JF Ptak Science Books LLC Post 1018

“It is probably not worth putting (all) railways under ground.” Ed Teller, 1947

[See also our 50+-part Atomic & Nuclear Bomb series here]

There is a universe of alternate universes constructed of nothing but the dim bits of bad thinking that is the very DNA of the history of bad ideas. In those realms there are bad ideas that are bad, bad ideas that are toweringly bad, and bad ideas that are so bad that they’re not even bad as they transcend communication capacities of badness. The idea I’m writing about today lives at that unspeakably-bad level.

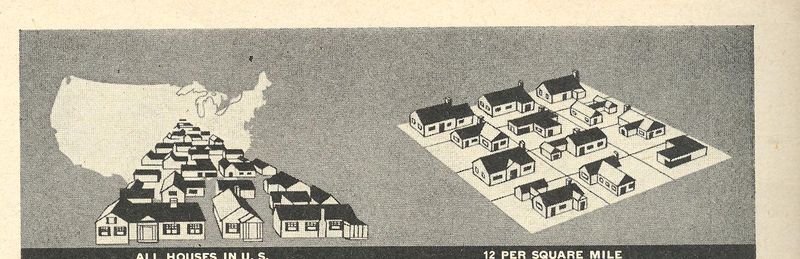

And that bad idea is this: relocating and dispersing the entire population of the United States into a geometric grid-work covering all parts of the country, emptying all American cities into a vast nothingness of exurban Atomburbs.

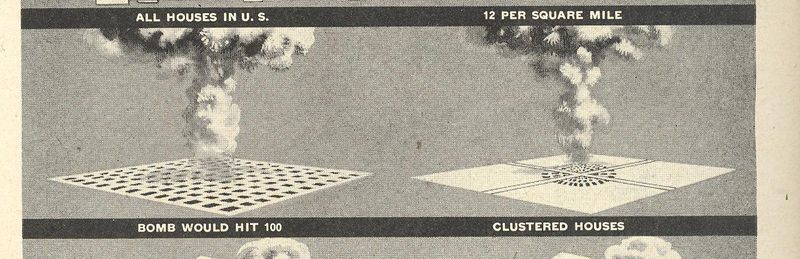

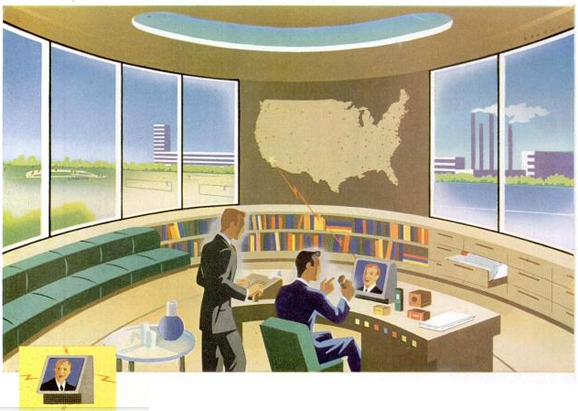

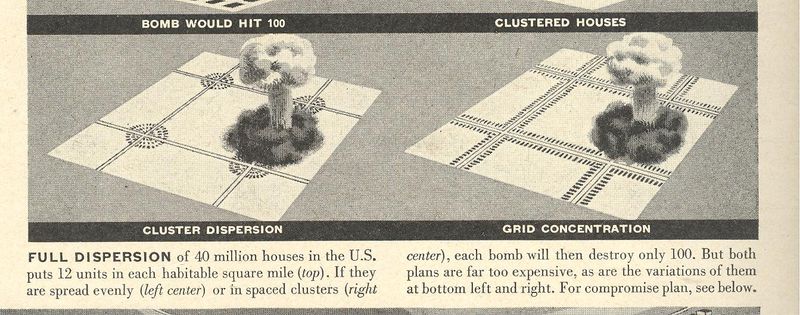

There. I said it. Unfortunately, the thoughtfully blank idea was “real” and was worked out by three smart guys, the result published in the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists in 19461. The kernel of the proposition was republished for the masses in LIFE magazine in (15 June) 1947, complete with maps which stand on their own as being spectacular and peculiar examples of visual propaganda.

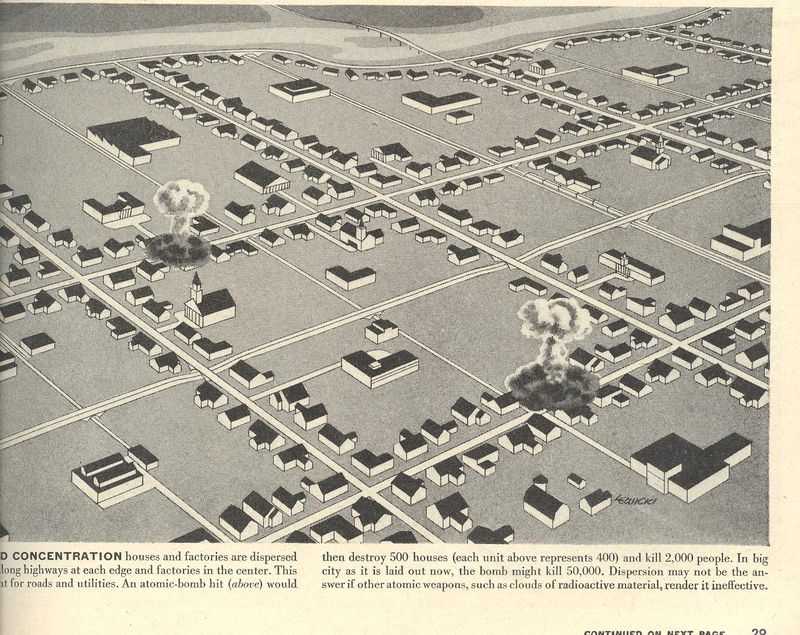

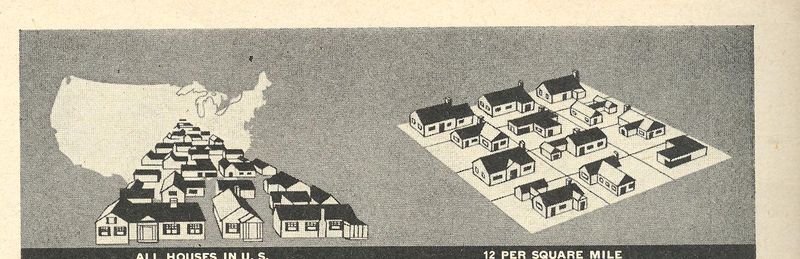

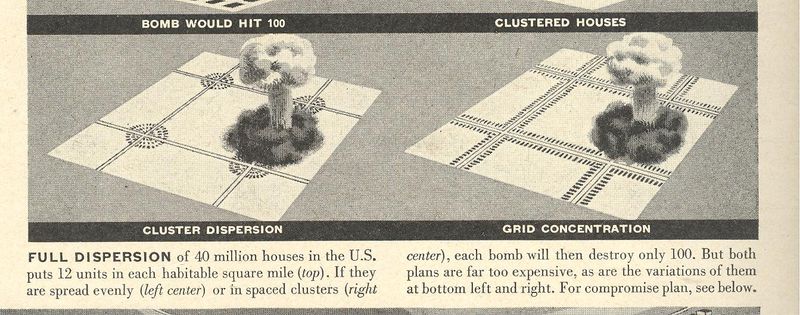

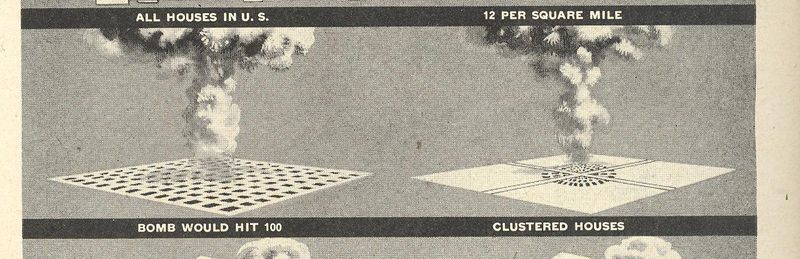

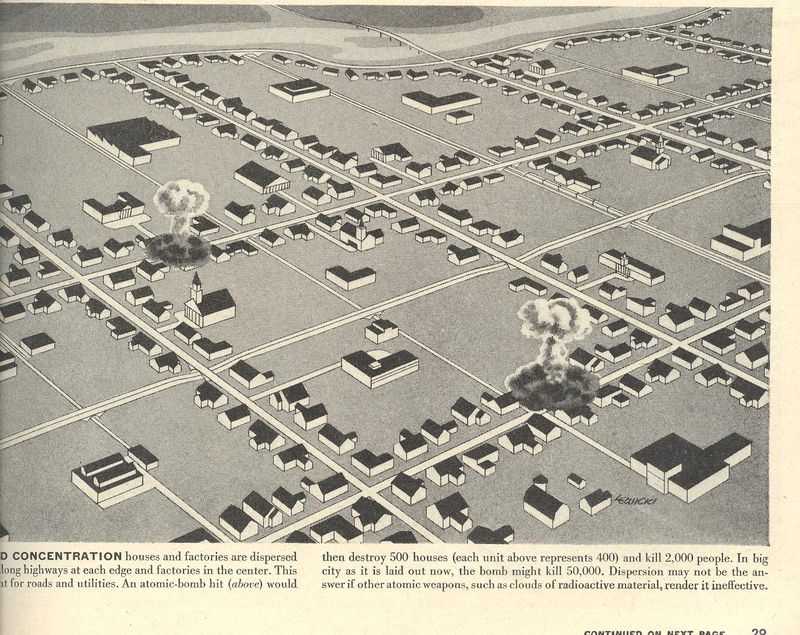

Listen: the crux of the issue was to remove everyone from any American city with a population greater than 50,000 people and place them in newly-built communities set out across the country’s landscape (mostly) like a chess board, the towns existing on all of the connecting lines. [As weird as this sounds, the great Norbert Wiener came up with a similarly astounding, untouchable idea using circles.]. The authors proposed to build 20,000,000 new homes, relocate industry (preferably underground), reallocate and redistribute energy supplies and natural resources, and recreate the very fabric of social and economic life in America.

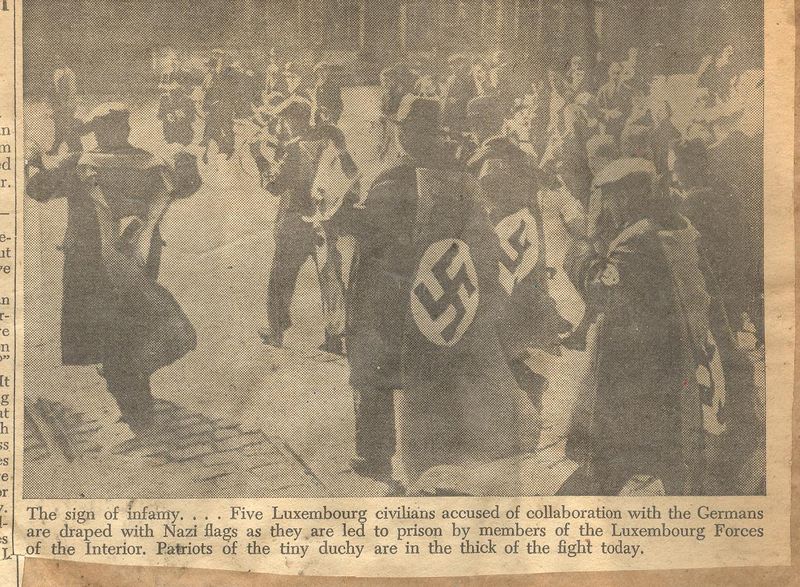

The governor of this thinking was the coming arms race and the American susceptibility to clouds laced with Soviet atomic weapons–and worse.[The calculations for destruction being used here were for the Hiroshima atomic bomb; in 1952 the U.S. would detonate the first hydrogen bomb, followed by the Soviets the next year. These bombs would be measuring explosive force in terms of hundreds of thousands--and then dozens of millions--of pounds of explosives.] How does this idea get thunk in a group and not abandoned? And then how does it manage to be published by a a reputable organization? These are smart men, these authors, and I just cannot think of how they could’ve come to these conclusions–though Teller, who was part of the genius flotilla of superb and essential Hungarian scientists, was undoubtedly mentally affected by his supernova hawkishness. I didn’t know this about Marshak, and I really am not very familiar with Klein. They were all University of Chicago, and the Bulletin was originally published as the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists of Chicago.

