature of the crime, which of course goes blindingly beyond the simple matters of the case and on to include massive colusions between the U.S. State and Justice Departments, "international bankers", F.D.R., Kaiser Wilhelm, and "the Japanese government". And more.

The first example was published in 1942 by something called "The Mothers and Daughters Committee". This group used the address of 280 E. 21St Street, Brooklyn, New York, which today is a six storey building with 96 apartments, and I suspect that the MADC back there in '42 was nothing more than a crank in apartment inthis building. The thinking is too confusing and the references too many amnd too busy to actually do this thing justice by de-threading it, but suffice to say it claims that the F.B.I. was shielding "the international criminals"who were truly responsible for the crime--I'm not sure how F.D.R. works his way in there but it has something to do with "international bankers", communist conspirators, traitors in the State Department, and "needy" lawyers, all brought together in a choking confluence to do harm somehow to American society and morality.

Now our second towering example is this four page pamphlet, received by the Library of Congress (and probably nobody else) on 1 October 1943, which divines the origins of World War Two and the kidnapping of the Charles Lindbergh baby to a complex and impossible cabal of Japanese “War Lords”, Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany, the assassination of Leon Trotsky, the League of Nations, Elihu Root, “3 cent gallon kerosene”, the South Manchurian Railway, and some sort of “historical documents of posterity countersigned by Tokyo and Berlin” in the possession of Mrs. Renee Valentine (“Secretary”) of Staten Island, New York.

Now our second towering example is this four page pamphlet, received by the Library of Congress (and probably nobody else) on 1 October 1943, which divines the origins of World War Two and the kidnapping of the Charles Lindbergh baby to a complex and impossible cabal of Japanese “War Lords”, Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany, the assassination of Leon Trotsky, the League of Nations, Elihu Root, “3 cent gallon kerosene”, the South Manchurian Railway, and some sort of “historical documents of posterity countersigned by Tokyo and Berlin” in the possession of Mrs. Renee Valentine (“Secretary”) of Staten Island, New York.

The entire affair began with “co-tenants of the kidnappers band in small studio building owned by a relative of a former U.S. Senator” under the instigation of “Germany, Japan and certain Arnold Benedicts types” brought about by the end of the “Jap-Russo” War of 1905.

We are told it was an “inside job”.

Somehow Teddy Roosevelt gets involved with Kaiser Wilhelm in arranging for the Russians to pay indemnity to the Japanese in terms of a land agreement of Southern Manchuria, opening the way to exploitation of China by the Japanese. Something else happens, the South Manchuria Railroad gets thrown in as well as four competing U.S. banks and Elihu Root and a failed League of Nations agreement which upsets a balance of power and brings “the Astors, Canterbury and the Guggenheims” into competition with the Japanese and Kaiser Wilhelm, doing something to the Treaty of Washington.

After this incredible and unconnected and partially non-existent series of events is both untangled and entangled before our eyes, the writer reaches the lonely and very solitary conclusion that “the necessary documents to prove these charges (??) could be secured through the kidnapping of the Lindbergh baby”. I was waiting for the author to make a case for Lindbergh's real-life (and long held) Nazi sympathies, but that just didn't happen.

I really have no idea of what the writer is talking about, but the failure of making any connection whatsoever with any of the “facts and circumstances” is magnificently appalling, and has moved itself from the realm of being so bad that it isn’t even “bad” anymore. It is that singular sort of “badness” that makes the printed words seep into the paper and disappear before your very eyes, and the only thing that you can say is "wow".

Posted by John F. Ptak in Absurdist, Unintentional, Bad Ideas, Outsider Logic | Permalink | Comments (0) | TrackBack (0)

Tags: Lindbergh, Lindbergh kidnapping, outsider logic

JF Ptak Science Books Post 1194

[These images are all available for purchase from our blog bookstore, here.]

(1) The Composition of Relief and Happiness--Minus One. Free France, 1918.

This remarkable photograph shows the joy and relief of the townspeople of Saudemont, France (20 kilometers south-east of Arras), after just having been freed from German occupation after four years of captivity.

Saudemont had evidently suffered greatly over the four years, and seemed as though the population of the entire town was going ot be removed along with the Germans--but they weren't, and teh town was simply abandoned, found and recaptured by these Canadian forces.

The images of overwhelming joy are (almost) everywhere:

Except of course for the man at the fulcrum of the image (and the woman behind him), who remained, well, stolid:

But so far as everyone else is concerned:

(2) In this second photograph, taken of American troops at a ceremony at the cemetery of St. Marie, Havre, France in November 1918, the massive crowd (the largest funeral service held in France) is almost entirely focused on the proceedings--except this one serviceman in front, lathced onto the photographer.

(3)

Another extraordinary image of pressed-together humans, of a human sea, a carpet of hatted men. And believe me, every person in this image of (I'd say) approximately 5000 men has got a hat on. There are hundreds of folks in the photo who re aware of the photographer and who are looking right at the camera, but there is only *one* person who is lifting his hat to the photographer.

Another extraordinary image of pressed-together humans, of a human sea, a carpet of hatted men. And believe me, every person in this image of (I'd say) approximately 5000 men has got a hat on. There are hundreds of folks in the photo who re aware of the photographer and who are looking right at the camera, but there is only *one* person who is lifting his hat to the photographer.

Posted by John F. Ptak in Absurdist, Unintentional, Militaria, Photography, World War I | Permalink | Comments (0) | TrackBack (0)