JF Ptak Science Books Post 1944

The idea of the mastery of nature presents itself at different levels at different times, and the mid-Victorian Brits had a particular and interesting handle on the issue int he mid-late 19th century.

Mr. Darwin created a new threshold for the deep understanding of Nature and the possibilities of what that knowledge base might mean for generations to come--it was in a sense a time machine of possibility.

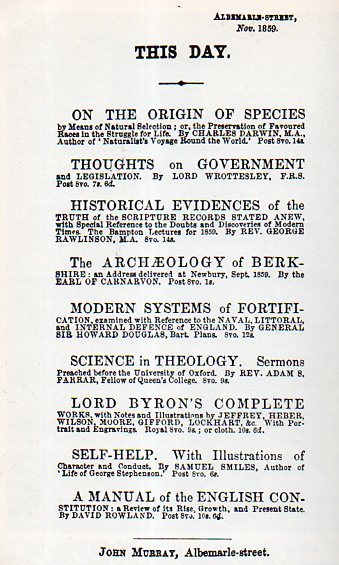

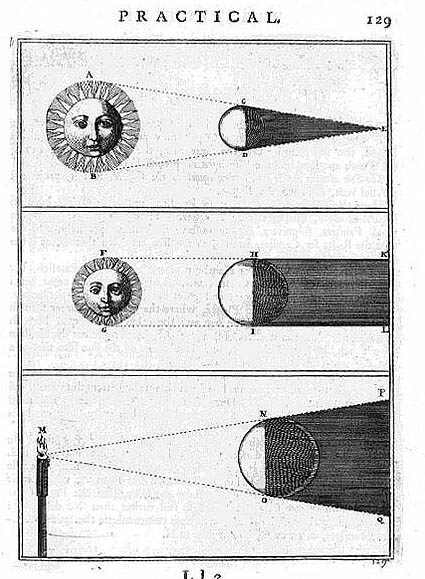

It is thrilling to see this announcement from Darwin's publisher, John Murray (London), leading off On the Origin of Species in their list of nine new books appearing in their new books list for 26 November 1859 in the journal The Athenaeum.. Most of the other books have slipped into dusty bits, though, remarkably, a few are still around. One of them is coyly significant, and its author is important for yet another reason. The book is number eight on this list: Samuel Smiles Self-Help1, which was about the first book of its kind, a homily to honest work and insight and mutual benefit--it also outsold the Origin, with 20,000 sales in the first year, a bona fide bestseller. (The book would sell a quarter of a million copies by the time of Victoria's death.) So in its way, this book too helped people master another sort of nature--their own.

It is thrilling to see this announcement from Darwin's publisher, John Murray (London), leading off On the Origin of Species in their list of nine new books appearing in their new books list for 26 November 1859 in the journal The Athenaeum.. Most of the other books have slipped into dusty bits, though, remarkably, a few are still around. One of them is coyly significant, and its author is important for yet another reason. The book is number eight on this list: Samuel Smiles Self-Help1, which was about the first book of its kind, a homily to honest work and insight and mutual benefit--it also outsold the Origin, with 20,000 sales in the first year, a bona fide bestseller. (The book would sell a quarter of a million copies by the time of Victoria's death.) So in its way, this book too helped people master another sort of nature--their own.