There are deeper, more disturbingly anti-spectacular ideas laced through the short article, some of which are so soaringly and diligently insane that it is difficult to address them. For example, the authors suggest that the “ribbon cities” wouldn’t necessarily have to be “laid out in exactly straight lines” and that the lines could be adapted to the terrain.

Even though the authors propose moving and rehousing 20 million people (and so on), this was not what they really wanted to do.

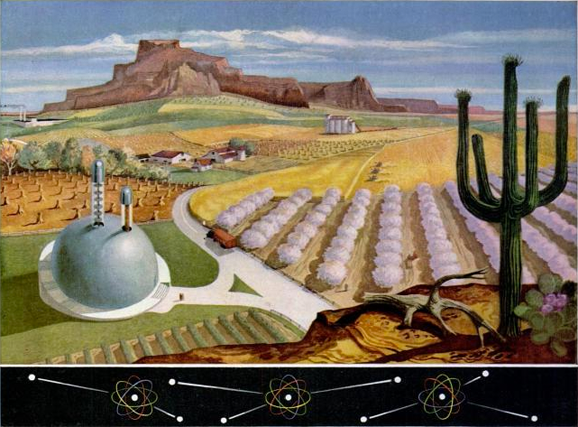

They wanted to put everything in lines and underground.

“We shall have to forgo elaborate schemes of underground cities” because of expense, they write. And what of the cost, as long as we’re at it? Somehow a figure of 200 billion is floated around–200b in 1947 dollars, which is 5 trillion in 2010 dollars (or so), which really doesn’t seem to be a figure that is in any way near to what an undertaking of this magnitude would cost. (The odd thing about this figure is that $200 billion is about the same percentage for a single year of 1950 GDP as the $5 trillion is of the 2010 GDP.) [It seems unfair to take things out of context like this, but, well, it isn't--the entire article is filled with almost nothing but these statements. In a way I'm doing the authors a service by taking things out of context so that the entirety of their madness isn't revealed as the ugly road-kill thinking it is.]

Of course, g_d knows where all of this building material was going to come from. Or the people who would actually do the work. Were there 3 million construction/building folks in the 1950 census? I don’t think so.

And so in spite of the overwhelmingly underestimated cost, and the rerouting of the infrastructure of the entire country, and moving everyone in the country, and building 20 million houses, and finding the material to do so, and finding the workers to build them all and reconstruct all of the infrastructure and build all industry underground and have the tools to do it all with, the authors felt as though the whole thing could be pulled off in 10 years.

Someone, somewhere, was certainly going to be working late.

And so the interesting part of this thought-tragedy for me is–what is the equivalent idea of this going on right now? I know there is one, and there will be a new one tomorrow.

Notes

1.. Jacob Marshak, Edward Teller, and Lawrence R. Klein. “Dispersal of Cities and Industries.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 1, April 15, 1946, 13.

See also:

“Naked City.” Time. Nov. 28, 1949, 66. Also at. Also see .The City Under the Bomb.. Time, Oct. 12, 1950

Charles Grutzner. “City folks‘ fear of bombs aids boom in rural realty.. “ New York Times. August 27, 1950, 1.

Michael Ray Fitzgerald. Sitcoms and Suburbia. The Role of Network Television in the Deurbanization of the U.S., 1949-1991.

Molella, Arthur P. "The City as Communications Net: Norbert Wiener, the Atomic Bomb, and Urban Dispersal" Technology and Culture - Volume 45, Number 4, October 2004, pp. 764-777