JF Ptak Science Books LLC Post 669

The great mystery was how those

Indians were smuggled out of the grave, in spite of the watchfulness of those

guards. From the Autobiography of Theodore Edgar

Parker

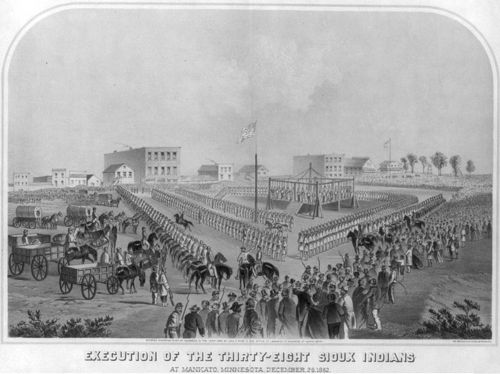

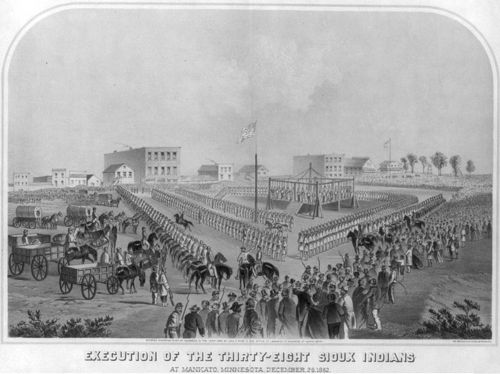

One of the darkest moments of the spectacular Lincoln presidency came on 26 December 1862 when the president chose to not interfere with the vengeful hanging of 38 Santee

Sioux just south of St. Paul, Minnesota. This was the legal outcome of a short-fought “war”(known as "The Great Sioux Uprising", "the Dakota War of 1862" and "Little Crow's War")

fought between U.S. soldiers and several Siouan tribes—a war brought on by the

desperate tribes after suffering failed crops and the reneged treaty obligations

(including a long-overdue payment of $1.4 million for the purchase of 24

million acres, or about a nickel an acre) of their Great Father in D.C. It was really more like a hunting expedition—the

Indians, who had rampaged and taken hostages and so forth, were at the end of

their endurance. The warriors were ill-equipped for almost anything, with little

food and failing horses, and were positively no match for the federal troops who

would hunt them down and destroy them.

“Destroy” isn’t my choice for words—it is used over and over again in the

communications between the field commander General Henry Sibley and the

general in charge of the entire region, General John Pope. It turns out that Pope was of the Tecumseh Sherman

school of Indian relations, writing for the record

"It

is my purpose to utterly exterminate the Sioux. They are to be treated as

maniacs or wild beasts, and by no means as people with whom treaties or compromise

can be made."