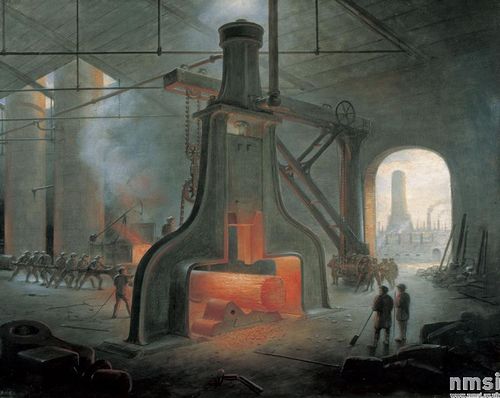

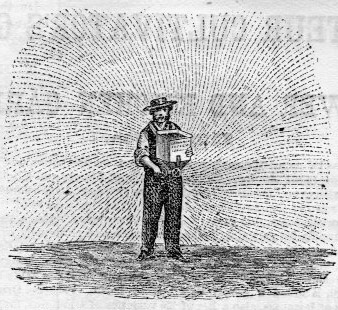

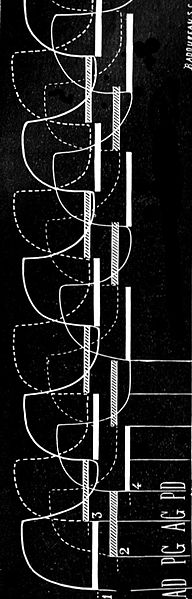

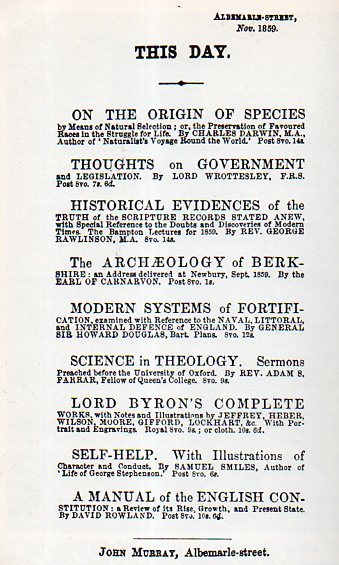

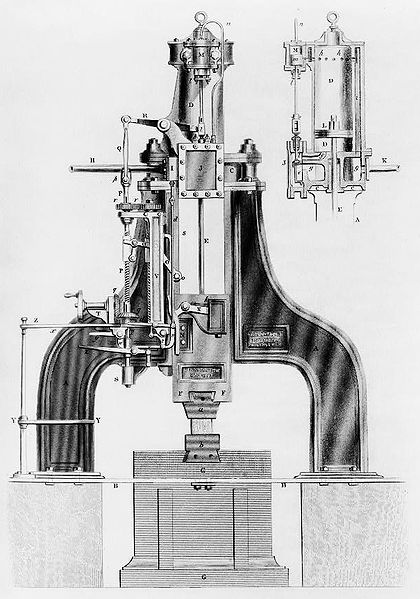

But that is not why we're visiting with Mr. Smiles--I'm more interested in his description of an element of British technology that was a wonder of its age: the powerful industrial hammer of James Nasmyth2. It was a technological achievement of the highest order and something that seems difficult to appreciate today. Invented in 1839 (the year of the invention of photography and the publication of Darwin's report from his researches on board the Beagle) a more massively-powerful version was displayed at the Great Exhibition of 1851, and was its star performer.

[Image source and notes: see Note #4 below]

[Image source and notes: see Note #4 below]

Smiles' made a very interesting observation on the nature of power the machine--rather on its power and the control of its power. The often-told story is that in demonstrating the device Nasmyth would explain and at times demonstrate the capacity of teh hammer to work on large elements going into huge ships; he would also explain that this vast power was also finely tuned and controllable and show this to be the case by having it crack an egg that was in a wine glass without damaging the glass. This meant that aside from being able to handle metals almost as thick as a person, it could also be relied upon to do extremely delicate work, and that the tens of thousands of pounds of pressure it could exert could be called upon to do even the most delicate task. This was a fantastic triumph of control, and was a keen insight into the coming nature of the machine and the rest of the developing Industrial Revolution.

.

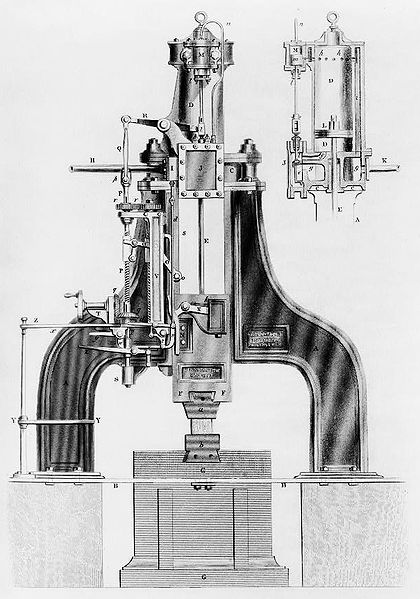

The post-Exhibition of a smaller variation of the hammer, about 12' tall, from Cyclopædia of useful arts, mechanical and

chemical, manufactures, mining, and engineering, ed. by Charles

Tomlinson, London : New York, G. Virtue & co., 1854.

The post-Exhibition of a smaller variation of the hammer, about 12' tall, from Cyclopædia of useful arts, mechanical and

chemical, manufactures, mining, and engineering, ed. by Charles

Tomlinson, London : New York, G. Virtue & co., 1854.

Notes

1. The book (the full text available here) is introduced with the following two quotes from Mill and Disraeli:

“The worth of a State, in the long run, is the worth of the

individuals composing it.”—J. S. Mill.

“We put too much faith in systems, and look too little to men.”—B.

Disraeli.

Self Help ends with this quote from Francis Drake: