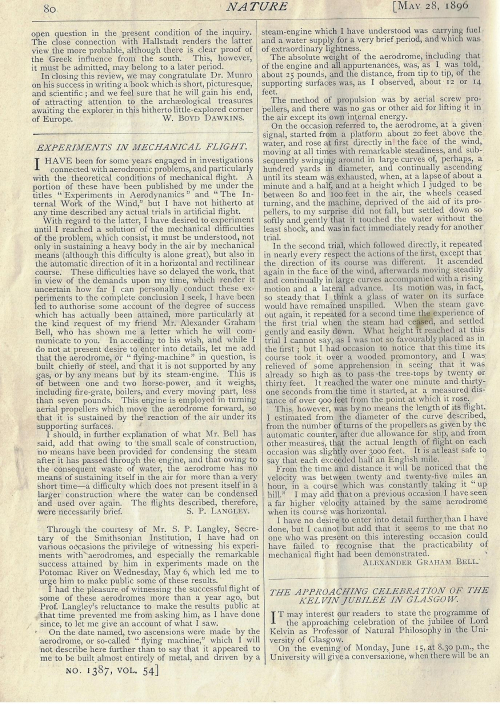

Langley, Samuel Pierpont and Alexander Graham Bell. “Experiments in Mechanical Flight”, in Nature, volume 54, May 28, 1896, page 80 in the issue of pp 73-96. Offered is the weekly issue in the original wrappers (cover plus 3pp of advertisements), removed from a larger bound volume. Provenance: this is a good association copy as it comes from the Langley's own Smithsonian Institutions' Astrophysical Observatory, via the Library of Congress. Condition: there are two vertical pressure marks that run through the volume—they are very light, but they are definitely visible. GOOD+ copy $250

This is the first printing of the famous flight in English in Great Britain and Europe, appearing in Nature, May 28, 1896.

- The first report on the flight seems to have been in Science, May 22, 1896, according to Brockett's Bibliography of Aeronautics, #7160.

- The first report of the flight to appear in Europe appeared two days earlier in Comptes Rendus, vol 122, May 26, 1896, p 1179. The contents of the report is mostly the same, though there are differences, particularly in the second to last paragraph, speaking of the gentleness of the plane gliding after the engine terminated. The last few sentences, with Bell's famous statement, is pretty much the same. (“Il me semble que personne n'aurait pu assister à cet intéressant spectacle sans être convaincu que la possibilité de voler dans l'air à l'aide des moyens mécaniques venait d'être démontrée.”)

I think most people remember Langley as the (Third) Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution and for his work in astrophysics and observational astronomy, but he was a significant figure in the history of aviation, publishing his first extended work in the field in Experiments in Aerodynamics in 1891, and became one of the first if not the first aerodynamics experimenter in the U.S. He was also the first government-sponsored in-house researcher in this field.

I think most people remember Langley as the (Third) Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution and for his work in astrophysics and observational astronomy, but he was a significant figure in the history of aviation, publishing his first extended work in the field in Experiments in Aerodynamics in 1891, and became one of the first if not the first aerodynamics experimenter in the U.S. He was also the first government-sponsored in-house researcher in this field.

