JF Ptak Science Books LLC Post 894

My wise friend Jeff Donlan wrote me the other day about

being momentarily stopped in his tracks on hearing a friend saying that they

were reading their (news)paper on a kindle. Being a bookman and a librarian, his

mind’s eyebrows were raised at the irony of the digital “paper”, and then

pressed on. Kindle may well be on its

way to transforming our concept of the “paper” part of “newspaper” and paper

–printed books in general, and again may be the biggest leap in the

transformation of the distribution of knowledge since the beginnings of the

mass popularization of the internet. I wonder if kindle-esque innovations will

put and keep the word “paper” in quotation marks (or in a Maris-like asterisk*)

and place paper-based info distribution into the antiquarian’s domain. Seems that this is the natural order, a steady progression,

to make communication among our kind simpler—and if not more simple, then

providing more data with greater ease than previously imagined. And I’m not talking here about discussing some

sort of massive abecedary, working from Ugaritic proto-Canannite pre-Phoenician

pre-Greek- alphabet and so on; just an outline of the major deals: moving from spoken word like Thucydides

oceanic memorization and recitation of the Greek cultural cornerstones of the Iliad and Odyssey) to dramatic traditions to written stories to Medieval

copyists to woodblock printing to movable type1 to, well, what, the

internet? And then to kindle-like

machines?

But before the modern kindle there was perhaps a kindle-like

precursor that snakes its way in history to (at least) the very capable hands

of Thomas Edison, who in a furious few years in the mid 1870’s2 invented the

light bulb and the phonograph3 (the later coming as a direct byproduct on work

done on the telephone and telegraph).. He celebrates his phonograph in the North American Review (May 1878)4 and

then lists what he saw as the readymade faits

acomplis of the phonograph, the first of which was weirdly/spectacularly

worded: “1. The captivity of all manner

of sound-waves heretofore designated as fugitive, and their permanent

retention.” Do you hear a soundtrack

with that description? I did. He proceeded with less fanfare: “2. Their

reproduction with all their original characteristics at will, without the

presence or consent of the original source, and after the lapse of any period

of time. 3. The transmission of such captive sounds through the ordinary channels of

commercial intercourse and trade in material form, for purposes of communication

or as merchantable goods. 4. Indefinite multiplication and preservation of

such sounds, without regard to the existence or non-existence of the original source. 5. The

captivation of sounds, with or without the knowledge or consent of the source

of their origin.”

But before the modern kindle there was perhaps a kindle-like

precursor that snakes its way in history to (at least) the very capable hands

of Thomas Edison, who in a furious few years in the mid 1870’s2 invented the

light bulb and the phonograph3 (the later coming as a direct byproduct on work

done on the telephone and telegraph).. He celebrates his phonograph in the North American Review (May 1878)4 and

then lists what he saw as the readymade faits

acomplis of the phonograph, the first of which was weirdly/spectacularly

worded: “1. The captivity of all manner

of sound-waves heretofore designated as fugitive, and their permanent

retention.” Do you hear a soundtrack

with that description? I did. He proceeded with less fanfare: “2. Their

reproduction with all their original characteristics at will, without the

presence or consent of the original source, and after the lapse of any period

of time. 3. The transmission of such captive sounds through the ordinary channels of

commercial intercourse and trade in material form, for purposes of communication

or as merchantable goods. 4. Indefinite multiplication and preservation of

such sounds, without regard to the existence or non-existence of the original source. 5. The

captivation of sounds, with or without the knowledge or consent of the source

of their origin.”

Edison then goes on to list what he saw as distinct

“possibilities” for the use of the phonograph in the not-too-distant future.

There are ten major prospects, the “bookish” aspect and the first major assault

on the way we read is listed fourth (though he wasn’t necessarily weighting his

list in any way). Some of the others in

this list (all of which cam to fruition) include: 1.Dictation and letter writing—using the phonograph to

record letters and correspondence, which was baldly aimed at the business and

corporate trade as the machine was relatively difficult to operate and

expensive. 2 Phonographic

“books”. I noticed that that Edison did not

change the word “book” in any way, even though the book is no longer there with

the application of the phonograph, just the read and spoken words. “Books may be read by the charitably-inclined

professional reader, or by such readers especially employed for that purpose,

and the record of such book used in the asylums of the blind, hospitals, the

sick-chamber, or even with great profit and amusement by the lady or gentleman

whose eyes and hands may be otherwise employed; or, again, because of the

greater enjoyment to be had from a book when read by an elocutionist than when

read by the average reader.” 3. Family records. “For the purpose of preserving the sayings,

the voices, and the last words of the dying member of the family [emphasis

mine] as of great men the phonograph will unquestionably outrank the

photograph.”4. Toys: “A doll which

may speak, sing, cry, or laugh, may be safely promised our children for the

Christmas holidays ensuing. Every species of animal or mechanical toy such as

locomotives, etc. may be supplied with their natural and characteristic

sounds.”

Edison

continued, writing on the phonograph’s application for the study of elocution,

speaking clocks, language preservation (as in documentation of the proper way

of speaking a certain language, something that would’ve come in handy in the

spike of disappearing languages at the end of the 19th century),

telephone recorders and pedagogical lessons.

But

this is all a little far afield from the kindle aspect. Is

the development of things like the kindle another step in the metaphorical

development of a technological alphabet?