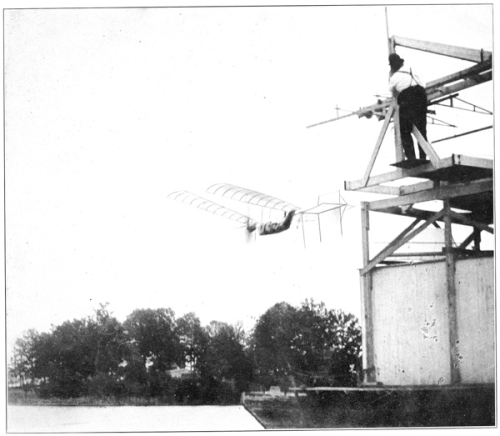

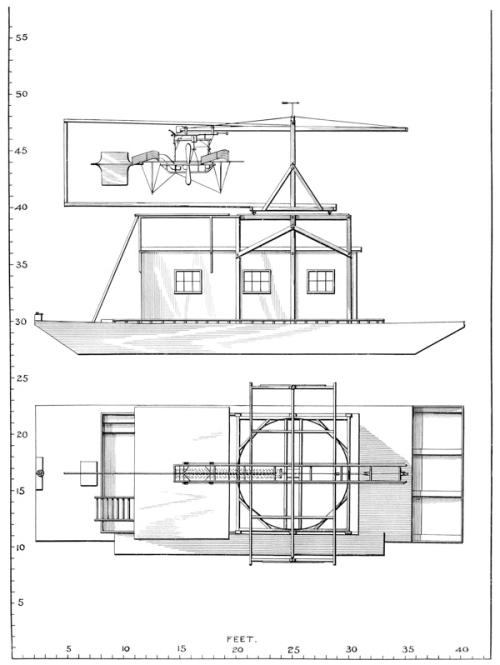

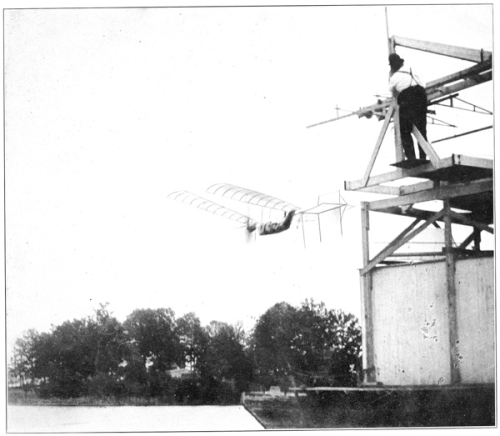

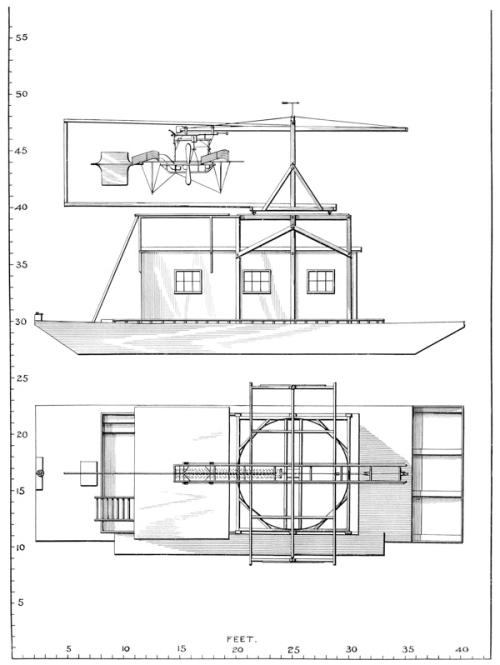

Langley's historic experiments in May 1896 with his 13'-wide Aerodrome 5 took place on a makeshift "houseboat" ("...nothing more than a scow about 30 feet long by 12 feet wide, upon which a small house was erected, to be used for the occasional storing of the aerodromes...”)1 moored in the Potomac River a few miles south of D.C. near Quanitco, Virginia. There was one witness to this affair, Langley being very concerned for privacy, particularly not wanting news of failures to reach a general audience. His guest observer was his old friend, Alexander Graham Bell, who had already witnessed some of Langley's earlier attempts with models and made monetary contributions to help fund the larger enterprises. Langley had no interest in making the report—though he did invite Bell to do so. And it is the second part of this short, two-part paper in which Bell's observations appear.

Langley's own description of the aircraft appeared in his Mechanical Flight2 : "The aerodrome was built chiefly of steel, though lighter material entered into the construction, so that its density as a whole was a little below unity. No gas whatever entered into the construction of the machine, and the absolute weight, independent of fuel and water, was about 11 kilos (24 pounds). The width of the supporting surfaces was about 4 metres (13 feet), and the power was furnished by an extremely light engine of approximately one horse-power. There was no one to direct it on board, and the means for keeping it automatically in horizontal flight were not complete. It is important to remark that the small dimensions of the machine did not allow it to include any apparatus for condensing the steam, so that it could only carry water enough for a very brief course—a drawback which would not be encountered in one of a larger construction.”

Bell's description of the aircraft: “On the date named two ascensions were made by the aerodrome, or so-called “flying machine,” which I will not describe here further than to say that it appeared to me to be built almost entirely of metal, and driven by a steam engine which I have understood was carrying fuel and a water supply for a very brief period, and which was of an extraordinary lightness.” And “The method of propulsion was by aerial screw propellers, and there was no gas or other aid for lifting it in the air except its own internal energy...The absolute weight of the aerodrome, including that of the engine and all appurtenances, was, as I was told, about twenty-five pounds, and the distance from tip to tip of the supporting surfaces was, as I observed, about twelve or fourteen feet3.”

The flying experiment began, and much to the delight of Langley, Bell, and the men who fished previous flying efforts from the Potomac, the two Aerodrome 5 flights for the day were successful. The first flight brought the steam-driven, one-quarter-scale model made a half mile at altitudes of up to 100 feet, marking it the world's first flight of its type. The second flew longer, and faster, and Bell was much impressed by the serenity of the plane's descent once the engine exhausted its fuel, turning the plane into a glider that touched lightly down onto the Potomac.

Bell was thrilled with the display, and recorded what he felt:

- The flying machine "resembled an enormous bird, swooping steadily upward in a spiral path until it reached a height of about 100 feet in the air.”

And then, Bell famously observed:

- “It seems to me that no one who was present on this interesting occasion could have failed to recognize that the practicability of mechanical flight had been demonstrated.”

The once-reticent Langley himself writes an account of the event in “The Flying Machine” in the June 1897 issue of McClure's (vol IX/2)--this was a very public article in a very popular magazine that also featured a drawing of the aerodrome right on the front cover. The article also includes the Bell observations as well as the first printing of the photograph that Bell made of the second flight, the first of its kind, though it is really a drawing after the photograph, the photo itself used as proof of the event and the drawing done to enhance that. The coverage of the event and the Bell statement also appears in the Smithsonian Reports for 1896 (published in 1897). Later, Scientific American Supplement #1404 , Nov 29, 1902, reprints the Bell observations and other historical statements in “The Langley Aerodrome”.

The Aerodrome 5 in flight. Image via Langley's 1911 Experiments...(see below; the image is not in the Nature article)

The Aerodrome 5 in flight. Image via Langley's 1911 Experiments...(see below; the image is not in the Nature article)

Even in the face of support of U.S. presidents and stipends from the military, and with mounting successes, the public failures of his expanded, full-size Aerodrome 6 in 1903 proved to be too much for Langley and his supporters, and he retired from this field. Just two weeks later (December 17) the Wrights made their historic flight at Kitty Hawk--they were successful in many of the ways that Langley was not and made the first manned, powered, controlled, and sustained flight. Early aviation expert Tom Crouch of the National Air and Space Museum remarked that "The problem was the machine itself and Langley's approach...he did just about everything wrong that the Wright brothers did right. “4

That said, John D. Anderson Jr in the AIAA Journal states that it must not be overlooked that “[Langley] made extensive use of aerodynamic coeffcients and legitimately shares with Lilienthal the credit for introducing the concept of lift, drag, and resultant force coeffcients to the applied aerodynamics community. His data are the first substantive proof of the aerodynamic superiority of high-aspect-ratio wings over those with low aspect ratio; it is curious that Langley is not widely recognized for this important contribution." And significantly, “the work did serve a very useful purpose. The fact that a man of Langley’s stature believed in the possibility of the flying machine was enough to convince most laymen that aeronautics was no longer the pastime of fools.”5

NOTES

- Samuel P. Langley and Charles Manly (editor), Langley Memoir in Mechanical Flight, Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge, Washington, D.C., 1911. Part I (Langley), 1887-1896; Part II (Manly), 1897-1903.

- _____. Langley, p. 123.

- From the Nature article, quoted above.

- Lee Wolff, "First in Flight (Almost)", http://www.chopawamsic.com/First%20Flight.htm

- John D. Anderson Jr., “ Langley’s Aeronautical Research: A Modern Critique and Reassessment”, AIAA JOURNAL Vol. 35, No. 3, March 1997 Historical Review Paper.

The extended quote by Bell in the last three paragraphs from the Comptes Rendus:

“La durée du vol, dans le second essai, fut d'une minute et trente-une secondes et la vitesse moyenne entre vingt et vingt-cinq milles à l'heure (soit dix mètres par seconde) sur un trajet qui fut constamment en pente ascendante.”