Like developing an alphabet for a language, where there are a finite

numbers of symbols that elegantly possess the capacity to transmit all of the

words of a spoken language, is there a corollary for something that makes

systemic sense for the technological transmission of knowledge? I guess the

question would be whether the development of the kindle (and so on) provides

another step towards the completeness of what now stands as a chaotic

environment of information and knowledge distribution?=I

don’t think that there is yet a driving, poetic sense to these new

technologies. The new media provide the means to information but not

necessarily the way to it. They also

don’t lend themselves to memorization, which in the old semi-mnemonic days was

a way to not only record info but also to help understand it by enforcing

prolonged exposure and thought. With as

much data that is daily available, perhaps new information is simply filling

memory holes on the vast hole-ridden plane that is the fabric of the new way of

gathering information. I have little

doubt that in the next revolutionary step in this whole process will be more

knowledge-based than suffering under the weight of primitive

search-engine-based data retrieval of today.

I’d say that once the alphabet of technology is more complete, and that

the issues of search, organization, storage and retrieval makes more sense,

that it may well then leave paper behind.

And perhaps after the power and elegance of having a knowledge system

like this that the next giant step would be not having the devices simply with

us, but in us.

Notes

1. It is interesting to note that among the first items

printed on movable type presses were

packs of tarot cards and religious indulgences (get-out-of-hell cards).

2. For an annotated chronology of some of Edison’s

career see HERE.

3.Edison presented his invention at the offices of the Scientific

American in New York City, the magazine reporting the event in

its 22 December 1877 issue:

"Mr. Thomas A. Edison recently came into this office, placed a little

machine on our desk, turned a crank, and the machine inquired as to our

health, asked how we liked the phonograph, informed us that it was very

well, and bid us a cordial good night." Edison

applied for his patent for the highly original invention on 24 December,

receiving it on 19 February 1878 (patent # 200,521). He would soon lose

interest in this invention and move onto other big things (inventing, for

example, the biopolar dynamo in the next year); it would be Emile Berliner

(1851-1929, and who invented the microphone in this same year) to improve

the phonograph and make it more affordable and accessible and increase its

utility immeasurably. 1877 also saw the publication of Rayleigh’s superb Theory of Sound and Boltzmann’s

revision of the second law.

4. Source here.

Of further interest:

For general browsing in 19th century journals see

the invaluable Library of Congress contribution

Rutgers houses the Edison papers here.

"Clocks Which Will Talk: The Wonderful Possibilities of

Edison's Invention." New

York Sun (April 28, 1878). TAEM

25: 173-174.

"The Phonograph and Its Future." Scientific

American Supplement 124 (May 18, 1878): 1973. TAEM 25: 269.

"The Phonograph and Its Future." North

American Review 126 (May-June 1878): 527-536. Reprinted widely. TAEM

25: 198-199.

"To the Editor." New York Tribune (June 8,

1878): 5.

"The Phonograph and Its Future." Telegraphic

Journal 6 (June 15, 1878): 250. TAEM 25: 265.

"To the Editor." New York Tribune (June 27,

1878): 5. Reprinted in Engineering [see below]. Not selected.

and

now to horses underwater. Or sort of.

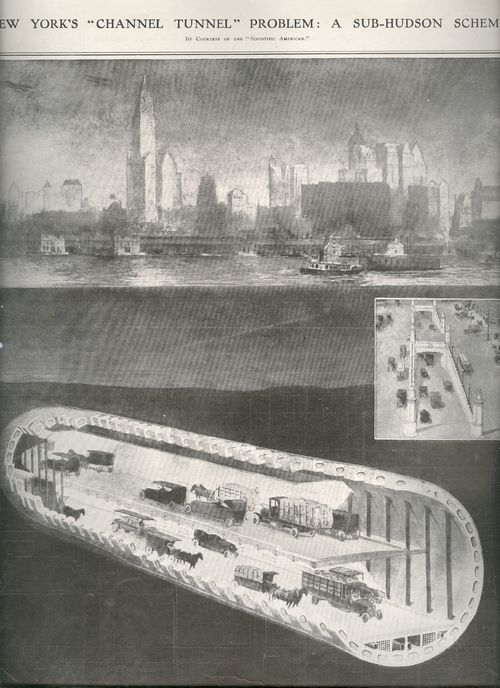

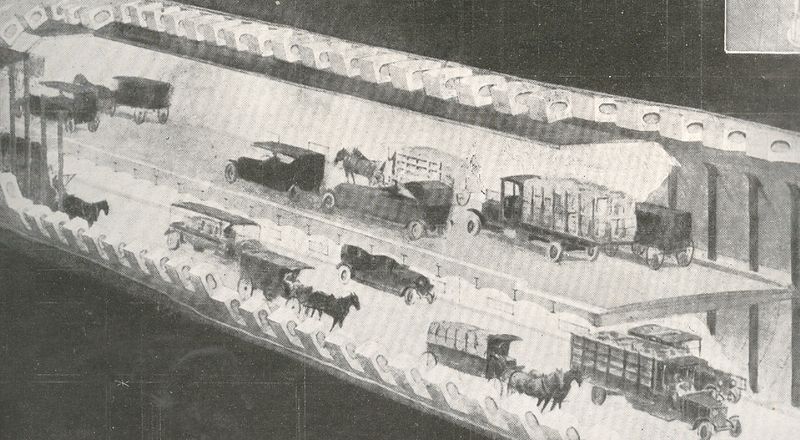

This image from The Illustrated London News (5 April 1919) presents a

cross-section of a proposed Hudson River tunnel connecting the

and

now to horses underwater. Or sort of.

This image from The Illustrated London News (5 April 1919) presents a

cross-section of a proposed Hudson River tunnel connecting the