“Je fus extrêmement frappé du vol aisé et régulier de la machine dans les deux essais, et du fait que lorsque l'appareil, privé de la force motrice de la vapeur au plus haut point de sa course, fut abandonné à lui-même, il descendit chaque fois avec une égalité d'allure qui rendrait tout choc ou tout danger impossibles.”

“Il me semble que personne n'aurait pu assister à cet intéressant spectacle sans être convaincu que la possibilité de voler dans l'air à l'aide de moyens mécaniques venait d'être démontrée. “

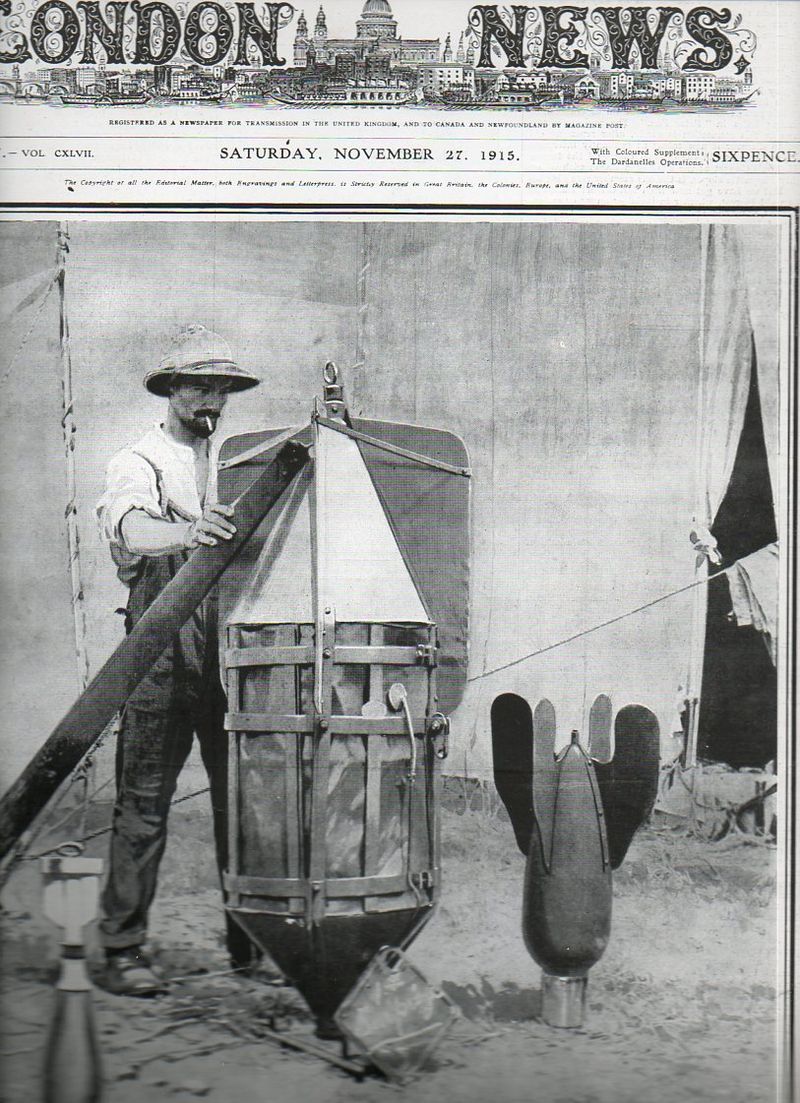

The "hosueboat", with launching apparatus and with the aerodrome in place (from Langley, 1911):

![]() , Paris from 1,800 ft leaves absolutely nothing to be desired. Through a magnifying glass people can be counted on the bridge. The exposure of this and the other photographs taken on this flight was 1/50 second, using a specially constructed guillotine shutter which was opened pneumatically and closed automatically with a rubber spring" (Gernsheim & Gernsheim, The History of Photography 1685-1914 p. 508)--again quoting the very resourceful Mr. Norman (above).

, Paris from 1,800 ft leaves absolutely nothing to be desired. Through a magnifying glass people can be counted on the bridge. The exposure of this and the other photographs taken on this flight was 1/50 second, using a specially constructed guillotine shutter which was opened pneumatically and closed automatically with a rubber spring" (Gernsheim & Gernsheim, The History of Photography 1685-1914 p. 508)--again quoting the very resourceful Mr. Norman (above).